The Natural History Museum of Oslo University has opened an exhibition dedicated to homosexuality in the animal kingdom.

Today we know that homosexuality is a common and widespread phenomenon in the animal world. Not only short-lived sexual relationships, but even long-lasting partnerships; partnerships that may last a lifetime.

The exhibit puts on display a small selection among the more than 1500 species where homosexuality have been observed. This fascinating story of the animals’ secret life is told by means of models, photos, texts and specimens. The visitor will be confronted with all sorts of creatures from tiny insects to enormous spermwhales.

How can we know that an animal is homosexual? How can homosexual behaviour be consistent with what we have learned about evolution and Darwinism?

Sadly, most museums have no traditions for airing difficult, concealed, and possibly controversial questions. Homosexuality is certainly such a question. We feel confident that a greater understanding of how extensive and common this behaviour is among animals, will help to de-mystify homosexuality among people. At least, we hope to reject the all too well known argument that homosexual behaviour is a crime against nature.

Naturally (ahem), this has attracted the ire of the usual god-botherers who are happy to ignore inconvenient Scriptural declarations about loving your neighbour when sending the museum directors hate mail. Unfortunately for the bigots, evidence about homosexuality being very much a part of the natural world continues to mount (pardon the pun again…), as shown in an article in US science magazine, Seed, earlier this year. That won’t convince the American (and other) Talibans, of course, but then if it was up to them we’d still be burning witches and thinking that the sun orbited the earth.

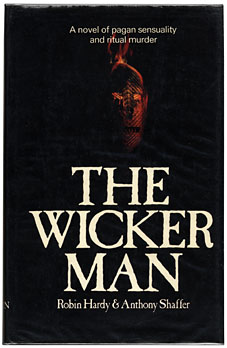

Left: The scarce first edition of the Hamlyn novelisation. From the Coulthart library.

Left: The scarce first edition of the Hamlyn novelisation. From the Coulthart library.