Seven pages more at the Opera Gallery and another page here.

Via Boing Boing.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Science fiction

Seven pages more at the Opera Gallery and another page here.

Via Boing Boing.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

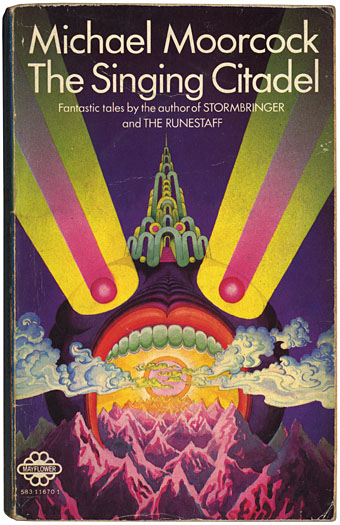

The Singing Citadel (1970).

Michael Moorcock’s Elric books are being prepared for republication by Del Rey in the US next year. I’ve assisted with some minor parts of this preparation, including sourcing pictures from Savoy’s edition of Monsieur Zenith the Albino. (Anthony Skene’s albino anti-hero is a precursor of Moorcock’s albino anti-hero.)

Discussion of the Elric books with Dave at Savoy prompted my excavation of this battered Mayflower paperback from the retired book boxes. This slim volume collected four fantasy stories: the title piece (possibly the first Elric story I read), Master of Chaos, The Greater Conqueror and To Rescue Tanelorn…. I’d forgotten about the garishly strange cover, one of many that Bob Haberfield produced for Moorcock’s books during the 1970s. Haberfield is one of a number of cover artists from that period who worked in the field for a few years before moving on or vanishing entirely. The swirling clouds derived from Tibetan Buddhist art identify this as one of his even without the credit on the back; later pictures were heavily indebted to Eastern religious art and while technically more controlled they lack this cover’s berserk intensity. Haberfield’s site has a small gallery of his splendid paintings, including a rare horror work, his wonderfully eerie cover for Dagon by HP Lovecraft.

Searching for more Haberfield covers turned up these two examples, both part of the SciFi Books Flickr pool, a cornucopia of pictures by vanished illustrators. Browsing that lot is like being back inside the In Book Exchange, Blackpool, circa 1977. The digitisation of the past continues apace at the Old-Timey Paperback Book Covers pool and the Pulp Fiction pool. Don’t go to these pages if you’re supposed to be doing something else, it’s easy to find yourself saying “just one more” an hour later.

And in other Moorcock-related news, Jay alerts me today to the existence of an archive of New Worlds covers, something I’d been hoping to see for a long time. New Worlds was one of the most important magazines of the 1960s, mutating under Moorcock’s editorship from a regular science fiction title to a hothouse of literary daring and experiment. As with so many things in that decade, the peak period was from about 1966–1970 when the magazine showcased outstanding work from Moorcock himself, JG Ballard, Brian Aldiss, Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delany, M John Harrison, Norman Spinrad and a host of others. For a time it seemed that a despised genre might be turning away from rockets and robots to follow paths laid down by William Burroughs, Salvador Dalí, Jorge Luis Borges and other visionaries. We know now that Star Wars, Larry Niven and the rest swept away those hopes but you can at least go and see covers that pointed to a future (and futures) the world rejected.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer

• 100 Years of Magazine Covers

• It’s a pulp, pulp, pulp world

The incomparable Culture Archive presents an embarrassment of riches in scanned form; if only there were more sites as good as this. Easier for you to go and look for yourself than waste time reading a poor description of the place.

Random browsing turned up pages from the Earl of Birkenhead’s study of the state of the world a century from 1930. But it’s not the Earl’s prognostications that concern us here, rather the book’s airbrush illustrations by E McKnight Kauffer, an artist and designer better known for his Art Deco poster designs like Metropolis (1926) below.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Metropolis posters

• Frank Lloyd Wright’s future city

Image-heavy post! Please be patient.

