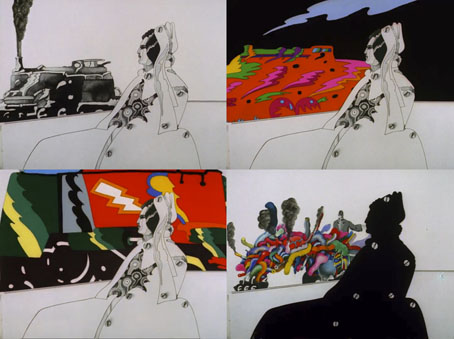

There’s more to Heinz Edelmann than the designs he created for Yellow Submarine, as Edelmann himself often used to remind people. And there’s more to his work for animated film than the Beatles’ exploits. Der Phantastische Film is a short introductory sequence for a long-running German TV series which has been doing the rounds for a number of years. Brief it may be but a couple of the monstrous details resemble those that Edelmann put into his covers for Tolkien’s books.

Edelmann had plans to capitalise on the success of Yellow Submarine with more films like this when he set up his own animation company, Trickfilm, but the only other example is The Transformer, a short about steam trains which he designed. (The direction was by Charlie Jenkins, with animation by Alison De Vere and Denis Rich.) Given the persistent popularity of Yellow Submarine I keep hoping someone might revive its style for something new. The first animated feature directed by Marcell Jankovics, Johnny Corncob, comes close but lacks the trippy Surrealism of the Beatles film. The Japanese can certainly do trippy Surrealism (see Mind Game or Paprika) but I’ve yet to see anything that approaches the Edelmann style. Johnny Corncob, incidentally, is now available on Region B blu-ray from Eureka. It’s worth seeing but the main film in the set, Son of the White Mare, is Jankovics’s masterpiece.

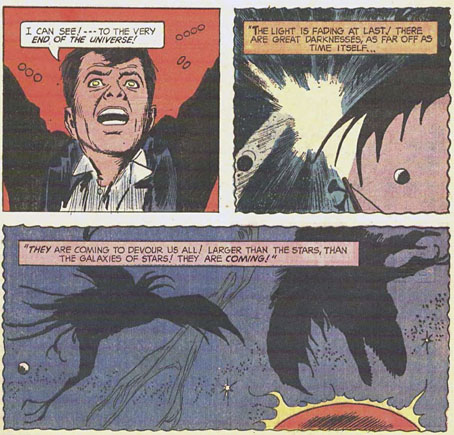

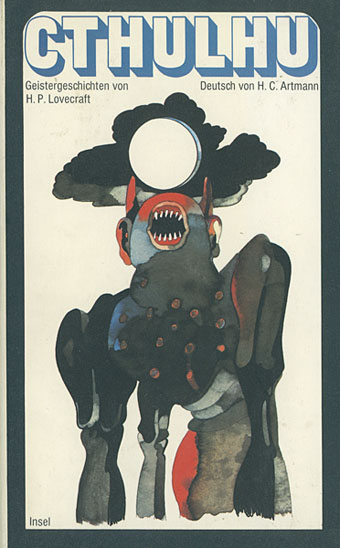

On a slightly related note, until today I hadn’t looked at ISFDB.org for Heinz Edelmann’s genre credits so I hadn’t seen this Lovecraft cover before. Hard to tell if this creature is supposed to be Cthulhu or Wilbur Whateley’s brother when The Dunwich Horror is one of the stories in the collection. Either way, it belongs in the Sea of Monsters. Insel Verlag published this one in 1968, a year before launching their special imprint devoted to fantastic literature, Bibliothek des Hauses Usher.

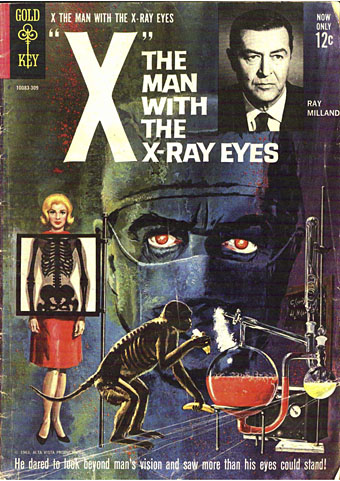

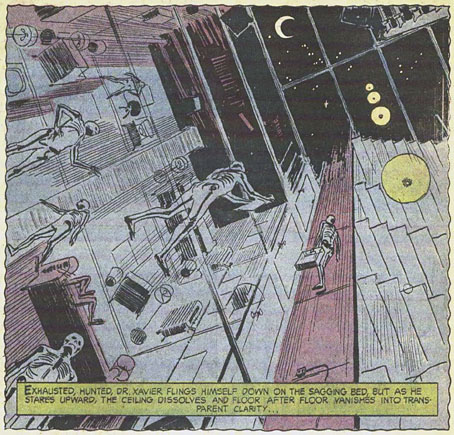

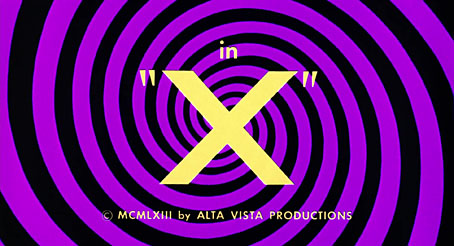

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Return to Pepperland

• The groovy look

• The Sea of Monsters

• Yellow Submarine comic books

• Heinz Edelmann