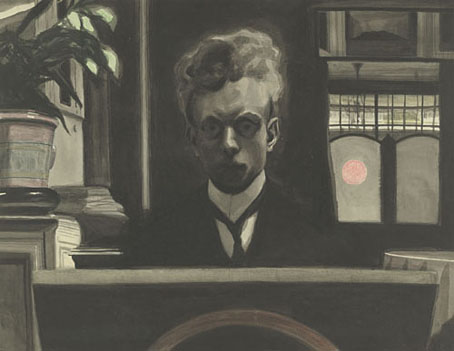

Self-portrait (1907).

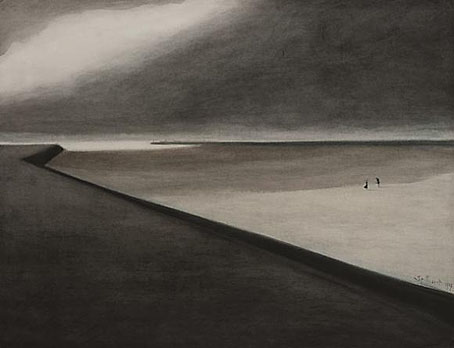

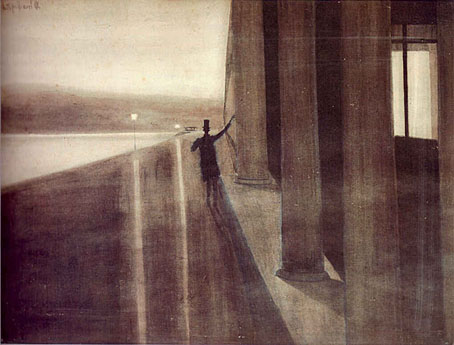

Yesterday’s post gives me an excuse to draw further attention to Belgian Symbolist Léon Spilliaert, an artist whose gloomy and mysterious early style is easy to recognise once you’ve seen a couple of his pictures. Spilliaert grew up in Ostend so the Belgian coast dominates his pastels which renounce sunlit beach scenes in favour of windswept vistas. The Impressionists flocked to the coast to paint fluffy clouds and waves and parasols; Spilliaert gives us monochrome shades and oppressively empty views.

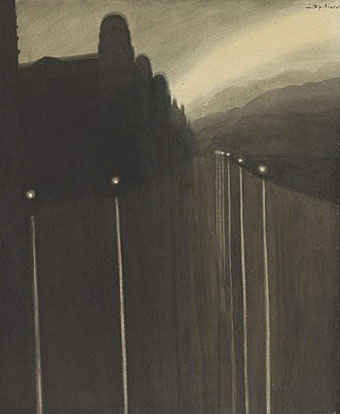

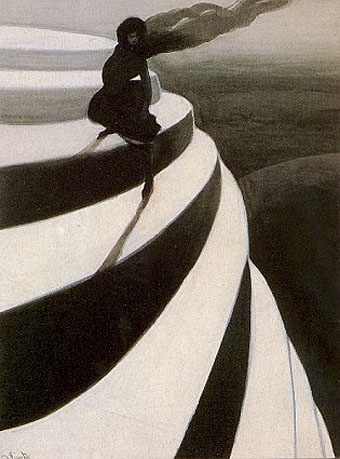

One of my books says Spilliaert suffered from insomnia which may explain his fondness for nocturnal scenes. But when you see the self-portraits where he looks less like a human being and more like a refugee from a film by the Brothers Quay you can assume a predilection for the dark. Later Spilliaert pictures are brighter and more representative of the seaside actuality but it’s the gloomy and mysterious fare for which he’s remembered today.

Dyke and Beach (1907).

Dyke at Night (1908).

Vertigo (1908).

The Night (1908).