Jekyll and Hyde: the queer reading

Not a new idea—Elaine Showalter explored this in her 1991 book Sexual Anarchy—but it’s a compelling interpretation.

Category: {horror}

Horror

My pastiches

Lord Horror: Reverbstorm #3 (1992).

Following from the post about an art forgery exhibition (and Eddie Campbell discussing his American Gothic cover for Bacchus), I thought I’d post some of my own forgeries, or pastiches as we call them when no deception is intended.

Reverbstorm was the Lord Horror comic series I was creating with David Britton for Savoy in the 1990s. The Modernist techniques of collage (as in the work of Picasso and others) and quotation (as in TS Eliot’s The Waste Land) became themes in themselves as the series developed, so it seemed natural to imitate the styles of various artists as we went along. Pastiche is also a chance to flagrantly show off, of course, and I can’t deny that this was also one of my impulses here.

Issue #3 of Reverbstorm had marauding apes as its theme, from the Rue Morgue to Tarzan and King Kong, so I had the idea of doing an ape cover in the style of the celebrated paintings by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527–1593) which make human heads out of fruit, flowers or animals. Easy enough to have the idea but making it work took a lot of effort and required careful sketching beforehand, something I rarely do. The painting was gouache on board, a medium I’d been using for years and this was about the last gouache work I did before switching to acrylics.

Liu Hui Wen’s “The Call of Cthulhu”

Liu Hui Wen’s “Call of Cthulhu”

And other forgotten masterworks of Chinese SF.

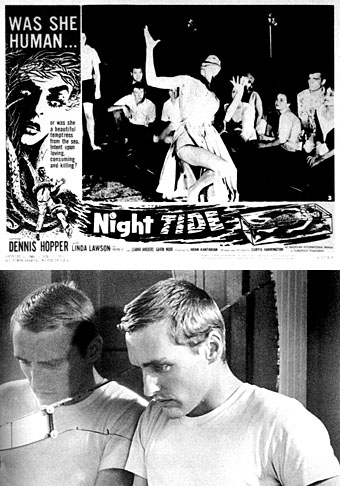

Curtis Harrington, 1926–2007

Curtis Harrington, who died on Monday, was chiefly known as a director of low-budget horror films, the most acclaimed of which is his debut feature Night Tide (1961), a watery riff on Cat People (1942) starring a young Dennis Hopper. But Harrington should also be remembered for his associations with early American avant garde cinema, especially the productions of Kenneth Anger. Harrington was behind the camera for Anger’s Puce Moment (1949) and appeared in front of it as Cesare the Somnambulist in Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954). Harrington’s early films were similarly uncommercial experimental shorts, one of which, The Wormwood Star (1956), was based around the paintings and person of Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel aka Cameron. Harrington and Cameron both appeared in Anger’s Pleasure Dome and Harrington featured Cameron again when he came to make Night Tide, where she appears as a mysterious, witch-like presence.

Night Tide is well worth a look, despite the limitations of its budget. Dennis Hopper had been ostracised from Hollywood after a fall-out with director Henry Hathaway and was hanging around with various artists and experimental filmmakers (including Andy Warhol’s crowd), acting in TV shows and generally biding his time. Harrington gave him a starring role and the opportunity to pull some Method faces, and he’s very impressive as he falls for a girl who may or may not turn into a murderous sea creature with the next full moon. Good use is made of the crumbling beachfront of Venice, CA, and there’s some sly camp humour to be found in Hopper’s appearance (he’s dressed in a sailor uniform most of the time, looking like an extra from Anger’s Fireworks), and in the scene where he goes for a (chaste) massage. Night Tide isn’t as strange as Carnival of Souls (1962) but both films share enough of the same atmosphere and period detail to make a perfect double-bill.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alla Nazimova’s Salomé

• Coming soon: Sea Monsters and Cannibals!

• Freddie Francis, 1917–2007

• The art of Cameron, 1922–1995

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally

Coming soon: Sea Monsters and Cannibals!

No, not Pirates of the Caribbean III although that film will be with us soon and is certain to contain at least one of the above ingredients. The dubious delights of exploitation cinema have been put back on the map recently by Grindhouse, the double feature from Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez, but garish melodrama is nothing new in the film world. Silent films had more than their share of sex, violence, monsters and maniacs, and many featured a degree of nudity that wouldn’t be seen again until the late Sixties, thanks to the Hays Code. “Everything in life is exploitation,” Barbara Stanwyck was told in Baby Face (1933) and she went on to prove it by sleeping her way to the top in a film considered by moral guardians of the time to be so scurrilous that its uncensored print remained buried until 2005.

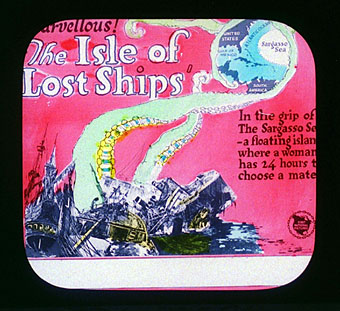

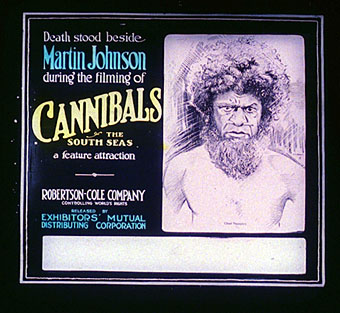

These wonderful hand-tinted plates from the George Eastman archive are lantern slides used to display information about coming attractions, and would have been screened between features as a kind of motionless trailer. The movie trailer as we know it today had been around since about 1910 but it wasn’t until the late Twenties that the regular production and screening of trailers took off. Lantern slides were a cheap way of keeping audiences attentive while the next feature was being prepared.

Cannibals of the South Seas was a 1912 documentary by Osa and Martin E. Johnson and it’s a good bet it was a lot more prosaic than this slide implies. The Isle of Lost Ships seems from the picture to be a sea-faring horror tale but turns out to be a 1923 adventure story based on a novel by one Crittenden Marriott and directed by Maurice Tourneur, father of the great horror and noir director, Jacques Tourneur (Cat People [1942], Out of the Past [1947], Night of the Demon [1957]). This first film is now as lost as the becalmed ships of its title but it was remade as an early talkie in 1929 and that film still exists somewhere. Film remakes are also nothing new. The tentacles and Sargasso setting made me suspect Mr Marriott had purloined an idea or two from William Hope Hodgson, writer of a series of excellent horror stories concerning the Sargasso Sea and (in his fiction) its population of tentacled abominations; Dennis Wheatley certainly stole from Hodgson, as I’ve mentioned before. But Marriott’s novel, The Isle of Dead Ships, and the films based upon it, prove to be less interesting than the slide promises. And so we learn a primary rule of exploitation cinema that was well-established even then: promise much but don’t always deliver.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Seamen in great distress eat one another

• Druillet meets Hodgson

• Rogue’s Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs, and Chanteys

• Davy Jones