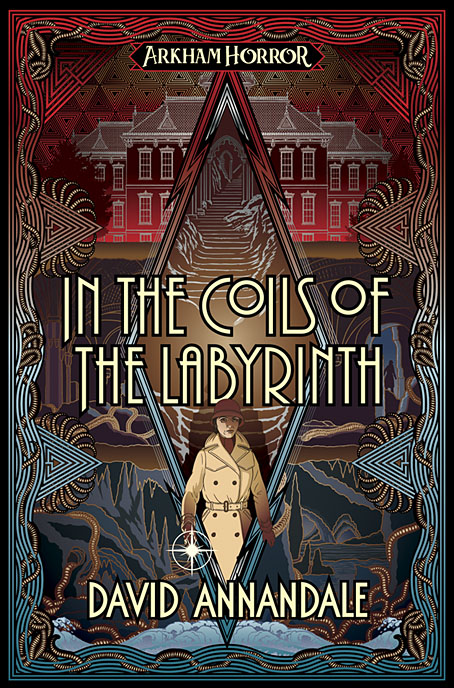

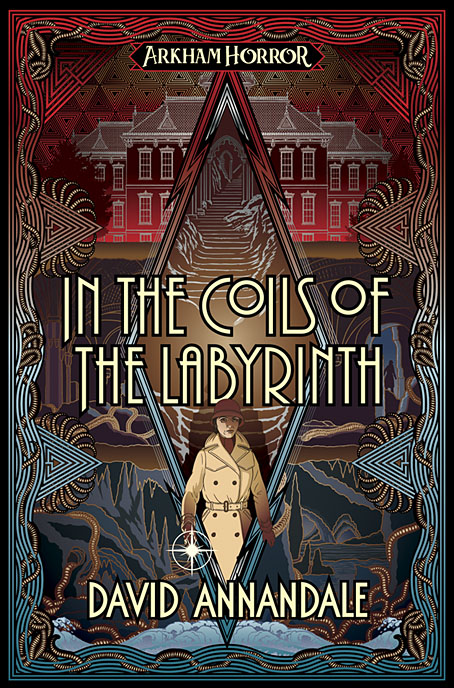

I’ve finally found time to update the website a little so here are the last two book covers I was working on last year. In the Coils of the Labyrinth by David Annandale is another tale of Lovecraftian horror for Aconyte:

Professor Miranda Ventham is having bad dreams—nothing new in 1920s Arkham—but hers are horrifying glimpses of a dark future. Now seriously ill, she books herself into the new sanatorium, Stroud Home. With luck, the town’s eldritch taint won’t reach her there. And yet the nightmares worsen. Aided by her friend, Agatha Crane, they delve into the background of the sanatorium’s enigmatic director, Donovan Stroud. Plagued by doubts, delusions, and terrifying visions, Christine must unravel the shrouded history of the Strouds before she is trapped in a labyrinthine nightmare. Something sinister lurks at its heart, and it longs to be set free.

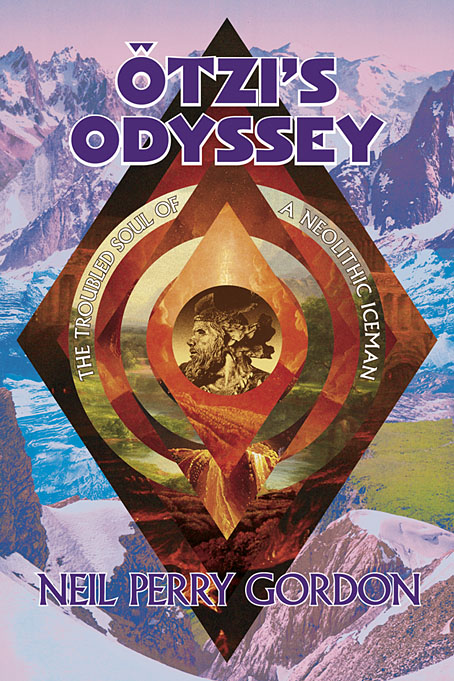

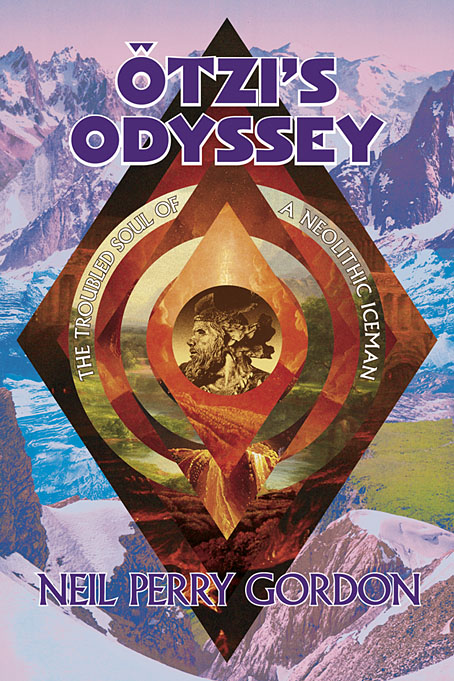

Otzi’s Odyssey by Neil Perry Gordon is a metaphysical drama which posits a fictional life and afterlife for the neolithic iceman whose body was discovered in the Alps:

Ötzi’s Odyssey – The Troubled Soul of a Neolithic Iceman, opens in the year 1991 with the remarkable sighting of a mummified man, half frozen in glacial ice, whom two hikers stumble upon. Along with this profound archeological discovery, the soul of this five-thousand-year-old iceman is awakened.

?Ötzi the iceman’s adventure takes him to the modern era, where his observant soul tries to comprehend why it remains tethered to the frozen mummy, as well as to make sense of a technologically advanced world. The story then returns to 3300 BCE, to the life and times of clan chief Bhark as he lives with his family in a peaceful village upon stilt homes clinging to the shore of the great Lake Neith, located in the shadows of ominous Similaun Mountain.

Both these covers use an elongated diamond shape in their designs, a repetition that I wasn’t intending. I did this first on Otzi’s Odyssey since the story has four infernal realms that the character’s soul travels through. A diamond shape subsequently became necessary for In the Coils of the Labyrinth when a central panel was required that wouldn’t cover too much of the background imagery while also connecting the upper and lower levels and providing a graphic link with my previous covers in this series. There’s a similar shape on my cover for The Voice of the Fire so I should probably avoid doing this for a while…

Still to be announced from last year is an album cover design that I managed to fit in despite several months of serious overwork. This was my first proper album cover for some time (as opposed to the layout I’m usually doing on albums where the artists provide their own art) but the release seems to have been delayed for some reason. More about that one when/if it appears.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Devourer Below

• Litany of Dreams

• The Last Ritual