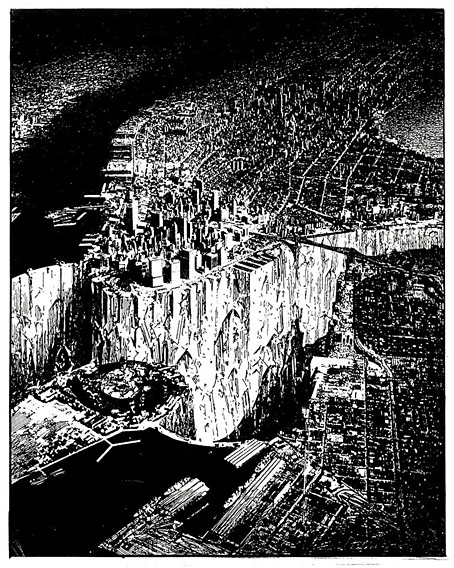

Lower Manhattan (1999) by Lebbeus Woods.

RIP Lebbeus Woods, an architect and illustrator frequently compared to Piranesi not only for his imagination and the quality of his renderings but also for the way both men built very little from a lifetime of designs. Lots of appreciations have appeared over the past few days including this lengthy piece by Geoff Manaugh at BLDGBLOG. (Geoff interviewed Woods in 2007.) Elsewhere: A slideshow at the NYT, Steven Holl remembers Lebbeus Woods and Lebbeus Woods, visionary architect of imaginary worlds. See also: Lebbeus Woods: Early Drawings and this post about Woods’ illustrations for an Arthur C Clarke story collection. Woods was at his most Piranesian with Gothic designs for an artificial planet that would have been the principal location in Vincent Ward’s unmade Alien 3.

• Arkhonia draws to the end of a year of blogging about and around the Beach Boys’ errant masterwork, Smile (1967). Witty, discursive and frequently scabrous accounts of how Brian Wilson’s magnum opus was derailed and marginalised until it became convenient for commercial interests to exploit its reputation. Anyone following those posts won’t have been surprised by Wilson’s sacking from his own group by Mike Love in September.

• “We’ve been underground for 27 hours now. Everyone is caked in mud, with grit in their hair.” Will Hunt explores the catacombs and sewers of Paris.

I think the only remotely interesting drug was acid. I had a slightly peculiar attitude towards it I think. Just about everything about hippydom I hated. I liked the 60s up to about ’65 or ’66. I liked the mod clothes, I liked the look. I wasn’t a keen taker of speed because I didn’t like the comedown from it. Then everything changed and became looser, I didn’t like the clothes at all. I felt rather out of step with it. The acid thing was interesting though. I come from Salisbury and from the age of 12 I had a friend who was 30 years older than I was who I saw regularly up until when he died a couple of years ago, whose obituary I wrote in The Times. This man was called Ken James and he was deputy head at the chemical warfare unit at Porton Down [the MOD’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory]. He then became head of the scientific civil service; he was the man who introduced computing into the civil service and he had taken acid as early as 1950. This was long before Aldous Huxley.

Sharp Suits And Sparkle: Jonathan Meades On Acid, Space And Place by John Doran. Marvellous stuff. Meades’ new book is Museum Without Walls.

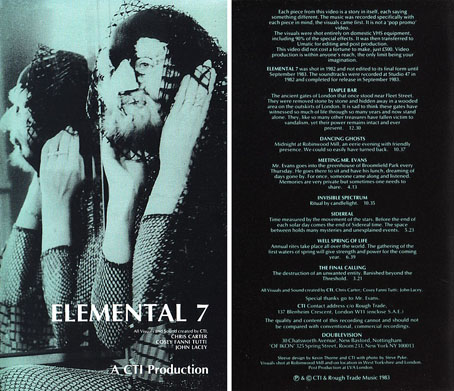

• In New York later this month: A Cathode Ray Séance – The Haunted Worlds of Nigel Kneale.

• More acid: Kerri Smith talks to Oliver Sacks about his drug experiences.

• “It starts with an itch”: Alan Bennett (again) on his new play, People.

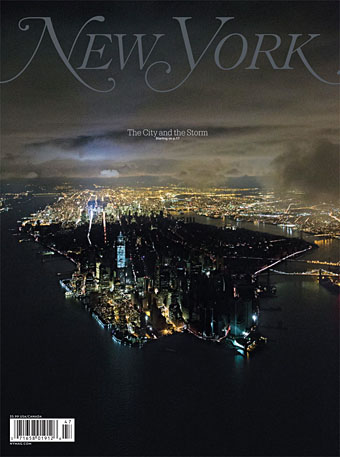

Lower Manhattan last Wednesday. Photo by Iwan Baan.

• Back issues of OMNI magazine can now be found at the Internet Archive.

• Alan Moore & Mitch Jenkins present their new film, Jimmy’s End.

• At BibliOdyssey: Atlas title pages part one & part two.

• Raw Functionality: An interview with Emptyset.

• Stormy Weather (1979) by Elisabeth Welch.