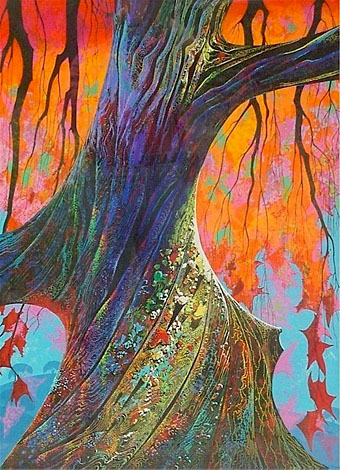

Fire, Red and Gold (1990) by Eyvind Earle.

• Roger Penrose won a Nobel Prize recently for his work in physics. I read one of his books a few years ago, and was intimidated by the “simple” equations, but I always like to hear his ideas. This 2017 article by Philip Ball is an illuminating overview of Penrose’s life and work.

• At Dangerous Minds: Joe Banks on the incidents that led to Lemmy’s dismissal from Hawkwind in 1975, an extract from Hawkwind: Days of the Underground. The book is available from Strange Attractor in Europe and via MIT Press in the USA.

• “Not married but willing to be!”: men in love (with each other) from the 1850s on. It’s always advisable to take photos like these with a pinch of salt but several of the examples are unavoidably what they appear to be.

Most of all, this resolutely collaborative production stood against the vanity and careerism of individual authorship; Breton called it the first attempt to “adapt a moral attitude, and the only one possible, to a writing process.” The text itself is peppered with readymade phrases, advertising slogans, twisted proverbs, and pastiches of such admired predecessors as Rimbaud, Apollinaire, and Lautréamont, whose pluralistic credo, “Poetry must be made by all. Not by one,” anticipates the sampling aesthetic by a century. But the intensity was draining, and as the book moves toward its final pages and the writing becomes increasingly frenetic, you can almost feel the burnout taking hold. After eight days, fearing for his and Soupault’s sanity, Breton terminated the experiment.

Mark Polizzotti reviews a new translation by Charlotte Mandell of The Magnetic Fields by André Breton and Philippe Soupault

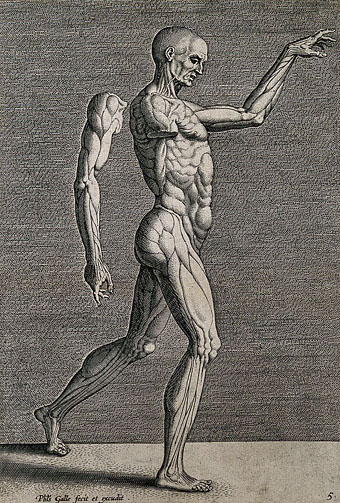

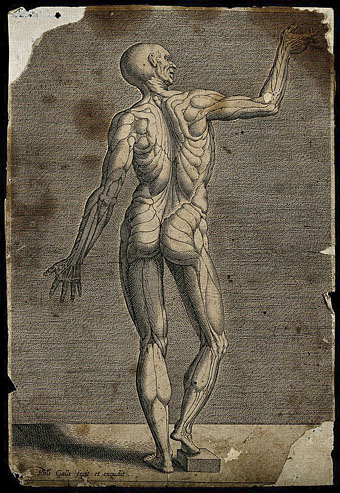

• The hide that binds: Mike Jay reviews Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin by Megan Rosenbloom.

• “A photographer ventures deeper into Chernobyl than any before him.” Pictures from Chernobyl: A Stalker’s Guide by Darmon Richter.

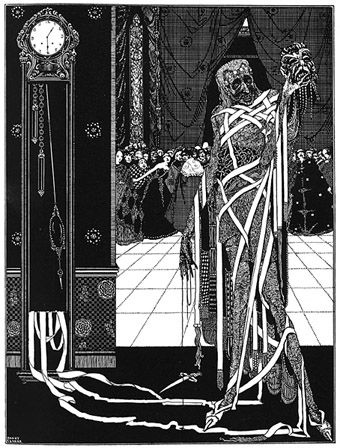

• John Van Stan’s reading of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley uses my illustrations (with my permission) for each of its chapters.

• Susan Jamison, one of the artists in The Art of the Occult by S. Elizabeth, talks to the latter about her work.

• William Hope Hodgson: The Secret Index. A collection of Hodgson-related posts at Greydogtales.

• Gee Vaucher talks to Savage Pencil about her cover art for anarchist punk band, Crass.

• Weird, wacky and utterly wonderful: the world’s greatest unsung museums.

• Tom Cardamone chooses the best books about Oscar Wilde.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Jean-Pierre Melville Day.

• You by The Bug ft. Dis Fig.

• Magnetic Dwarf Reptile (1978) by Chrome | Magnetic Fields, Part 1 (1981) by Jean-Michel Jarre | Magnetic North (1998) by Skyray