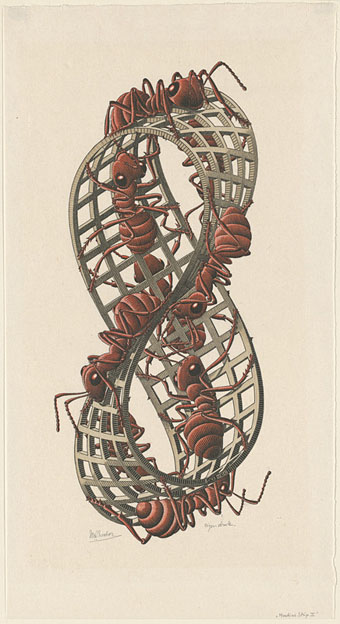

Mobius Strip II (1963) by MC Escher.

• Old music: Warp Records is reissuing two recent Jon Hassell discs later this year: The Living City (Hassell’s ensemble playing live in NYC, 1989) and Psychogeography (Zones Of Feeling) (remixes from City: Works Of Fiction), which will be available as standalone releases or bundled together as Further Fictions together with Hassell’s Atmospherics book.

• “His library is an immense and enviable wellspring, a demimonde of objects by murky creators who for decades have gnawed away at the inner organs of polite society.” Steven Heller talks to Glenn Bray about Library, an 800-page collection of scans from Bray’s trove of books, comics and print ephemera.

• New music: Tsathoggua, the latest in the Lovecraftian series of Cryo Chamber Collaborations which reminds me that I’m still missing the more recent entries. Also the non-Lovecraftian Coil by Ian Boddy.

• “Music is a way to express yourself beyond words,” says Hildur Gudnadóttir.

• See this year’s winners of the annual Close-up Photographer of the Year competition.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…Ishmael Reed The Last Days of Louisiana Red (1974).

• A few new photos of Michael Heizer’s City in the Nevada desert.

• City Of Night (1994) by David Toop & Max Eastley | City As Memory (1995) by John Foxx | City Appearing (2013) by Julia Holter