HP Lovecraft by Virgil Finlay, 1937.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Horror

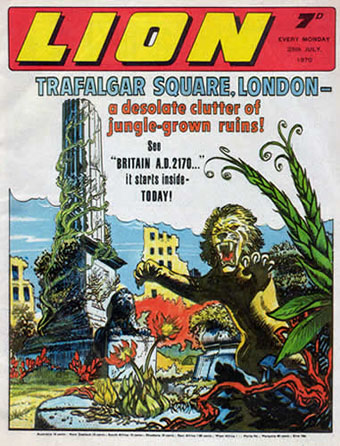

Ballard-for-kids from Lion (1970).

I was never a great hoarder of comics when I was a child, I usually read them then threw them away, so for years I’ve had peculiar half-memories of stories that thrilled me when I was 10-years old but whose titles I’ve invariably forgotten. The web, of course, serves to immediately answer desperately nagging questions such as “Who was the boy in a home-made catsuit climbing all over buildings at night?” (Billy the Cat, and sister Katie), “Which comic did bendable hero Janus Stark appear in?” (Smash and later Valiant), and so on.

British comics nearly always seemed stranger than American ones even though I was a regular reader of Spider-Man and a couple of other Marvel comics. Many of the British adventure titles—all long since expired—were created by artists and writers who drew freely on pulp traditions from the late 19th and early 20th century. Reading through histories of comics such as Lion it’s notable how many of the stories are set in the Victorian era. These tales were invariably hokey and certainly don’t bear much examination now but I can trace later interests back to an early stimulation by these odd strips.

The evil Ezra Creech.

I’m actually surprised to discover that I was a regular reader of Lion, its list of characters is very familiar yet I don’t remember buying a single issue. Lion is significant for being home to one of my favourite strips of the period, the chilling horror/thriller The War of the White Eyes. I’ve yet to meet anyone who remembers reading this which used to be frustrating when I’d pester comic-collecting friends to try and recall which title it appeared in. The story was fairly standard adventure fare from 1972:

The War Of The White Eyes was a US-type fantasy strip which had our heroes, Nick Dexter and Don Redding, trying to thwart the evil megalomaniac, Ezra Creech, who was baying for world domination by inhaling a deadly gas that transformed him into a ‘White-Eyes’, a creature of superhuman strength and ferocity. At first, Creech wanted to destroy our heroes’ home island of Doomcrag and then go on to world domination, but guess who stopped him?

If you live in a place called Doomcrag you’re asking for trouble. I didn’t remember there being a super-villain involved although someone had to be responsible for raining the globes of deadly gas down on the populace.

Creech could turn people into white-eyed zombies under his control. He had superhuman strength as a White Eye. He later developed a ray that allowed him to make things grow, giving him the ability to create monsters.

JMB Chemicals developed a new gas as a mild insecticide. However it proved to have unforeseen side-effects. Men and animals exposed to it were transformed into killers of extraordinary strength and ferocity, recognisable by their white eyes. The first evidence of this came when a few glasses containers of the gas accidentally dropped from the back of a van transporting them through the peaceful English town of Wimbering. Those exposed demonstrated an innate hatred of anyone untainted, and set out to conquer the area and kill “the weaklings”. Even the army proved helpless, with White Eyes ripping apart tanks with their bare hands and throwing them around like toys. Even the White Eyes animals joined in, with contaminated birds attacking troops on the ground. It was only through the bravery and ingenuity of local boys Nick Dexter and Don Redding, and the scientist Timms who had developed the gas in the first place (and also concocted an antidote) that order was restored.

This was very much a horror strip for kids—at least as I remember it—with crazed, white-eyed people and animals going on the rampage, and the ever-present danger that our heroes could be infected themselves. The strip taught me very early on that the simplest way to make someone look evil was to blank out their pupils, something I spent the rest of the decade doing in drawing after drawing.

