The Haunted Palace.

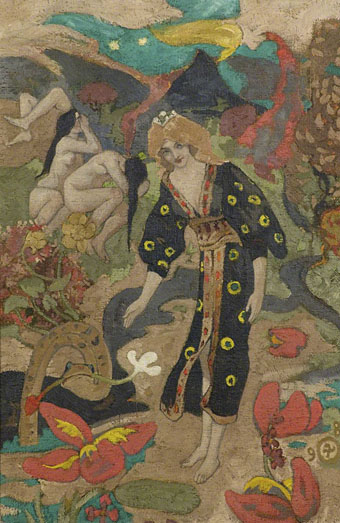

There’s always more Poe. Which means, in the context of these pages, there’s always another illustrated edition to be found. It’s good to finally discover a complete edition of The Bells, and Other Poems; I’d seen a few of these paintings before—Alone was used on the cover of a biography of Poe by Wolf Mankowitz—but the collection tends to be overshadowed by Dulac’s other books. The Internet Archive has had a scan available for several years but most of the colour plates are missing, picture theft being a common hazard for library books. These copies are from a more recent addition to Project Gutenberg.

The Bells.

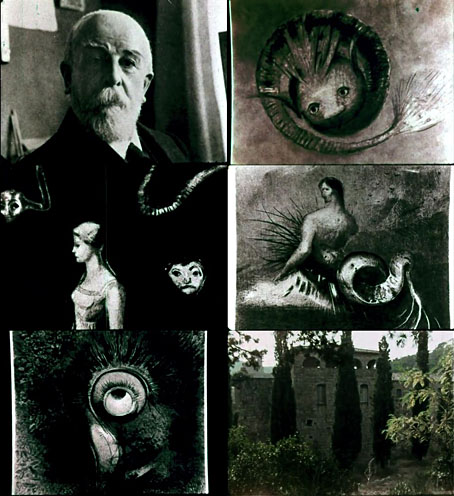

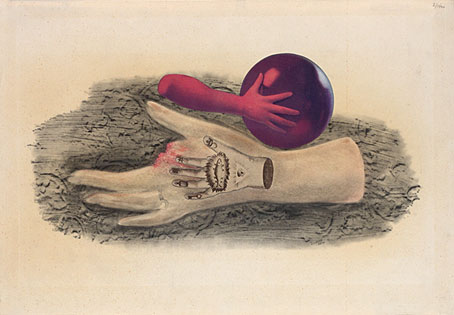

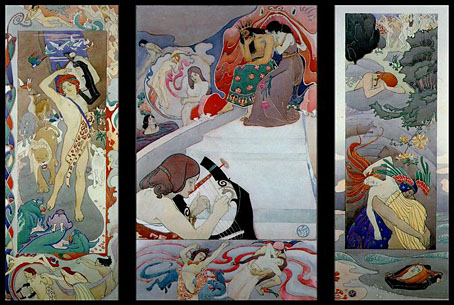

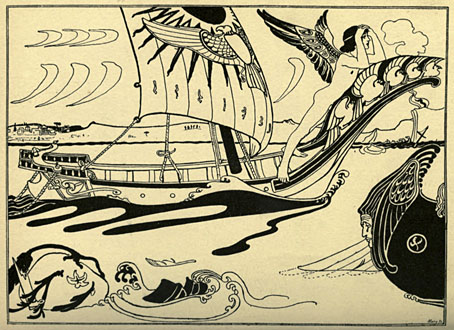

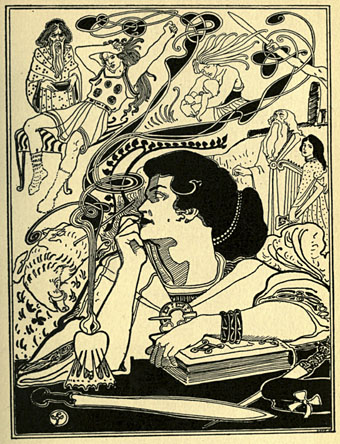

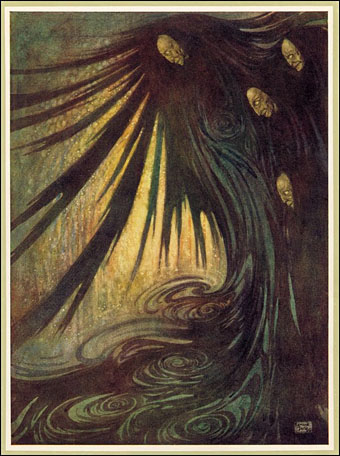

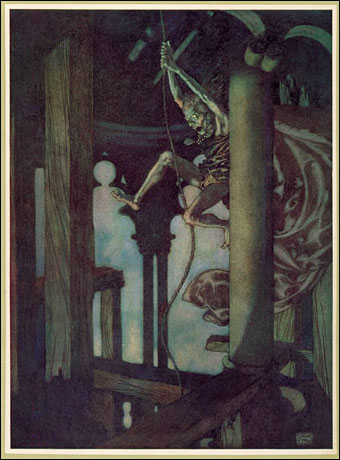

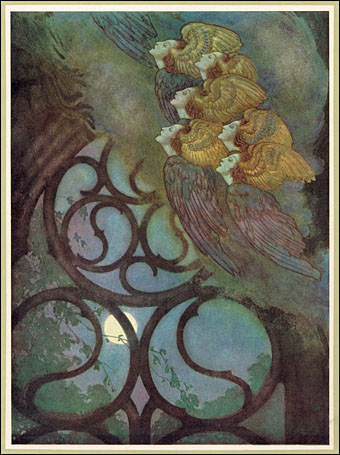

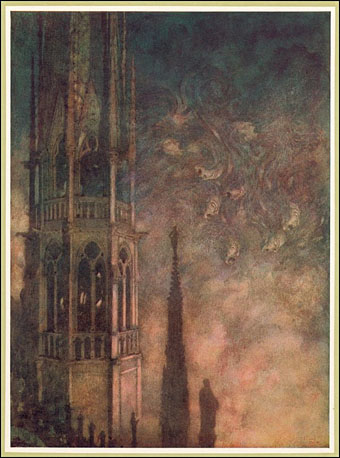

The Bells was published 12 years after W. Heath Robinson had produced his own illustrated edition of Poe poems in 1900. The two books complement each other more than you might expect; all of Robinson’s illustrations are line drawings with an Art Nouveau quality that soon vanished from his work, and was long gone by the time he found a popular audience for his drawings of whimsical inventions. Dulac’s edition includes a few monochrome drawings but these are little more than spot illustrations scattered among the watercolour plates. Several of the paintings, especially the one for Israfel, are Symbolist art as much as they’re illustration. This might seem inevitable given the Symbolist tendencies of Poe’s verse but not all illustrators manage to reflect these qualities.

The Bells.

The Bells.

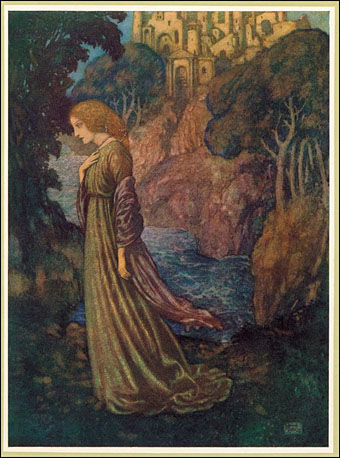

Annabel Lee.