Photography by Christopher Makos.

Category: {photography}

Photography

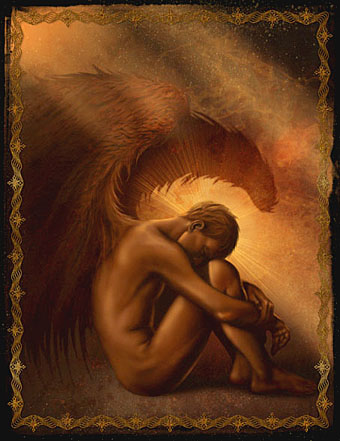

Angels 6: Paradise stands in the shadow of swords

The Guardian of Paradise by Franz Stuck (1889).

We’ll let Coil have the final word on the angel theme, the post title being taken from their Cathedral In Flames. Those words recognise—as does the painting above—that the Christian concept of Heaven is of a gated community guarded by warriors to keep the undesirable at bay.

Symbolist painter Franz Stuck was (as far as we know) robustly heterosexual but his angel isn’t far removed from the work of contemporary photographers like Anthony Gayton who specialise in teasing out the erotic undercurrents in this kind of imagery. Which brings us full circle, seeing as we started with Caravaggio and his distinct brand of religious subversion. The irony is that some of the more vocal elements of Christianity can’t help subverting themselves or their own messages, as John Patterson notes in his Guardian piece today, alluding not only to the Ted Haggard debacle but also to Haggard’s favourite artist, Thomas Blackshear, both of whom were discussed here in November. Patterson writes that the recent brand of bigoted fervour that’s swept America seems to have abated, or at least retreated, after threatening to become a mainstream force. Europe often seems a haven of healthy heathen sanity by comparison, a part of the undesirable world being kept outside the American Paradise. St. Peter now demands retinal scans, fingerprints and a biometric passport. Continual rumbles from Pope Maledict and his closeted cardinals are an increasing irrelevance, the background static of a dying regime. Paradise may be guarded by attractive angels but we can only look and never touch. As Patterson says, the devil has all the best tunes. And the best books and movies and games. And sex and fun. I know which side of the fence I’d rather be on.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The men with swords archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Gay for God

Angels 3: A diversion

On Monday Eroom Nala mentioned my Fallen Angel picture in one of the comments for the first angel posting. Here’s the picture in question (from 2004).

As I mentioned earlier, this was based on Jeune homme assis au bord de la mer (Young Man Sitting by the Seashore, 1836), the most well-known painting by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1809–1864). In a posting back in February I wrote about how this painting has become something of a gay icon over 170 years, with increasing numbers of artists and photographers working their own variations on the pose. As far as I was aware, I was the only person to have tried adding wings to the figure.

Now today I run across a great gallery of photographs by Jose Manchado who has his rather gorgeous model, Reuben, adopt the same pose then gives him a set of abstract wings.

Manchado’s other photographs are well worth a look. He also adds more realistic wings to a female model but since we’re concerning ourselves with male angels this week I’ll leave you to look for her.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The recurrent pose archive

Angels 2: The angels of Paris

Los Angeles, despite being the City of Angels, has few angels on display outside its cemeteries, whereas European cities are full of them. These are some of the ones that caught my attention in Paris this year.

Saint Michael (1860) by Francisque-Joseph Duret in the Place Saint-Michel.

More statues of Saint Michael. The one on the left is by Emmanuel Frémiet (1897), in the Musée D’Orsay. On the right is a detail from the roof of the Sacre Coeur.

The Jantar Mantar

Fran Pritchett’s site has a wealth of photos of Indian architecture, including many old views of temples and a substantial section devoted to Jaipur’s fascinating Jantar Mantar.

The Jantar Mantar is a collection of architectural astronomical instruments, built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then new capital of Jaipur between 1727 and 1733. It is modelled after the one that he had built for him at the then Mughal capital of Delhi. He had constructed a total of five such observatories at different locations, including the ones at Delhi and Jaipur. The Jaipur observatory is the largest of these.

The name is derived from yantra, instrument, and mantra, for chanting; hence the ‘the chanting instrument’. It is sometimes said to have been originally yantra mantra, mantra being translated as formula, although there is limited justification for this since in traditional spoken Jaipur language, the locals obfuscate the written Y syllable as J.

The observatory consists of fourteen major geometric devices for measuring time, predicting eclipses, tracking stars in their orbits, ascertaining the declinations of planets, and determining the celestial altitudes and related ephemerides. Each is a fixed and ‘focused’ tool. The Samrat Jantar, the largest instrument, is 90 feet high, its shadow carefully plotted to tell the time of day. Its face is angled at 27 degrees, the latitude of Jaipur. The Hindu chhatri (small domed cupola) on top is used as a platform for announcing eclipses and the arrival of monsoons.

Built of local stone and marble, each instrument carries an astronomical scale, generally marked on the marble inner lining; bronze tablets, all extraordinarily accurate, were also employed. Thoroughly restored in 1901, the Jantar Mantar was declared a national monument in 1948.

An excursion through Jai Singh’s Jantar is the singular one of walking through solid geometry and encountering a collective weapons system designed to probe the heavens.

The instruments are in most cases huge structures. They are built on a large scale so that accuracy of readings can be obtained. The samrat yantra, for instance, which is a sundial, can be used to tell the time to an accuracy of about a minute. Today the main purpose of the observatory is to function as a tourist attraction.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Garden of Instruments