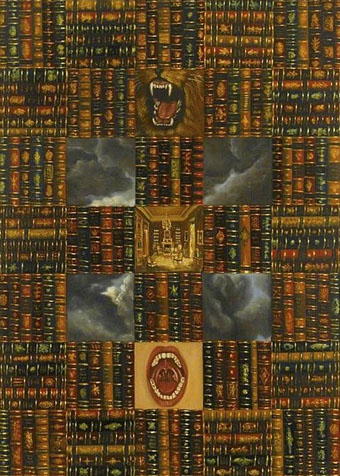

Black Hole (1987) by Suzanne Treister.

• “Most people who are considered heroes are always to be found messing about in someone else’s affairs, and I don’t think that’s very heroic.” Robert Altman talking in 1974 to Jan Dawson about The Long Goodbye.

• “Tea is calming, but alerting at the same time.” Natasha Gilbert on the science of tea’s mood-altering magic.

• Alien spaceship, Hammer horror? Philip Hoare on the pulsating visions of Harry Clarke.

“…world cinema, particularly European cinema…hasn’t shied away from sex and, in fact, has often found ways of using sex to tell a story. Movies like The Duke of Burgundy or Sauvage or BPM gracefully integrate eroticism into the narrative—even when the sex itself is far from graceful. Even the American films that have focused on sex tend to do it with a leer and luridness, regarding sex with a certain narrative fetishism, as opposed to matter-of-factly.”

Rich Juzwiak talking to Catherine Shoard about the current state of sex in the cinema

• Chernobyl again: photographs by David McMillan from inside the exclusion zone.

• Lasting Marks: the 16 men put on trial for sadomasochism in Thatcher’s Britain.

• Before Tarkovsky: Michael Brooke on the Russian TV adaptation of Solaris.

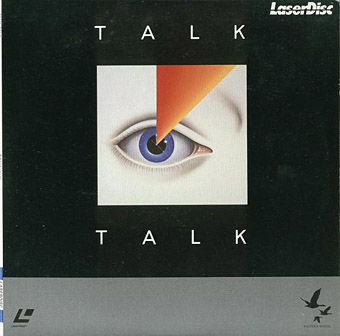

• Mix of the week: XLR8R Podcast 588 by Rouge Mécanique.

• Dustin Krcatovich on The Strange World of Mark Stewart.

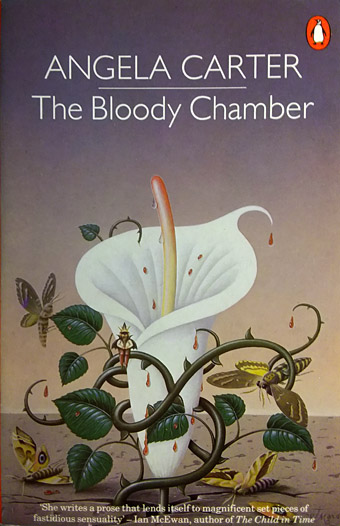

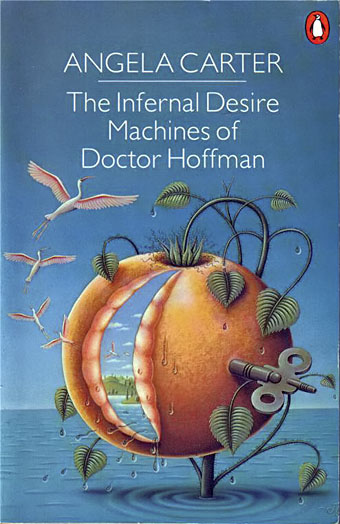

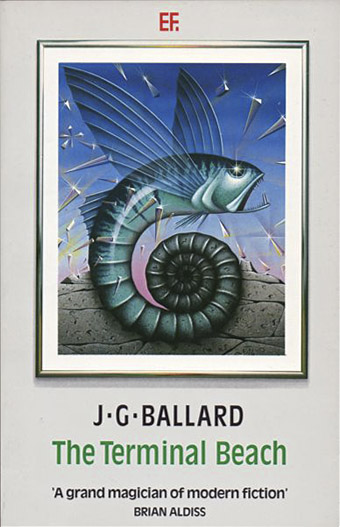

• Your Surrealist literature starter kit by Emily Temple.

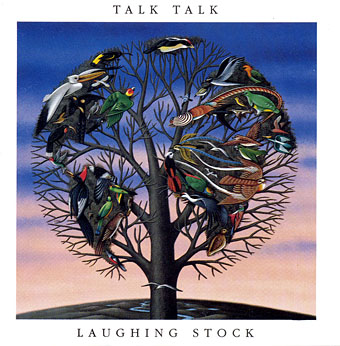

• John Peel’s Archive Things (1970)

• 5fathom: Things rich and strange

• Hole In The Sky (1975) by Black Sabbath | Thru The Black Hole (1979) by Metabolist | Black Hole (1993) by Total Eclipse