The Sin (1894).

Some pictures in honour of the Chinese year of the Water Snake which begins this Sunday. Paintings of women with snakes are legion, even after you winnow out all the Eve and the Serpent pictures, so you need to narrow the field of view. Artists of the 19th century must have been delighted when Gustave Flaubert published Salammbô in 1862, chapter 10 of which—The Serpent—gave them an excuse to depict an exotic woman involved with a snake completely free of any Biblical trappings.

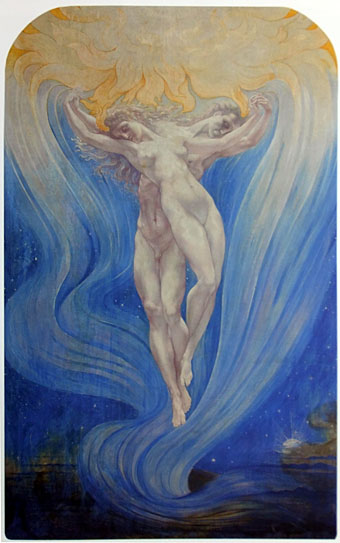

Sensuality (1891).

Franz Stuck’s celebrated trio of serpent women can be read as Eve figures but their provocative posing is more in line with the prurient misogyny common to much art of the period, an attitude which condemned women for being so tempting whilst also secretly lusting after their bodies. Sensuality is remarkable for the way its oiled snake is so firmly lodged between the woman’s thighs. Stuck was never very interested in Christian themes—many of his other works are a Teutonic take on Classical subjects—so I wonder whether his use of the word “sin” was merely a fig leaf for delivering imagery he wouldn’t have otherwise been able to exhibit.

The Sin (1893).

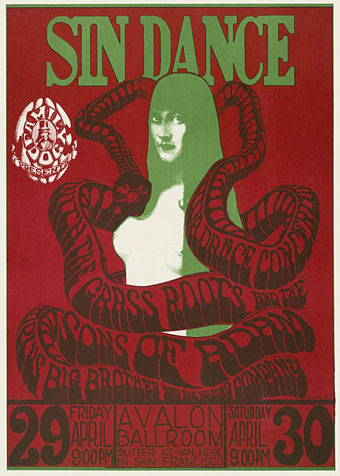

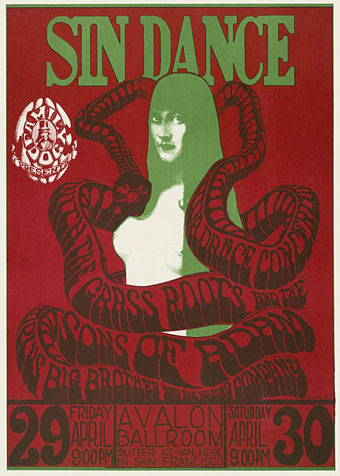

Sin Dance (1966) by Wes Wilson.

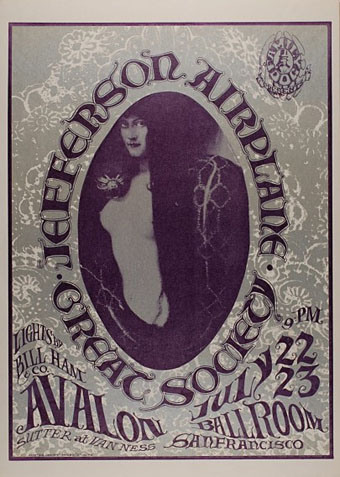

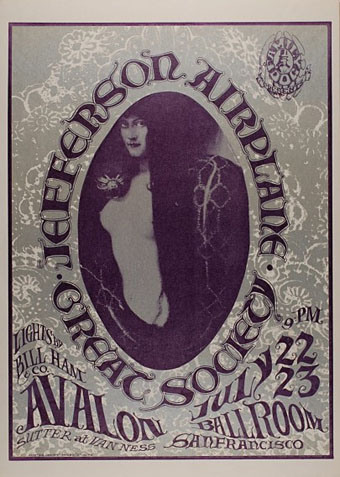

Symbolist art was rediscovered in the 1960s after decades of neglect, and the psychedelic poster artists happily plundered the art books for suitable imagery. Stuck’s Sin returned to the world in these two Avalon Ballroom posters. Wes Wilson’s Sin Dance was a design for an event which was cancelled so this might explain why the same painting appeared a few months later on a Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley poster. The Mouse & Kelley version was printed with metallic inks.

For more of Franz Stuck’s work see WikiPaintings.

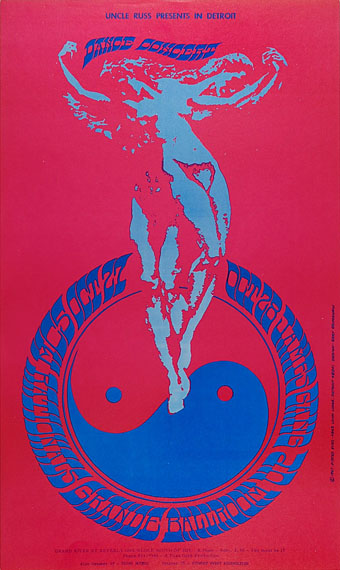

Jefferson Airplane at the Avalon Ballroom (1966) by Mouse & Kelley.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Serpentine pulchritude

• Salammbô illustrated

• The Feminine Sphinx

• Men with snakes