1: The album

Back in the 1990s, when it became apparent that record companies were committed to never-ending CD reissues of their most popular albums, I suggested to a friend that this development would eventually give us releases of the unmixed recordings which the listener would then have to mix themselves: “Now you can be George Martin!” My suggestion wasn’t entirely serious, and there are many reasons why this will never happen, but the wholesale remixing of “classic” albums has been a trend now for ten years or more, and will no doubt continue. It’s easy to see endless reissues as a pernicious development—how many more copies of The Dark Side Of The Moon does the world need?—but I can think of one or two albums which would benefit from a reappraisal of their original mixes. The first two sides of Amon Düül II’s Dance Of The Lemmings, for example, have always sounded sonically inferior to the group’s other albums. The first side in particular is swamped by bass, and the drums, which are so prominent on the previous album, Yeti, are buried in the mix. Given the overtly psychedelic nature of the cover art I sometimes wonder whether anyone in the studio was drug-free during the recording.

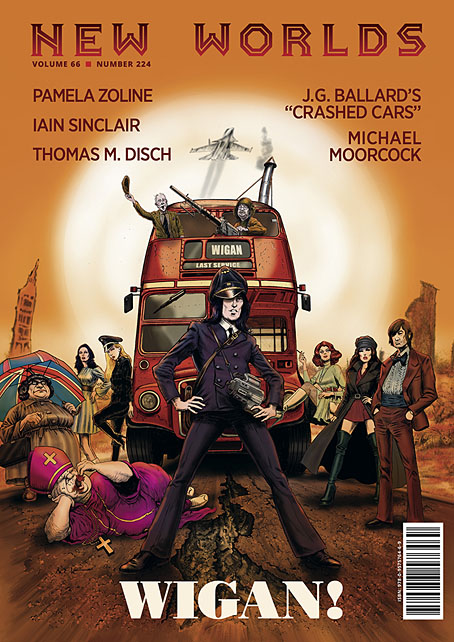

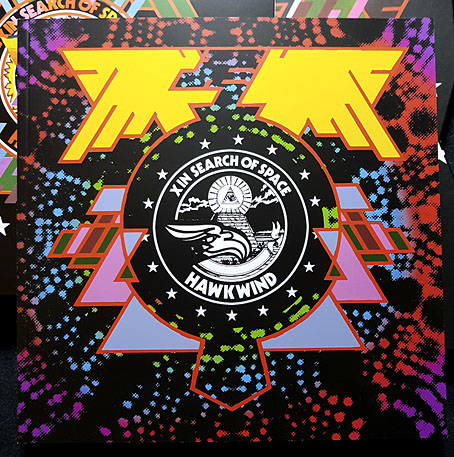

Hawkwind shared a record label with Amon Düül II for their first six albums, and the groups are further connected by bass player Dave Anderson who played on Düül’s Yeti in 1970 and Hawkwind’s In Search Of Space in 1971. The latter has just been reissued by Cherry Red in a variety of formats which include the three-disc package (2 x CD and a blu-ray disc) that arrived here at the weekend. The set features two new mixes of the entire album (one of them being the de rigueur 5-channel surround mix), a couple of outtakes, both sides of the Silver Machine single, plus the promo film for the single. The set also contains a substantial booklet which incorporates a reprint of the 24-page logbook that came with early pressings of the album. More about that below.

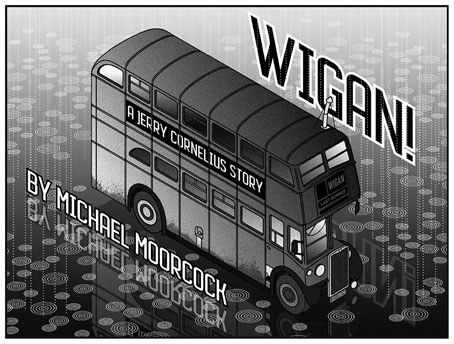

Hawkwind didn’t arrive as fully-fledged cosmic voyagers on their self-titled debut in 1970, it’s here on their second album that the group myth takes flight, presenting the band as travellers through time and space, or “Sonic Assassins” as they were depicted shortly before the album’s release in Codename: “Hawkwind”, a two-page promotional comic strip created by Michael Moorcock and Jim Cawthorn. Many British bands were playing with space themes in 1971 but Hawkwind were the only group to adopt the trappings of science fiction as essential elements of their persona, elements that persisted from one album to the next. In Search Of Space is loosely spacey on the musical side—You Shouldn’t Do That is the earliest example of a future Hawkwind staple, the extended mantra-like groove over which synthesizers swoop and burble—but it’s the album package created by Barney Bubbles and (in the logbook) Robert Calvert that dispels the ambiguity of songs like Master Of The Universe and Adjust Me in a science-fiction scenario where the “space” referred to by the title is dimensional as well as cosmological, with the group’s flattened spacecraft embodied by the physical album. None of this is suggested by the music, you need to read the logbook as well, but the book and the die-cut record sleeve help to frame what would otherwise be a collection of disparate rock songs into a complex artistic statement.

When it comes to the remixing of albums I’ve been sceptical of the benefits of the trend. For the past few years Steven Wilson has been the prime remixer of music from the 1970s and 80s; among other things he remixed Hawkwind’s Warrior On The Edge Of Time and the albums on last year’s Days Of The Underground set, all of which are worth hearing. Less essential have been his new mixes for King Crimson and Tangerine Dream, the latter especially where there’s little discernible difference between the old and new versions. I think the main attraction for many listeners will be the 5-channel surround mixes, especially in the case of Tangerine Dream, but I don’t have a 5-channel sound system so can’t say how effective they are. The new In Search Of Space mixes are the work of another Steve, Stephen W. Tayler, whose reworking of the album has taken me by surprise, giving it a radically different sound rather than the discreet adjusting of levels and instrumentation that I was expecting. Dave Brock has said in interviews that he always dropped acid before making the final mix of the Hawkwind albums up to Warrior On The Edge Of Time, which may explain why In Search Of Space has always sounded rather thin and dry, while the album that followed it, Doremi Fasol Latido, is a bludgeon by comparison, with everything compressed into the wall of sound which Hawkwind had developed in their live performances. Tayler’s new mix of Master Of The Universe is revelatory, bolstering the bottom end and emphasising the inverted echoes on Nik Turner’s voice, while You Shouldn’t Do That explodes into jet-propelled life. Everything sounds more substantial, and possibly more cosmic; I’ve not done a side-by-side comparison yet but I think Tayler has given greater emphasis to the effects throughout the album, especially all the swooshing and burbling electronic instruments. If you’ve ever shared my scepticism about the remixing trend then Tayler’s work here should be considered an argument in its favour.

Continue reading “Space is one trip: the Hawkwind takes off”