“It had not been able to support the dazzling splendour imposed on it…”

It was a novel without a plot and with only one character, being, indeed, simply a psychological study of a certain young Parisian who spent his life trying to realize in the nineteenth century all the passions and modes of thought that belonged to every century except his own, and to sum up, as it were, in himself the various moods through which the world-spirit had ever passed, loving for their mere artificiality those renunciations that men have unwisely called virtue, as much as those natural rebellions that wise men still call sin. The style in which it was written was that curious jewelled style, vivid and obscure at once, full of argot and of archaisms, of technical expressions and of elaborate paraphrases, that characterizes the work of some of the finest artists of the French school of Symbolistes. There were in it metaphors as monstrous as orchids and as subtle in colour. The life of the senses was described in the terms of mystical philosophy. One hardly knew at times whether one was reading the spiritual ecstasies of some mediaeval saint or the morbid confessions of a modern sinner. It was a poisonous book.

The corrupting French novel which Lord Henry Wotton gives to Dorian Gray is never named by Oscar Wilde but its identity is no secret. À Rebours (Against Nature) by Joris-Karl Huysmans was published in 1884 and Wilde, Whistler and others were immediately impressed by what amounts to a manual for the lifestyle of a Decadent Aesthete. Wilde fell sufficiently under its spell to have Dorian Gray in the later chapters of his own novel indulge his senses much like Huysmans’ protagonist, Des Esseintes; where Des Esseintes grows poisonous blooms and fills his room with exotic perfumes, Dorian Gray luxuriates over a hoard of precious stones.

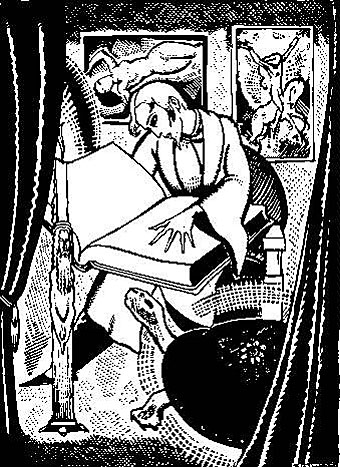

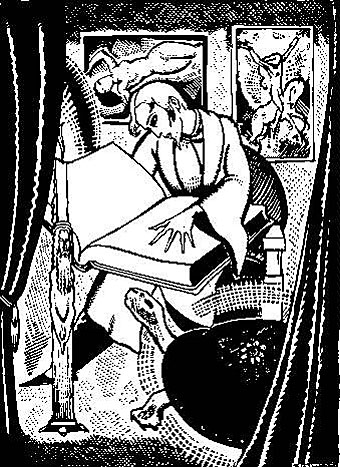

À Rebours features lengthy descriptions of Symbolist art, with particular attention given to Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon. Yet despite the visual description Arthur Zaidenberg’s illustrations are the only ones I’ve come across to date. The book may be influential but it seems too obscure to have attracted illustrators. Zaidenberg’s drawings from a 1931 edition are executed in a woodcut style not far removed from Frans Masereel’s earlier work in books such as Die Stadt (1925), and as such the style is fashionably spare, not necessarily the right choice for a work concerned with sensory delirium. (This Zaidenberg street scene from 1937 shows a definite Masereel influence.) I’d much rather have seen Harry Clarke illustrate Huysmans. Zaidenberg’s drawings are also curious for their foregrounding of the sexual content which makes me think this edition may have been sold on the basis of a salacious reputation. The scene below, for example, doesn’t occur in the novel but can be implied from the description of Des Esseintes meeting a schoolboy in the Avenue de Latour-Maubourg.

“Never had he experienced a more alluring relationship.”

The complete (?) set of Zaidenberg’s illustrations can be seen here. Pages from a later artists’ manual, Anyone Can Draw, are at VTS.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• John Osborne’s Dorian Gray

• Because Wilde’s worth it

• Whistler’s Peacock Room

• Dorian Gray revisited

• Frans Masereel’s city

• The Poet and the Pope

• The Picture of Dorian Gray I & II