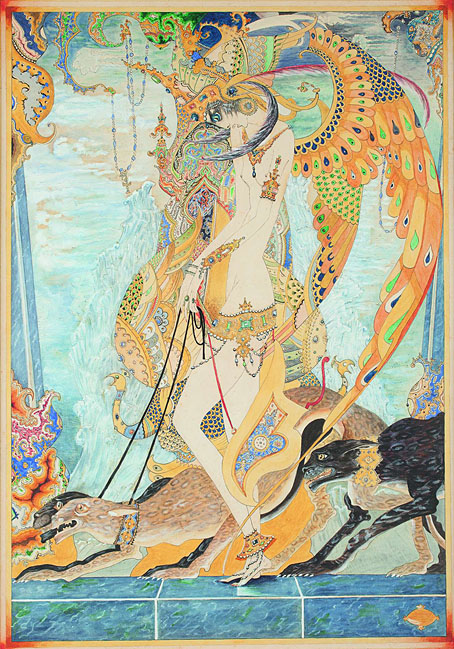

My music listening for the past week has comprised alternations between various Hawkwind albums and this, the latest release from Jon Hopkins. Ritual is so good I’ve been trying not to overplay it, a 40-minute composition divided into eight connected parts which is sufficiently beatless to be described as ambient, although the ambient tag usually refers to music that drifts quietly in the background. Ritual may work at low volumes but it generates an intensity that warrants immersion in its field of sound, especially on The Veil/Evocation where a slow and increasingly powerful detonation emerges from the boundless spaces. The album has been promoted with a pair of videos, a typical constituent of any high-profile release but one which in this case spoils the flow of the album where the music only fades to silence at the very end. The second video by UON Visuals does at least communicate something of Hopkins’ transcendent reach, an extension of the cover art into a glittering psychedelic vortex.

Ritual, Part II: Palace by UON Visuals.

It took me a while to get round to Hopkins’ brand of electronic music, mainly because his early releases don’t distinguish themselves very much from similar explorations of the post-techno landscape. Opalescent was his first album in 2001, a release that I now own but might not have bothered with if his work hadn’t improved a great deal over the past two decades. The discography gets really interesting with Singularity in 2018, an album whose thumping four-four rhythms continued the trend of previous releases but now with a distinct flavour of their own. The same goes for Hopkins’ use of the piano which, being classically trained, he plays with considerable skill. Music for Psychedelic Therapy followed Singularity, an unexpected swerve into ambient territory which abandoned any relation to the dancefloor for a kind of throwback to the better class of New Age albums being released in the 1980s, with natural sounds—wind, rain, bird and animal calls—mixed into the music. The New Age connection was reinforced by the final track which features a platitudinous monologue from the late Ram Dass, the American mystic formerly known as Richard Alpert who was one of the early promoters of psychedelic therapy in the 1960s along with his erstwhile colleague, Timothy Leary. I’d consider the album a perfect one if it wasn’t for this coda. With a few exceptions (William Burroughs, for one), I’ve never liked lengthy spoken-word pieces on otherwise instrumental albums, and Ram Dass seems especially out of place when he spent the latter part of his life proclaiming the virtues of meditation and Hindu-derived mysticism over psychedelic voyaging. The latest album applies the power of Singularity to the ambient spaces of Music for Psychedelic Therapy. It’s the best thing Hopkins has done to date. I can’t wait to hear what he does next.