Four designs for three bands, all by the same designer, the versatile and brilliant Barney Bubbles. A recent reference over at Ace Jet 170 to the sleeve for In Search of Space by Hawkwind made me realise that Barney Bubbles receives little posthumous attention outside the histories of his former employers. Since he was a major influence on my career I thought it time to give him at least part of the appraisal he deserves. His work has grown in relevance to my own even though I stopped working for Hawkwind myself in 1985, not least because I’ve made a similar transition away from derivative space art towards pure design. Barney Bubbles was equally adept at design as he was at illustration, unlike contemporaries in the album cover field such as Roger Dean (mainly an illustrator although he did create lettering designs) and Hipgnosis (who were more designers and photographers who drafted in illustrators when required).

Colin Fulcher became Barney Bubbles sometime in the late sixties, probably when he was working either part-time or full-time with the underground magazines such as Oz and later Friends/Frendz. He enjoyed pseudonyms and was still using them in the 1980s; Barney Bubbles must have been one that stuck. The Friends documentary website mentions that he may have worked in San Francisco for a while with Stanley Mouse, something I can easily believe since his early artwork has the same direct, high-impact quality as the best of the American psychedelic posters. Barney brought that sensibility to album cover design. His first work for Hawkwind, In Search of Space, is a classic of inventive packaging.

Update: BB didn’t work with Mouse in SF, I’ve now been told.

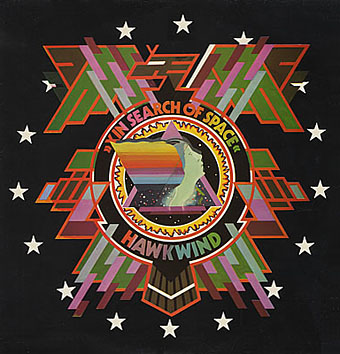

Hawkwind: In Search of Space (1971).

It’s fair to say that Hawkwind were very lucky to find Barney Bubbles, he immediately gave their music—which was often rambling and semi-improvised at the time—a compelling visual dimension that exaggerated their science fiction image while still presenting different aspects of the band’s persona. In Search of Space is an emblematic design that opens out to reveal a poster layout inside. One of the things that distinguishes Barney Bubbles’ designs from other illustrators of this period is a frequent use of hard graphical elements, something that’s here right at the outset of his work for Hawkwind.

This album also included a Bubbles-designed “Hawklog”, a booklet purporting to be the logbook of the crew of the Hawkwind spacecraft. I scanned my copy some time ago and converted it to a PDF; you can download it here.

There are few people who really change your life but Robert Anton Wilson—who died earlier today—certainly changed mine. Wilson’s Illuminatus! trilogy (written with Robert Shea) was my cult book when I was at school in the 1970s, a rambling, science fiction-inflected conspiracy thriller that opened the doors in my teenaged brain to (among other things) psychedelic drugs, HP Lovecraft, James Joyce, William Burroughs and Aleister Crowley as well as being a crash-course in enlightened anarchism. I’ve had people criticise the books to me since for their ransacking of popular culture but this was partly the point, they were collage works, and they worked as a perfect introduction for a young audience to worlds outside the usual circumscribed genres.

The philosophical side of Wilson’s work was probably the most important at the time (and remains so now), his “transcendental agnosticism” made me start to question the adults around me who were trying to force my life to go in a direction I wasn’t interested in at all. I’m sure I would have resisted that kind of pressure anyway but the value of RAW’s writings in Illuminatus! and the later Cosmic Trigger came with being given an intelligent rationale for those decisions; I couldn’t necessarily articulate why I was “throwing my life away” by wanting to drop out of the whole education system but Wilson’s work had convinced me it was the right thing to do. I still mark the true beginning of my life as May 1979, the month I left school for good.

He wouldn’t want us to be maudlin, I’m sure. It’s typical for a writer who spent so much of his life writing about drugs and coincidences that he managed to die on Albert Hofmann’s birthday. So I’ll just say thank you Robert, for changing my life. And Hail Eris!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Absolute Elsewhere