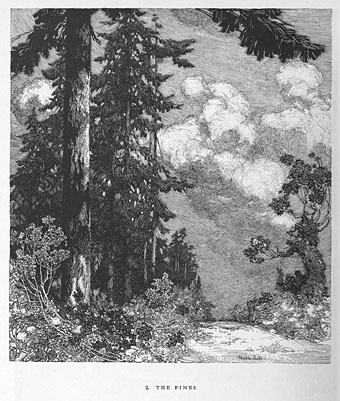

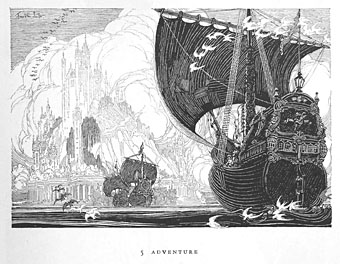

One of the hazards of working for ephemeral media such as magazines is that your work disappears from view once the magazine has left the news-stand, exiled to libraries and other archives. This is a particular problem for illustrators, as I’ve noted in the past with regard to artists such as Virgil Finlay; stories by popular writers will be reprinted but their illustrations tend to remain marooned in the pulp pages where they first appeared. Franklin Booth worked at the opposite end of the scale to Finlay, providing editorial and advertising illustrations for very unpulpy titles such as Harper’s and Scribner’s. He was, and still is, highly-regarded, but his illustrations aren’t as easy to find today as those of his contemporaries who spent more of their time working for book publishers.

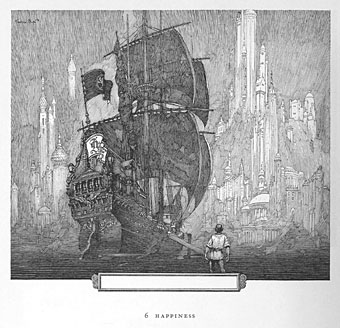

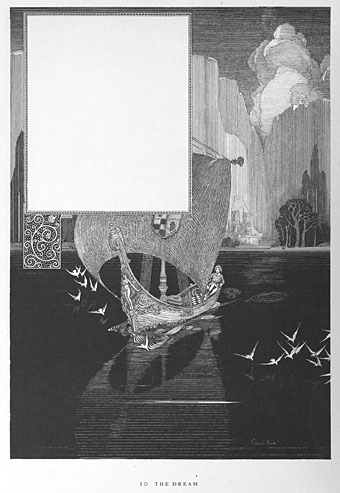

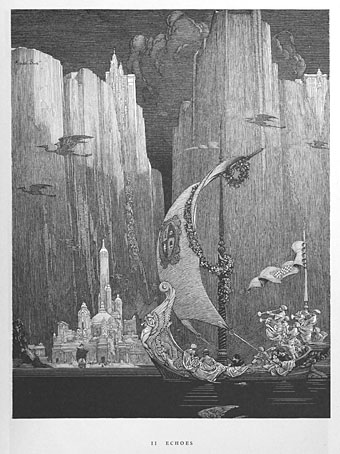

Franklin Booth: Sixty Reproductions from Original Drawings is a collection of the artist’s illustrations published in 1925, the most striking feature of which is the preponderance of fantastic scenes. Some of these are evidently story illustrations but the book lacks any notes about the origins of the drawings so we’re left to guess whether the same goes for the others, or whether these are examples of the artist indulging his imagination. Whatever the answer, Booth had a nice line in fantasy architecture, all soaring towers topped by cupolas and finials, which may explain the Booth influence in some of François Schuiten’s drawings. The building style is reminiscent of the Beaux-Arts confections that proliferated at international expositions in the years before the Deco idiom swept away superfluous decoration, something you also find in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland where the dream palaces could easily have been built to showcase the latest engineering marvels.

Note: All these images have been processed to remove the sepia tone of the paper.