Patrick McGrath at Bldgblog

Another great interview covering subjects from Edmund Burke to Ballard and “the new Gothic”.

Category: {horror}

Horror

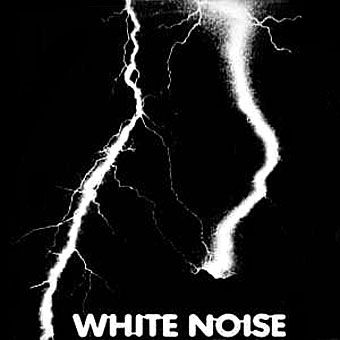

White Noise: Electric Storms, Radiophonics and the Delian Mode

Many sounds have never been heard—by humans: some sound waves you don’t hear—but they reach you. “Storm-stereo” techniques combine singers, instrumentalists and complex electronic sound. The emotional intensity is at a maximum. Sleeve note for An Electric Storm, Island Records, 1969.

An Electric Storm by White Noise is reissued in a remastered edition this week. It’s a work of musical genius and I’m going to tell you why.

Hanging around with metalheads and bikers in the late Seventies meant mostly sitting in smoke-filled bedrooms listening to music while getting stoned. Among the Zeppelin and Sabbath albums in friends’ vinyl collections you’d often find a small selection of records intended to be played when drug-saturation had reached critical mass. These were usually something by Pink Floyd or Virgin-era Tangerine Dream but there were occasionally diamonds hiding in the rough. I first heard The Faust Tapes under these circumstances, introduced facetiously as “the weirdest record ever made” and still a good contender for that description thirty-four years after it was created. One evening someone put on the White Noise album.

It should be noted that I was no stranger to electronic music at this time, I’d been a Kraftwerk fan since I heard the first strains of Autobahn in 1974 and regarded the work of Wendy Carlos, Tangerine Dream, Brian Eno and Isao Tomita as perfectly natural and encouraging musical developments. But An Electric Storm was altogether different. It was strange, very strange; it was weird and creepy and sexy and funny and utterly frightening; in places it could be many of these things all at once. Electronic music in the Seventies was for the most part made by long-hairs with banks of equipment, photographed on their album sleeves preening among stacks of keyboards, Moog modules and Roland systems. You pretty much knew what they were doing and, if you listened to enough records, you eventually began to spot which instruments they were using. There were no pictures on the White Noise sleeve apart from the aggressive lightning flashes on the front. There was no information about the creators beyond their names and that curious line about “the emotional intensity is at a maximum”. And the sounds these people were making was like nothing on earth.

Continue reading “White Noise: Electric Storms, Radiophonics and the Delian Mode”

Wanna see something really scary?

Xeni Jardin and Boing Boing readers reminisce today about the childhood traumas inspired by Sesame Street characters. Wimps, say I, although in fairness I was too old to be frightened of Muppetry by the time that stuff appeared on British TV screens.

Xeni Jardin and Boing Boing readers reminisce today about the childhood traumas inspired by Sesame Street characters. Wimps, say I, although in fairness I was too old to be frightened of Muppetry by the time that stuff appeared on British TV screens.

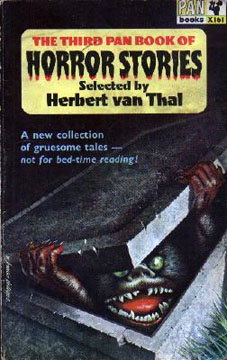

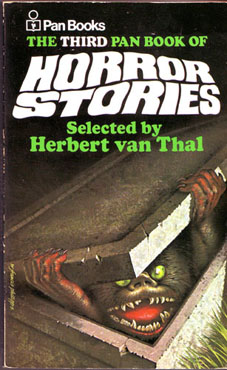

Scariest thing in the Coulthart household, easily out-classing anything on children’s television (Doctor Who monsters included), was the cover of the third Pan Book of Horror Stories. My parents had a small collection of paperbacks from the early Sixties which included some horror and occult fiction. My sister and I found this book one day while rooting in an old suitcase and were both mortified by it. I seem to remember there being dares to go and look at it again and also have vague recollections of at least one nightmare occurring as a result. A shame there isn’t a larger scan available since I’m curious to know who the artist was.

