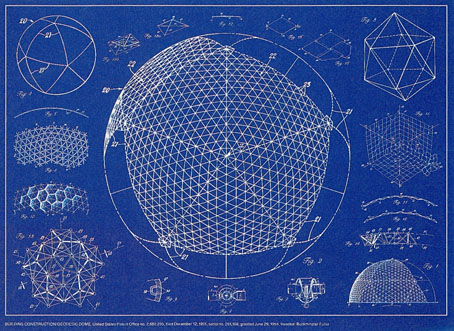

A blueprint by Buckminster Fuller for the first geodesic dome.

• “That opening sequence on the train, it’s got the dynamic of a wonderful pop video. It’s one of the world’s greatest actors who understood the power of small gestures.” Jah Wobble enthusing about Roy Budd, Michael Caine, and Mike Hodges’ baleful revenge drama, Get Carter.

• One of the BFI’s Halloween releases this year will be The Ballad of Tam Lin (1971), the blu-ray debut of a cult film that blends folk horror with modish melodrama. Direction by Roddy McDowall, music by Pentangle, and a cast that includes Ava Gardner and Ian McShane.

• New from A Year In The Country: Cathode Ray And Celluloid Hinterlands, a book exploring weird film and TV, not all of which is from the over-ploughed folk-horror furrows.

The whole notion of the Diggers kind of evolved out of the anarchism thing. And also there was more than a little social conscience. Because, by now, in ‘66, people started to come to the Haight Ashbury from all over. And that was when, in ‘66, it was still, really… Before the “Summer of Love,” it really was the Summer of Love. The “Summer of Love” [in 1967] was Life Magazine’s version. That’s what created the homeless on the streets and all that shit, because so many people came with absolutely no understanding of what they were about.

The role of the Diggers in this period was an outlaw, romantic, feed-the-people, anarchist, ‘Who’s in charge?—YOU ARE’, that kind of thing. That line in Apocalypse Now when he gets to the bridge and the little string of Christmas lights are hanging and he gets to one guy who’s guarding one end of the bridge and he says, Who’s in charge here? He says, I thought you were. And that’s so true. That is so true. Then Grogan, whenever anyone would ask, where’s Emmett Grogan… anyone could say “I’m Emmett Grogan.” So you could deflect a lot of shit.

Harvey Korspan of the San Francisco Diggers talking to Jay Babcock in another installment of Jay’s verbal history of the hippie anarchists

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…Harry Mathews Tlooth (1966).

• Mix of the week: A mix for The Wire by Cheri Knight.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Bangel.

• Tam Lin (1969) by Fairport Convention | Young Tambling (1971) by Anne Briggs | Tamlane (2016) by Dylan Carlson & Coleman Grey