A follow-up to last year’s list. Seeing as Joy Division are very much in the news at the moment with the release of Control and the re-issue of the albums, I thought a post-punk theme would be appropriate. The period which immediately followed punk in the late Seventies saw a lot of doom being imported into what was then still a proper alternative to the mainstream of popular music. This trend quickly ossified into the distinct and far less adventurous genres of goth and post Throbbing Gristle/Cabaret Voltaire industrial but between 1978 and 1982 everything was in a state of fascinating flux.

Hamburger Lady (1978) by Throbbing Gristle.

TG’s heart-warming ode to a burns victim.

6am (1979) by Thomas Leer & Robert Rental.

Leer and Rental’s The Bridge album was originally one of the few none-Throbbing Gristle releases on TG’s Industrial label, one half songs, the other moody electronic instrumentals. 6am perfectly conjures a picture of empty streets at dawn and sounds like a precursor of Ennio Morricone’s score for The Thing.

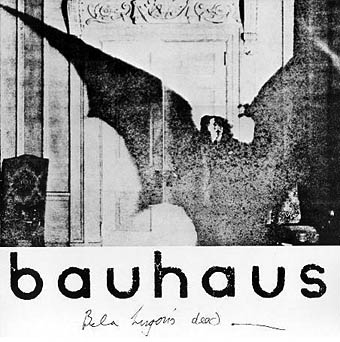

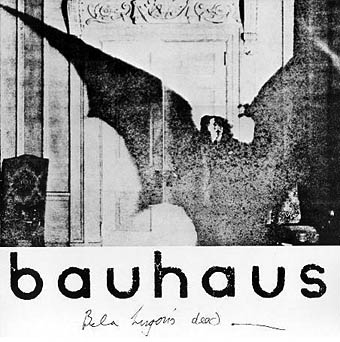

Bela Lugosi’s Dead (1979) by Bauhaus.

The first Bauhaus single and the only song of theirs I liked. Put to great use at the beginning of the otherwise pretty risible The Hunger.

Day Of The Lords (1979) by Joy Division.

If anything shows that Ian Curtis was a Romantic in the 19th century sense, it’s this grandiose wallow in the atrocities of history. “Where will it end?”

James Whale (1980) by Tuxedomoon.

Church bells toll and a lonely violin shrieks for the director of the Universal Frankenstein films.

Halloween (1981) by Siouxsie & the Banshees.

With a title like that, how could it not be included here?

Goo Goo Muck (1981) by The Cramps.

Always superior collagists of rockabilly weirdness and early garage riffs, The Cramps started out in the horror camp (“camp” being a big part of their act) with the Gravest Hits EP. Goo Goo Muck was a cover of a great single by (I kid not) Ronnie Cook & the Gaylads. “When the sun goes down and the moon comes up / I turn into a teenage goo goo muck.”

Raising The Count (1981) by Cabaret Voltaire.

An obscure moment of resurrection originally on the Rough Trade C81 cassette compilation from the NME.

Gregouka (1982) by 23 Skidoo.

Gregorian monks meet Moroccan pipes and drums with the result sounding like a voodoo ceremony taking place in cathedral catacombs.

The Litanies Of Satan (1982) by Diamanda Galás.

The formidable Ms Galás was part of last year’s list and her first album is just as hair-raising as her later works. The second part is the marvellously titled Wild Women With Steak-knives (The Homicidal Love Song For Solo Scream).

Happy Halloween!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• White Noise: Electric Storms, Radiophonics and the Delian Mode

• The Séance at Hobs Lane

• A playlist for Halloween

• Ghost Box