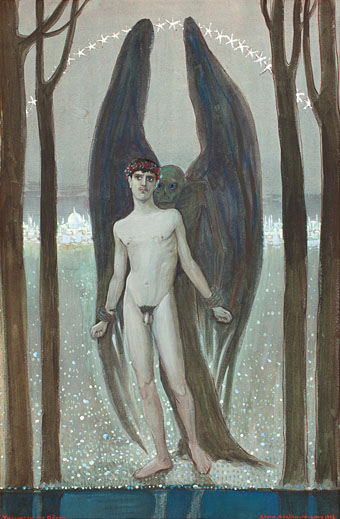

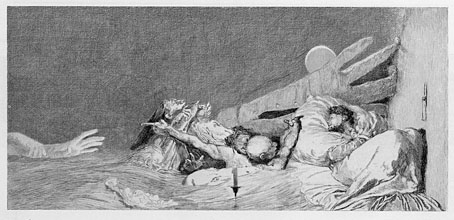

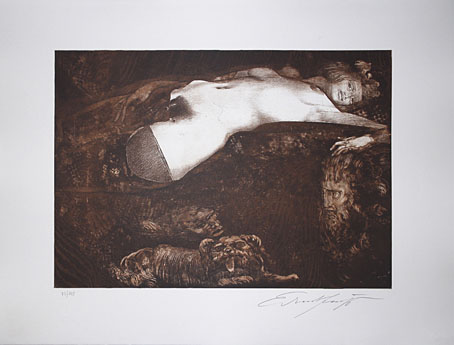

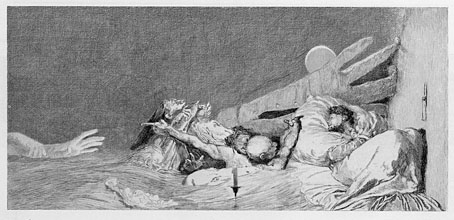

A Glove: Anxieties (1881) by Max Klinger.

Although the Glove‘s scenario was given its due Germanic explication by contemporary critics, it defies rational analysis. The last picture, which was seen as a kind of happy ending to the glove’s peregrinations, is particularly ambiguous and leaves the whole meaning of the series in doubt. The story is a parable of loss based on a trivial lost article, like the lost keys in Bluebeard and in Alice, like Desdemona’s missing handkerchief, or like the philosopher’s spectacles in Klinger’s own Fantasy on Brahms, which have slid out of their proprietor’s reach just as he was nearing the summit of a kind of Matterhorn. There are overtones of erotic symbolism and fetishism in the glove and the phalloid monster who abducts it, heightened for a modern viewer by the Krafft-Ebing period costumes and décors (the engravings appeared in 1881, and the drawings were apparently finished in 1878).

John Ashbery describing Max Klinger’s extraordinary series of etchings A Glove (aka Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove) which in their inexplicable narrative of fetishist obsession anticipate Surrealism. See the entire sequence here or here. For A Glove in print there’s The Graphic Works of Max Klinger from Dover Publications.

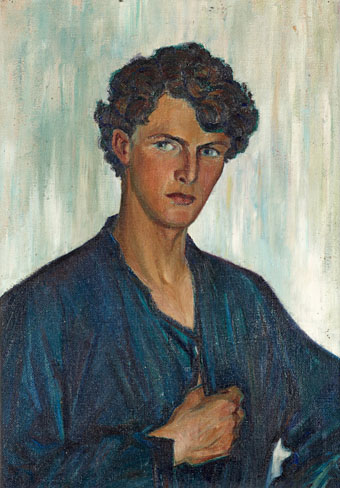

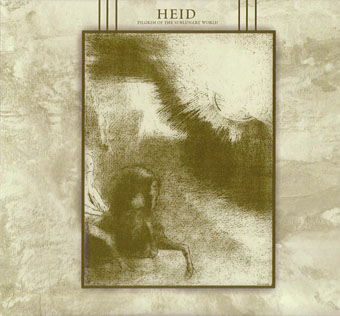

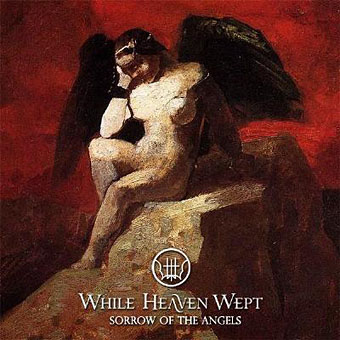

The Song of Love (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico.

Ashbery begins by discussing Giorgio de Chirico’s enthusiasm for Klinger’s work, a passion and influence that provides one of the many connections between the Symbolists and the Surrealists. This “metaphysical” painting looks back to Klinger and forward to Magritte.

