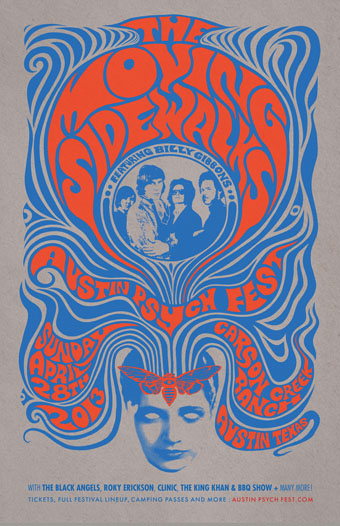

Poster design by Mishka Westell for this month’s Austin Psych Fest. Billy Gibbons’ pre-ZZ Top psychedelic outfit, The Moving Sidewalks, surprised everyone by reforming for a New York gig last month, their first performance together in 44 years.

• Pye Corner Audio played the Boiler Room, London, last week, and remixed a track from FC Judd’s Electronics Without Tears. Also on the latter is Chris Carter who talks about his own remix (and the “Radiophonic” Mr Judd) here.

• Tom Bianchi’s Fire Island Pines, Polaroids of New York’s gay enclave from 1975–1983. Related: In Conversation with the Violet Quill: Andrew Holleran, Felice Picano, and Edmund White.

• From 2011: Sex, prison and lost ligatures: The story of Herb Lubalin’s Avant Garde typeface. Related: The ITC Avant Garde Gothic group at Flickr.

• Music reissues: Tape Works 1981–1982 by Laughing Hands is out now, and Scott Walker’s early solo albums will be reissued in the summer.

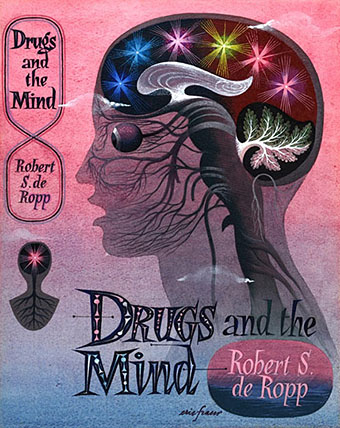

Drugs and the Mind (ii), a cover design from 1957 by Eric Fraser (1902–1983) whose illustrations and designs are in exhibition at the Chris Beetles gallery, London.

• At Ubuweb: William S. Burroughs + Brion Gysin + Genesis P-Orridge – Cold Spring Tape (1989).

• The World According to John Coltrane, an hour-long documentary.

• Neko Font: for when you need a word made of cats.

• 99th Floor (1967) by The Moving Sidewalks | Over Fire Island (1975) by Brian Eno | Ledge (1980) by Laughing Hands