A few years later I was reading the Pan series myself although I never went back to this particular one. Herbert van Thal’s selections got off to a good start, reprinting old horror classics with newer fiction, but soon degenerated into detailed and repetitive tales of dismemberment and blood-letting, the kind of stuff that makes you think “cool” when you’re a teenage boy but which is otherwise worthless. Most of the writers in the later books are unheard of elsewhere which makes me suspect they were probably hacks earning a quick couple of quid writing under pseudonyms. The strangest thing about volume three now is looking at the contents list and seeing that we had stories by William Hope Hodgson and Algernon Blackwood in the house all that time and I never knew it.

A few years later I was reading the Pan series myself although I never went back to this particular one. Herbert van Thal’s selections got off to a good start, reprinting old horror classics with newer fiction, but soon degenerated into detailed and repetitive tales of dismemberment and blood-letting, the kind of stuff that makes you think “cool” when you’re a teenage boy but which is otherwise worthless. Most of the writers in the later books are unheard of elsewhere which makes me suspect they were probably hacks earning a quick couple of quid writing under pseudonyms. The strangest thing about volume three now is looking at the contents list and seeing that we had stories by William Hope Hodgson and Algernon Blackwood in the house all that time and I never knew it.

Update: The cover artist was W Francis Phillips.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Druillet meets Hodgson

• A playlist for Halloween

• Ghost Box

• Le horreur cosmique

The art of Bob Pepper

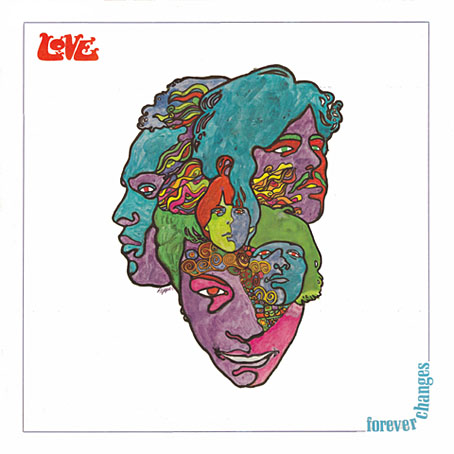

Forever Changes (1967) by Love.

Art by Bob Pepper, design by William S. Harvey.

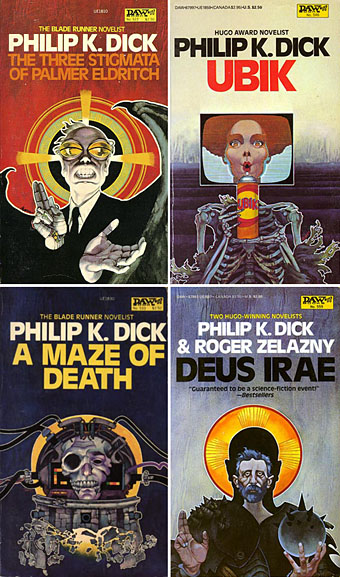

Following yesterday’s post about Philip K Dick covers (and Erik Davis’s appraisal of the DAW cover), I decided to check out Bob Pepper’s work a bit more and it quickly became obvious I should have joined the dots with this particular artist years ago. Pepper’s work not only decorates one of the recognisable record sleeves of the late Sixties (above), he was working shortly afterwards as an illustrator on the celebrated series of fantasy reprints edited by Lin Carter for Ballantine books. Pepper’s connections with Elektra Records also saw him provide sleeve art for some of the eclectic releases on their Nonesuch label. What’s surprising to me now is the realisation that I’d been seeing his work for years in a variety of places and never noticed it was the same artist. Better late than never, I suppose.

Four more Dick covers for a series of six published in 1982 to coincide with the release of Blade Runner. As with the cover for A Scanner Darkly (in the earlier post) these paintings are all portraits.

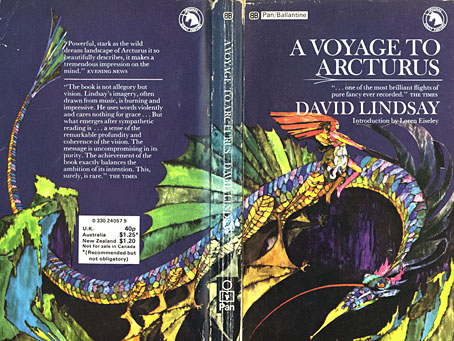

A Voyage to Arcturus (1968) by David Lindsay.

