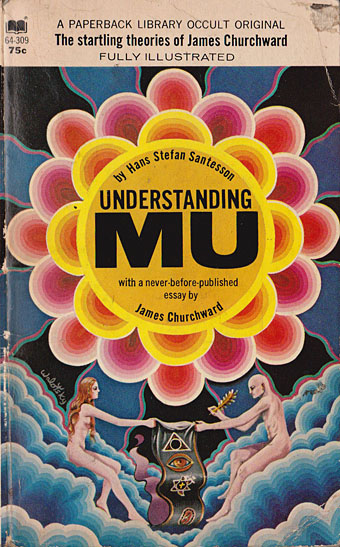

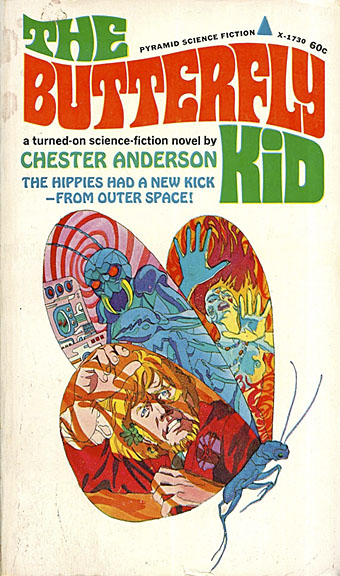

Cover art by Gray Morrow; design by Henry Berkowitz, 1967.

• “Dial-a-Poem received more than a million calls before it lost funding and ended in 1971. There were complaints of indecency, claims that the poems incited violence. The FBI investigated…” Ralf Webb on John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem project which is still active at the US and UK numbers on this page.

• Mixes of the week: Halloween approaches so for those who require themed mixes you can take your pick from these selections by Kaptain Carbon; at The Wire there’s a Halloween-free mix by Kuunatic.

• New music: New Moon by Laetitia Sadier, and The Reinterpretation Of Dreams (Remixed) by Tomoroh Hidari; not-so-new music: Velocity Of Sleep by Kali Malone.

The activist’s whole identity is tied up in him being denied, as opposed to him manifesting. Nobody can give you your freedom. You ARE free. It is your natural state, okay? You can give it all away if you want, but: no. I can’t GIVE you your rights. I can’t give you your freedom. And to go and beg the Man for your rights and BEG the Man for your freedom? LIVE your freedom.

One of Berg’s phrases was “life actor.” “Theatre of the streets.” All of this as theatre. As opposed to in a different arena you would call politics or activism or so on. But using theatre as a way to open doors that might not be opened if someone was approaching it in other ways. Out of that comes this whole sense of “create the reality you want to live in.” Which is a powerful, profound concept. People are trapped in the paradigm: you can’t even think there is an outside of the box. Just that notion of thinking, and living outside that paradigm, was real powerful stuff.

Claude Hayward of the San Francisco Diggers talking to Jay Babcock for the eighth installment of Jay’s verbal history of the hippie anarchists

• Joanna Moorhead on the creation of the Mae West lips sofa, a collaboration between Salvador Dalí and Edward James.

• The latest book from Rixdorf Editions is Papa Hamlet by Arno Holz and Johannes Schlaf.

• At Sweet Jane’s Pop Boutique: Op and Pop | Art Forms in Furnishing (1966).

• Denis Bovell’s favourite music.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Coffins.

• Love At Psychedelic Velocity (1966) by The Human Expression | Hamlet (Pow, Pow, Pow) (1982) by The Birthday Party | The Art Of Coffins (2002) by Bohren & Der Club Of Gore