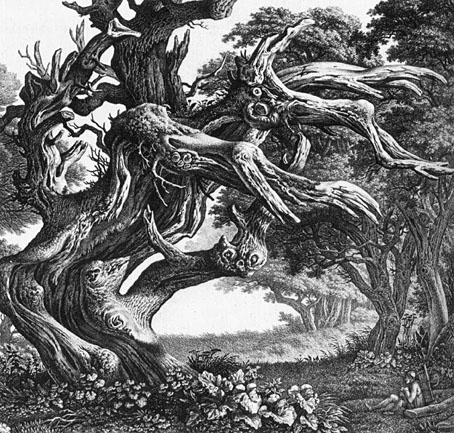

Fantastical Tree (c. 1830) by Carl Wilhelm Kolbe.

• “It’s just a square and a semi-circle at the end of the day.” Pete Adlington navigates the rapids of high-profile cover design for the UK edition of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and The Sun. I’m not always keen on the minimal approach but the Faber edition is a better design than the equally minimal US cover whose circle in a hand makes it look like a reprint of Logan’s Run. Faber also produced a limited edition with the sun circle wrapped onto sprayed page edges.

• “‘With a mysterious smile on her lips,’ writes the Chilean film director Alejandro Jodorowsky, ‘the painter whispered to me, “What you just dictated to me is the secret. As each Arcana is a mirror and not a truth in itself, become what you see in it. That tarot is a chameleon.”‘” The painter referred to is the now-ubiquitous Leonora Carrington whose own Tarot deck is investigated by Rhian Sasseen.

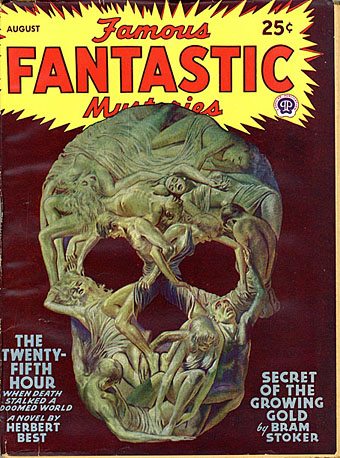

• “‘Horror is an emotion,’ Douglas E. Winter tells us. I would respectfully like to amend that assertion. Horror is a range of emotions. And each of these moods, if they are to be successful, must be cultivated differently.” Brian J. Showers offers his thoughts on horror fiction.

• “You move from awareness of—and preoccupation with—how sounds affect our bodies, into how that might create a web of connection with the external world—with the natural world.” Annea Lockwood talking to Jennifer Lucy Allan about her career as a composer and sound artist.

• Gay cruising and its geography in cinema and documentary, a list of films by Mike Kennedy. Related: Shiv Kotecha on O Fantasma (2000), a film by João Pedro Rodrigues.

• Coming from Strange Attractor in June: Coil: Camera Light Oblivion, a photographic record by Ruth Beyer of the first live performances by Coil from 2000–2002.

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine on The Star Called Wormwood (1941), a strange novel by Morchard Bishop.

• At Unquiet Things: Ephemeral and Irresistible: The Spectacular Still-life Botanical Drama of Gatya Kelly.

• “Fevers of Curiosity”: Charles Baudelaire and the convalescent flâneur by Matthew Beaumont.

• 1066 and all that: Explore the Bayeux Tapestry online.

• Mix of the week: Secret Thirteen Mix 311 by Arigto.

• New music: Terrain by Portico Quartet.

• Fever (1956) by Little Willie John | Fever (1972) by Junior Byles | Fever (1980) The Cramps