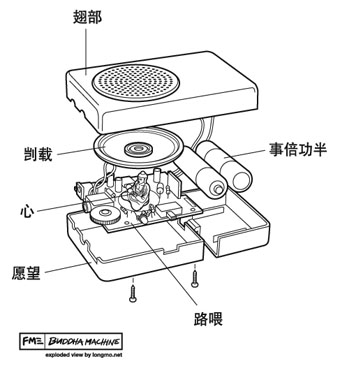

Fm3’s Buddha Machine.

The Electronic Qur’an.

• Compact, robust and easy to use;

• Long lasting battery life;

• Large LCD with blue backlight for night time viewing;

• Built-in audio speaker;

• Built-in DC adapter jack;

• Ability to record up to 3 hours* of voice;

• Follow and compare your own voice with the reciters;

• Excellent sound quality with AudiTrax technology;

• Inter-changeable audio plug-in system;

• Bookmark function;

• Repeat function;

• Search function;

• Full audio recitation;

• Approved/licensed Qur’an text in Arabic (Uthmanic font type);

• Approved/licensed Qur’an text in English (Mushin Khan’s translation);

• Approved Islamic contents in both Arabic and English translation.

Modern Orthodox by Elliott Malkin.

Modern Orthodox is a working demonstration of my next-generation laser eruv system. An eruv (pronounced ey-roov) is a symbolic boundary erected around religious Jewish communities throughout the world. While an eruv is typically constructed with poles and wires, Modern Orthodox employs a combination of low-power lasers, wifi surveillance cameras and graffiti, as a way of designating sacred volumes of space in urban areas.

Crucifix NG by Elliott Malkin.

Crucifix NG (Next Generation) is the principal work of the Faith-Based Electronics Group at the Interactive Televangelist Program (ITP). Crucifix NG is a printed electronic circuit board in the shape of a crucifix. This handheld, wall-mountable device houses a battery-operated transmitter that broadcasts an ASCII, non-denominational version of the Lord’s Prayer at 916 megahertz. (916 has no numerological significance – it is simply a function of the availability of low-cost transmission chips within this FCC license-free bandwidth.)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Layering Buddha by Robert Henke

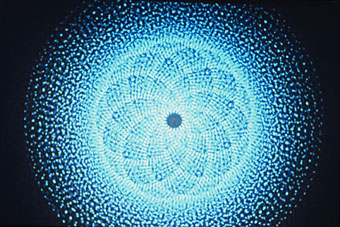

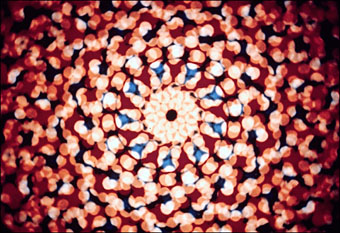

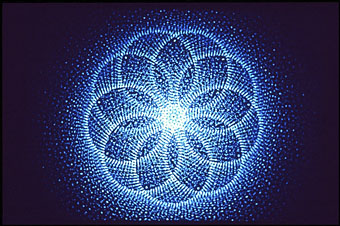

Electric light orchestra

Electric light orchestra