It was the success of the publication of The Lord of the Rings in America which inspired Betty Ballantine to publish a line of fantasy classics in the late Sixties. The series began its run in 1969 and continued until 1974. Lin Carter was commissioned as editor and given free reign to choose any title he thought might be suitable with the result that many of the books in the series—obscurities such as Lud-in-the-mist by Hope Mirrlees—received their first paperback publication. Carter also reprinted personal favourites which frequently shifted from fantasy to outright horror, such as the titles from HP Lovecraft and William Hope Hodgson. The range and scope of this line is what makes the series so notable today and the books have become highly-collectable as a result. Many artists were involved in producing the distinctive cover designs and Pepper’s illustrations were featured on the covers for Mervyn Peake, Lord Dunsany and James Branch Cabell, among others. Unfortunately the various pages devoted to these books aren’t very good at showing the paintings to their best advantage. For a long time Pepper’s cover for A Voyage to Arcturus was one of the few editions available that managed to show a scene from the book, rather than a generic sword-wielding barbarian.

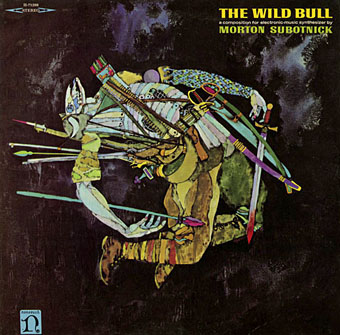

The Wild Bull (1968) by Morton Subotnick.

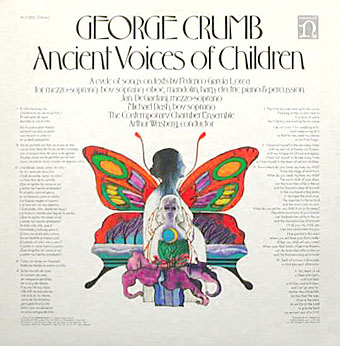

Nonesuch Records was Elektra’s subsidiary classical music label which not only produced classical recordings but also recordings from around the world in their Explorer series, and a range of original works of contemporary electronic music. I’m not positive that the sleeve above is a Pepper painting but it certainly looks like it. This is another surprise since I’ve had Morton Subnotnick‘s album on a reissue CD for years (with different artwork). The George Crumb recording below is Pepper’s work and I’ve had the original vinyl of that one for several years. The similarity between that sleeve and the one for Love is striking.

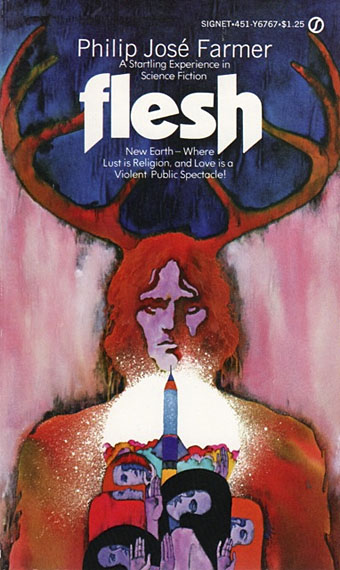

Flesh (1969) by Philip José Farmer.

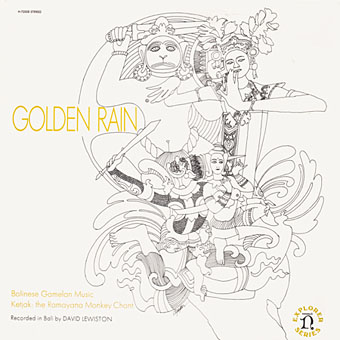

Golden Rain – Balinese Gamelan Music – Ketjak: The Ramayana Monkey Dance (1969) by Various Artists.

Art by Bob Pepper, design by William S. Harvey.

Ancient Voices of Children (1971) by George Crumb.

Art by Bob Pepper, design by Robert W. Zingmark.

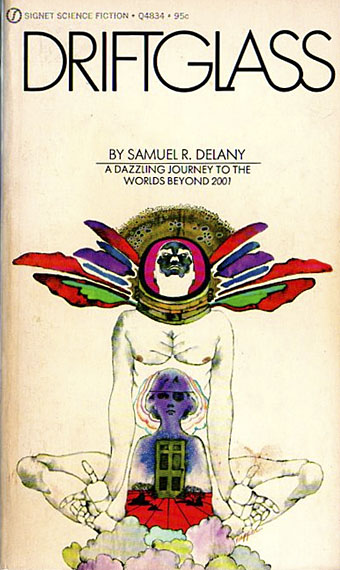

Driftglass (1971) by Samuel R. Delany.

