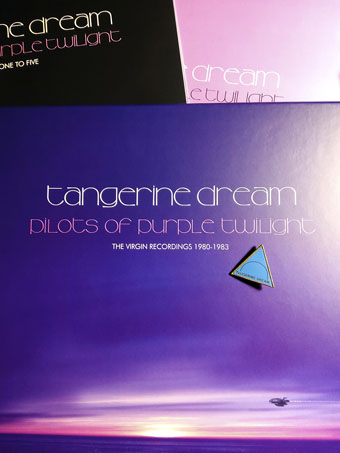

1982 tour badge not included.

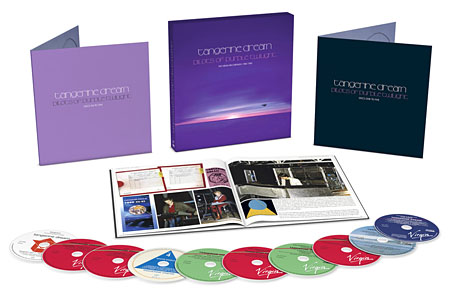

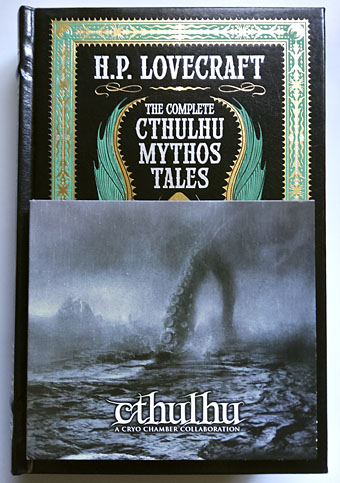

This arrived at last, after the usual shenanigans with Parcelforce and their blink-and-you-miss-em deliveries: 10 compact discs plus a large book that documents the final third of Tangerine Dream’s years on the Virgin label, when Johannes Schmoelling had joined to fill the gap left by Steve Jolliffe. These were all albums I bought as they were released, and I also saw the group for the first time on their 1982/83 tour, a performance from which is documented on the Logos live album. Consequently, I’ve always liked this period, and don’t regard it as lesser than the Peter Baumann years. The two phases of the group’s evolution are very different, in part because the technology they were using by 1980 was very different from the more cumbersome electronics of the 1970s: synthesizers were now polyphonic, sequencers were much more programmable, and digital synthesis had arrived. Tangerine Dream were early users of the PPG Wave, a digital synthesizer that allowed the recording and playback of sound samples. The Wave sound is prominent on all the albums from the Schmoelling period, giving the music a very different character to the earlier Moog-and-Mellotron recordings.

Pilots Of Purple Twilight doesn’t contain as many revelations as the previous In Search Of Hades box but there are some rarities here which are either making their first appearance on CD or their first official release in any form. The Logos album was 50 minutes of a much longer set from the Dominion Theatre, London, which is now available in full on two discs. (The original Logos album appeared in the shops only five or six weeks after it was recorded, something that amazed and delighted me at the time.) The full concert had been available in the past as part of the fan-produced Tangerine Leaves bootleg series but the recording was typical of the low quality that distinguishes the Leaves discs from the superior Tangerine Tree series. By 1982 the improvisation quotient in Tangerine Dream’s live performances had diminished, so the Dominion concert provides a representative snapshot of the tour as a whole. Some of the new music—the so-called Logos suite—appeared later in the soundtrack of Michael Mann’s cult horror film, The Keep (1983), and another of the rarities here is a variant of one of several discs that have been released as The Keep soundtrack. Unfortunately for Keep enthusiasts, the disc in the Pilots box is the least interesting of the two main Keep releases, comprising a small amount of music which did appear in the film together with a much larger percentage that didn’t. Voices In The Net refers to the 1997 limited-edition release of this music as having been “tangentized” which is their term for old recordings that Edgar Froese later reworked. This pushes the music even further away from the original soundtrack recordings of 1982/82; one of the tracks, Arx Allemand, is a terrible faux-Baroque confection that even Rick Wakeman would reject as sub-standard. The new disc also omits 3 tracks from the 1997 release: Sign In The Dark, Weird Village, and Love And Destiny. There is a Keep soundtrack that features more of the actual music from the film but for that you’ll have to search torrent or bootleg sites for Tangerine Tree Volume 54.

Edgar Froese, Chris Franke and Johannes Schmoelling performing in Perth, Australia, in February 1982. Edgar is playing a PPG Wave 2 while Johannes has a Roland keyboard, probably a Jupiter 8.