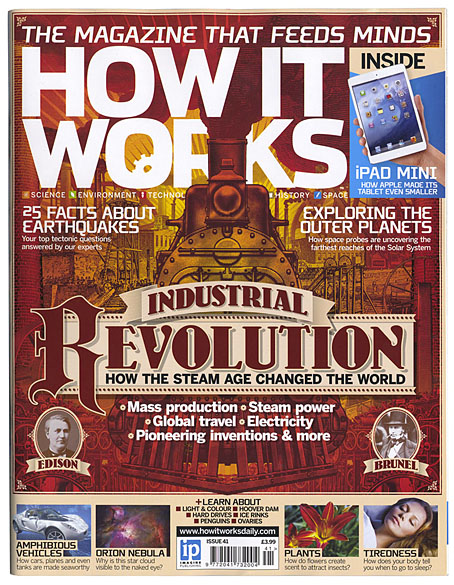

Yes, it’s all happening this month… Unlike other work that’s surfaced recently the cover art for issue 41 of How It Works magazine was completed less than a month ago. Headlines obscure much of the artwork but the picture is also run full-page inside, something I wasn’t expecting. How It Works has major newsstand distribution so people in the UK may see this on shelves in newsagents and supermarkets throughout December.

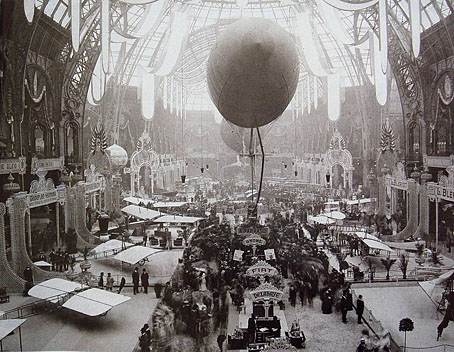

The theme is the Industrial Revolution but the brief was for something similar to a couple of my recent steampunk illustrations, with a request for a colour scheme like that used for the Bookman Histories cover. The main visual requirement was the train looming out of the picture. I thought this wouldn’t be a problem, I have the old Dover Publications’ Transportation book which features many copyright-free engravings of trains, in addition to other books and source material downloaded from the Internet Archive. One of these would be sure to have a decent front elevation of a steam locomotive, right? Wrong. When you start looking for pictures of locomotives you quickly find that 99% of them show the machines from the side or from an angle, as on the Bookman cover. I downloaded three entire books of over 500-pages each from the Internet Archive, fantastic volumes in themselves, especially Modern Locomotive Construction (1892) which contains meticulous descriptions of every last part of a steam locomotive, down to the smallest screw. But none of their drawings were usable.