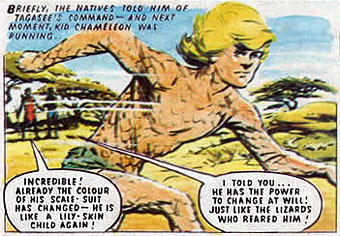

Kid Chameleon takes off.

Another favourite was Kid Chameleon (not to be confused with a later computer game character) whose adventures appeared in my favourite comic of the time, Cor!!:

Stranded in the Kalahari Desert by a plane crash, a British boy is raised by lizards as a feral child, and weaves himself a skin-tight suit of transparent lizard scales which covers his entire body except the top of his head (to avoid the appearance of complete nudity, he also wears a pair of flesh-coloured briefs underneath). Only one strip shows how the suit comes off. It consists of two pieces: a top that opens at the front, and leggings. The suit allows him to camouflage himself like a chameleon by making the scales change colour, although how he does it is never explained.

Yes, I was eagerly reading about a near-naked boy when I was 10; make of that what you will. Kid Chameleon spent two years tracking down the man who caused the plane crash before returning to the desert and the company of the lizards. This strikes me as a very Burroughs-esque idea now, there being plenty of lizard boys and skin suits in Burroughs’ early novels such as The Soft Machine and The Ticket that Exploded. In many ways, Kid Chameleon isn’t far removed from the various incarnations of the Wild Boys—resourceful, shape-shifting and always a loner. By a curious coincidence Burroughs was in London writing Port of Saints, the sequel to The Wild Boys, at the time Cor!! was publishing Kid Chameleon.

There aren’t any pages online from The War of the White Eyes; perhaps that’s for the best, it would only shatter my vague memories even further. However, you can see a couple of pages from Kid Chameleon here, written by Scott Goodall. The strip was drawn by Joe Colquhoun, later the artist on Charlie’s War by Pat Mills.

BBC Radio 3 gets hip to the squamous nightmares of HPL.

Available to listen to online until next Sunday.

Geoff Ward examines the strange life and terrifying world of the man hailed as America’s greatest horror writer since Poe.

During his life Lovecraft’s work was confined to lurid pulp magazines and he died in penury in 1937. Today, however, his writings are considered modern classics and published in prestigious editions.

Among the writers considering his legacy are Neil Gaiman, ST Joshi, Kelly Link, Peter Straub and China Mieville.

French comic artist and illustrator, Philippe Druillet, illustrates British horror novelist William Hope Hodgson. As anyone familiar with Hodgson’s work knows, this kind of imagery predates Pirates of the Caribbean by nearly a century. More pictures here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• War of the Worlds book covers

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Le horreur cosmique

• Davy Jones

Nigel Kneale created reality TV without realising it. Comedian Mark Gatiss recalls his turbulent relationship with the ‘TV colossus’ who died this week.

Nigel Kneale created reality TV without realising it. Comedian Mark Gatiss recalls his turbulent relationship with the ‘TV colossus’ who died this week.

When Big Brother began on Channel 4 in 2000, I took a principled stand against it. “Don’t they know what they’re doing?” I screamed at the TV. “It’s The Year of the Sex Olympics! Nigel Kneale was right!”

In 1968’s The Year of the Sex Olympics, Kneale, a pioneering writer of TV drama who died this week, ingeniously predicted the future of lowest-common-denominator TV. The programme kept a slavering audience pacified with such blackly funny concepts as The Hungry/Angry Show (in which senile old men throw food at one another), the titular Olympics, and the ultimate programme, in which a family are marooned on an island and then watched on camera, 24 hours a day. Yesterday’s satire is today’s reality. Or today’s reality TV.

A few years ago I tried to persuade The South Bank Show to devote an edition to Kneale, only to be told he wasn’t a “big enough figure”. This was doubly dispiriting, not only because, to anyone interested in TV drama, Kneale is a colossus, but because it seemed to confirm all the writer’s gloomy predictions regarding the future of broadcasting. Couldn’t the medium celebrate one of its giants?

Continued here.