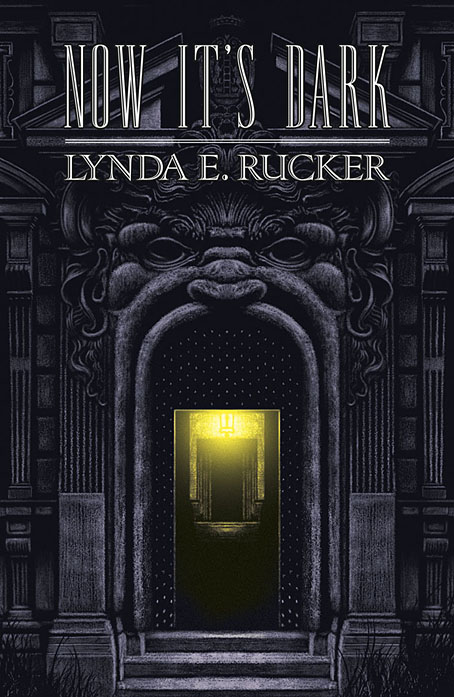

Now It’s Dark by Lynda E. Rucker; cover art by John Coulthart; jacket design by Meggan Kehrli; introduction by Rob Shearman; edited by Brian J. Showers and Timothy J. Jarvis; copyedited by Jim Rockhill; typeset by Steve J. Shaw; published by Swan River Press.

Hardback: Published on 27 January 2023; limited to 400 copies of which 100 were embossed and hand numbered; signed by Lynda E. Rucker, Rob Shearman, and John Coulthart; xii + 225 pages; lithographically printed on 90 gsm paper; dust jacketed; illustrated Wibalin boards; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands; ISBN: 978-1-78380-043-8.

Dust jacket.

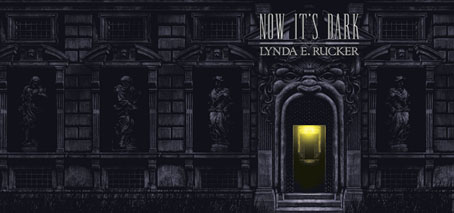

Printed boards.

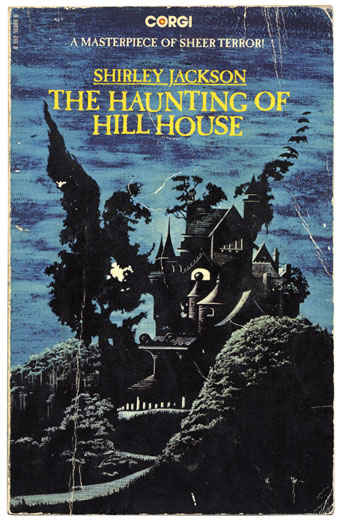

This is the last of the books I was working on last year, and being another design for Swan River Press means that once again the artwork is a wraparound cover with printed boards under the wrap. Now It’s Dark is a collection of horror stories (or possibly “strange stories” à la Robert Aickman), and a very fine collection it is. I was given carte blanche with this one so the cover is a mood piece rather than anything directly illustrational. One of the stories concerns the god Pan, which tempted me at first to do something with a satyr-like face, possibly as an architectural feature like a mascaron. But focusing on a single story in this way usually makes me worry about giving that story too much attention if it hasn’t also provided the title of the collection. Thinking about mascarons and their positioning above arched doorways led to the design you see here, a gesture towards a minor trend in horror illustration that makes use of the Arcimboldo effect, as with my battered Shirley Jackson paperback.

Corgi Books, 1977. No artist credited.

A Boy and His Dog on a Staircase in Rome (1886) by Niels Frederik Schiøttz-Jensen.

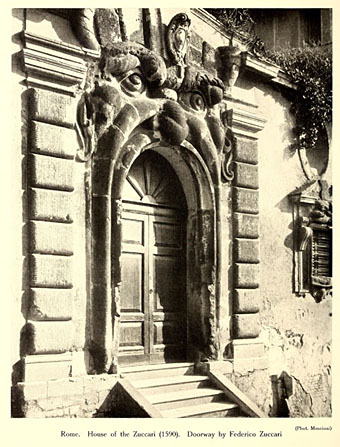

My cover is a variation on a real place, the “House of Monsters” entrance of the Palazzo Zuccari in Rome which today houses the Bibliotheca Hertziana. I placed the portal into an extended Baroque facade while moving the monstrous windows to the boards of the book. Given the way the grotteschi concept was a common feature of the Baroque you’d expect there to be more doorways like this but the palazzo street entrance seems to be unique. Equivalents such as the Ogre’s Head at Bomarzo are more like theme-park attractions than architectural features. I’ve never seen Umberto Eco mention the Palazzo Zuccari but I imagine he would have enjoyed seeing an infernal mouth as an entrance to a library.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Infernal entrances