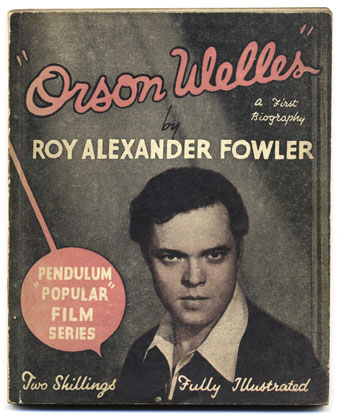

Orson Welles: A First Biography (1946) by Roy Alexander Fowler.

Happy birthday, Orson. The premature celebrity biography is nothing new, as this small volume from the Coulthart library demonstrates. Welles was only 31 in 1946 but was already the director of three feature films. If I’m less of a Welles obsessive today it’s because many of the films and radio plays that were once inaccessible can now be easily seen and heard, although a handful of unfinished projects still wait in the wings. The following is a selection of some favourite Wellesiana, old and new.

• The Mercury Theatre On The Air: Recordings of Welles’ theatre troupe at the Internet Archive and at the dedicated website. The Mercury production of The War of the Worlds is the essential one, of course, but I’m also partial to their production of Dracula which featured Agnes Moorehead playing Mina Harker, Welles as the Count, and a suitably spooky score by Bernard Herrmann. The production of Around the World in 80 Days was later expanded by Welles into an ambitious (and expensive) stage musical in collaboration with Cole Porter.

• The Night America Trembled (1957) is a TV dramatisation of the alarmed reaction of some Americans to the War of the Worlds broadcast. Presented live by Ed Murrow, the drama features Warren Beatty, James Coburn, Warren Oates, and Ed Asner (who later presented the BBC’s RKO Story). Closer to Welles is The Night That Panicked America (1975) a TV movie recreation of the original broadcast with Paul Shenar as the director.

• Newsreel footage of the final scenes of the so-called Voodoo Macbeth from 1936. As part of the WPA program to return Americans to work, Welles directed an all-black cast with the action of the play moved to Haiti. As usual, Welles wasn’t afraid of rearranging the Bard’s words, and this staging ends with the same lines as his 1948 film version: “Peace! The charm’s wound up.”

• My favourite Welles book is still This is Orson Welles (1992), a collection of Peter Bogdanovich’s interviews edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Bogdanovich’s interview tapes can be heard at the Internet Archive.

• Orson Welles’ Horrorshow: Colin Fleming on Welles’ Macbeth, “the horror film no one likes to call a horror film”.

• Peter Bradshaw on Citizen Kane and the meaning of “Rosebud”.

• Six actors who have played Orson Welles onscreen

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Fountain of Youth

• The Complete Citizen Kane

• Return to Glennascaul, a film by Hilton Edwards

• Screening Kafka

• The Panic Broadcast