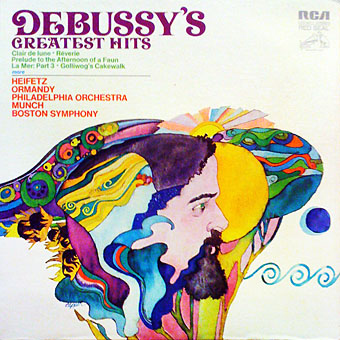

Debussy’s Greatest Hits (1972).

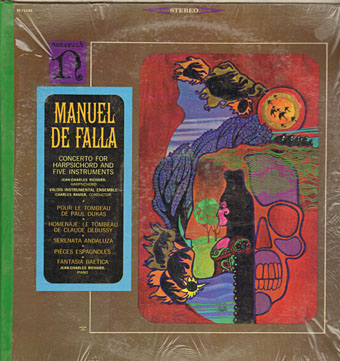

Concerto For Harpsichord And Five Instruments by Manuel De Falla (no date).

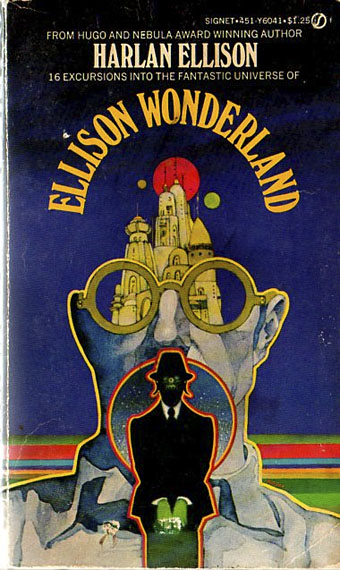

Ellison Wonderland (1974) by Harlan Ellison.

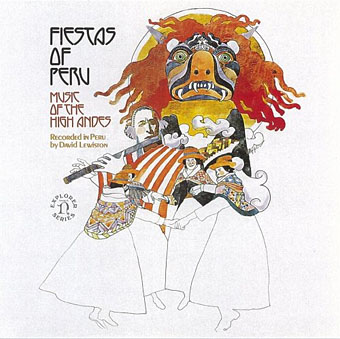

Fiestas of Peru: Music of the High Andes (1975) by Various Artists.

Art by Bob Pepper, design by Jo Ann Gruber.

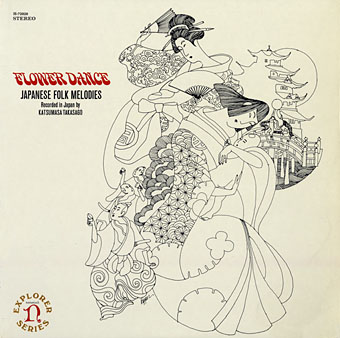

Flower Dance: Japanese Folk Melodies (no date) by Kofu Kikusui, The Noday Family, Nakagawa & Oishi.

Art by Bob Pepper, direction by William S. Harvey, design by Elaine Gongora.

Pepper is retired now but produced artwork for Dark Tower, a fantasy boardgame, in 1981. The game still has its enthusiasts, and this site features a short interview with the artist.

Update: more about the Ballantine covers.

Update 2: a large scan of the George Crumb cover art.

Update 3: More album and book covers added.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton}

• Philip K Dick book covers

• Masonic fonts and the designer’s dark materials

Chiaroscuro

Heavenly Love and Earthly Love by Giovanni Baglione (1602–1603).

Chiaroscuro\, Chia`ro*scu”ro\, Chiaro-oscuro\, Chi*a”ro-os*cu”ro\, n. [It., clear dark.] (a) The arrangement of light and dark parts in a work of art, such as a drawing or painting, whether in monochrome or in colour. (b) The art or practice of so arranging the light and dark parts as to produce a harmonious effect.

Following from the earlier post about shadows in art, some favourite examples by masters of chiaroscuro. Another artist not represented here will be the subject of a post of his own in the next couple of days. The Dutch painter Godfried Schalcken (below) was the subject of the horror tale Schalcken the Painter by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, a story memorably filmed by Leslie Megahey for BBC television in 1979. Horror and the chiaroscuro effect belong together, as Fuseli’s Nightmare demonstrates, and many of Schalcken’s paintings seem even more curious and sinister after you’ve read Le Fanu’s story.

Update: John Klima points us to Hal Duncan‘s excellent story, The Chiaroscurist, which you can read at Electric Velocipede.