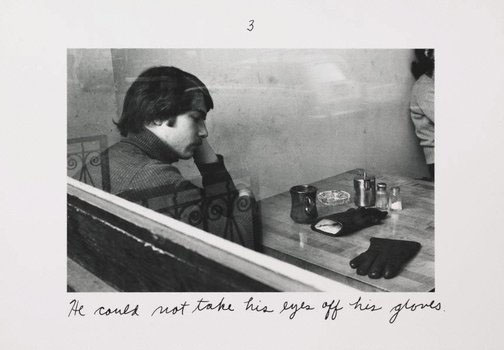

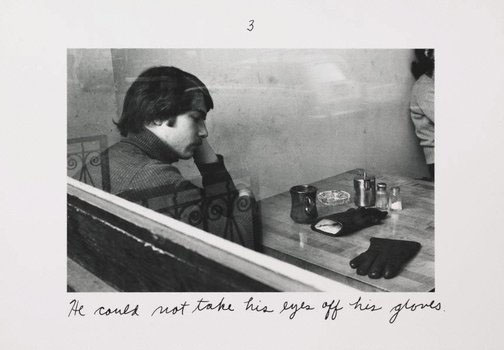

The Pleasures of the Glove, 3 (1974) by Duane Michals.

The enigmatic encounter of ‘The pleasures of the glove’ follows the lead character as he fantasises about a pair of gloves on the hands of a mannequin in a shopfront window. The perverse pleasure of desiring the gloves but not acquiring them leads him on a surreal adventure of first imagining his own glove as a queer furry tunnel that swallows his hand to the fantasy of stroking the naked body of a woman he sees on the bus with her own glove. (more)

A more contemporary take on the same idea, albeit without the intercession of a pterodactyl-like thief. If Klinger is pre-Surrealism then this is the post- version; Michals photographed René Magritte, and many of his other works run in a distinctly Surreal direction. (Thanks to Anne Billson for the tip!)

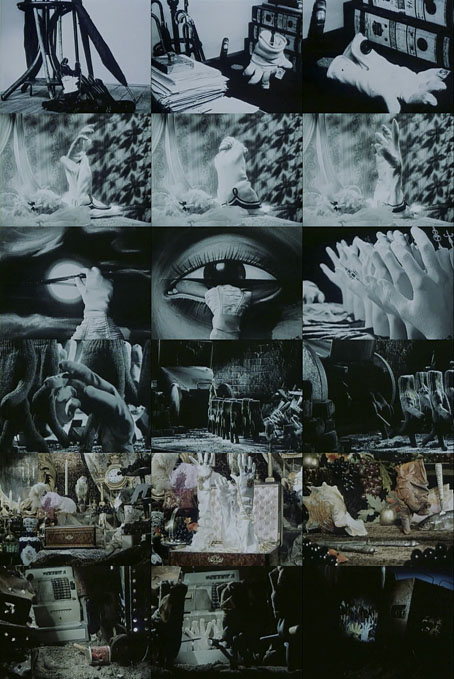

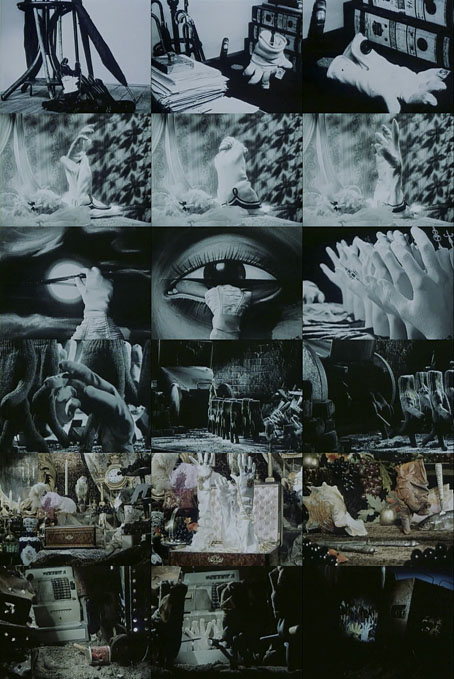

The Vanished World of Gloves (1982) by Czech animator Jiri Barta features sex, Surrealism and a lot more besides, all in the space of 16 minutes. A can of film is unearthed which contains a series of short episodes pastiching different cinematic styles: Chaplinesque slapstick, swashbuckling romance, Buñuel Surrealism, a war film, a Fellini orgy and a science fiction apocalypse. All the parts are played by gloves, of course, and if you didn’t see the credits you might take this at first for a Svankmajer short.

The Vanished World of Gloves: part one | part two

Update: I knew I’d forgotten something… Added de Chirico’s The Song of Love.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More Golems

• Max Klinger’s New Salomé

• Barta’s Golem