Catalogue for Art Nouveau Revival 1900 . 1933 . 1966 . 1974. Peacock feather not included.

Regular readers may recall my mention of the Musée d’Orsay exhibition Art Nouveau Revival which was launched late last year. I didn’t get to see the exhibition, unfortunately, but this week I finally ordered a copy of the catalogue, an expensive cloth-bound volume with essays (in French) by Philippe Thiébaut, Stephen Calloway, Irene de Guttry, Thierry Taittinger and Philippe Thieryre. Despite the ruinous postal charges incurred by the book’s weight this was worth every euro, it being the kind of polymorphous production which in solipsistic moments one can choose to believe was created solely for your own benefit.

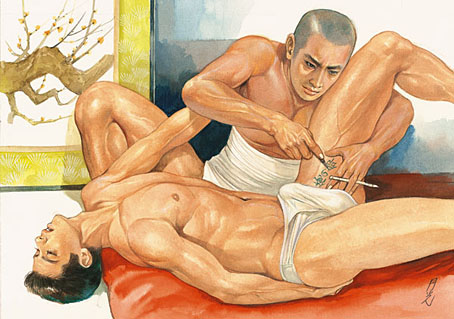

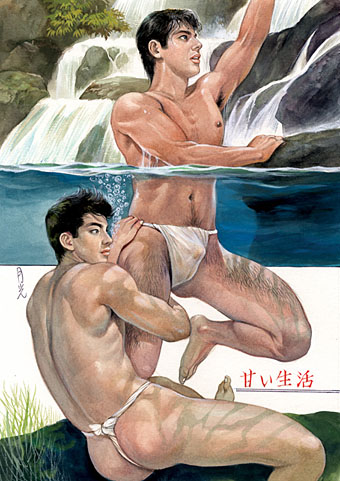

Aubrey again, album covers from 1974.

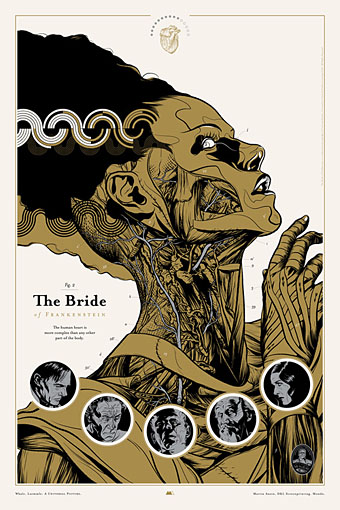

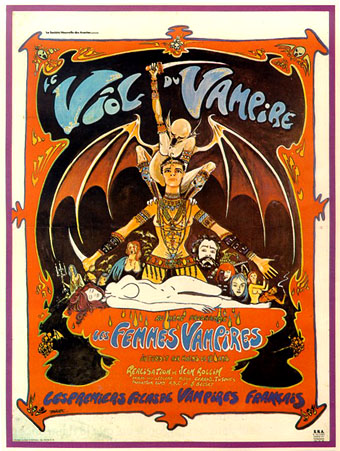

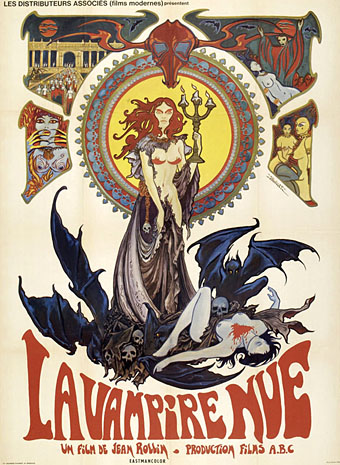

Much of the subject matter has been explored here in various small ways, with the curators following the influence of Art Nouveau through Surrealism (mainly Dalí) to the psychedelic art of the 1960s and on into the Pop Nouveau (for want of a better term) which flourished in the first half of the 1970s. Among the familiar Aubrey Beardsley graphics and psychedelic posters there are also some pleasantly surprising inclusions, including illustrations by Philippe Jullian (yes, I’m still intending on writing about him at some point), yet more Beardsley album covers, film posters, and even some of the sillier films of the late-60s such as Casino Royale. Being a French exhibition there’s a section devoted to comic strips which includes work by Moebius, Philippe Druillet and Guido Crepax.

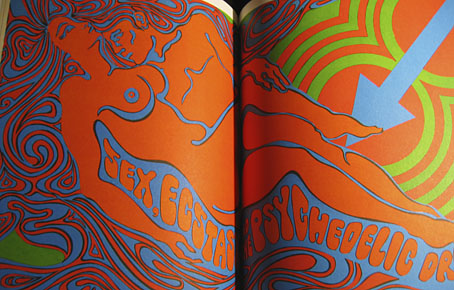

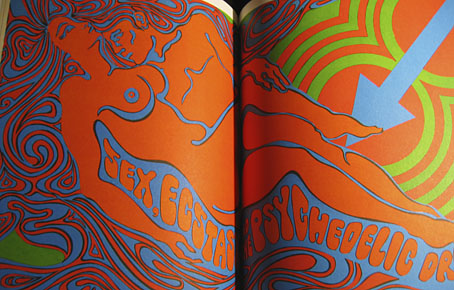

Sex and LSD, a spread from Playboy, 1967.

It’s common to see parallels drawn between the 1890s and the 1960s but the strange blooms of vulgarised fin de siècle style which burgeoned in the wake of psychedelia are seldom given much attention. One of the great things about this catalogue is the amount of ephemera the curators chose to include such as magazine ads and trend-chasing album sleeves. It was precisely this blend of 1890s + 1960s + 1970s I sought to capture in my recent cover for Dodgem Logic. As I said, it’s an expensive book but for anyone drawn to this aesthetic hothouse it’s also an essential purchase. Art Nouveau Revival can be ordered direct from the museum shop. Further samples follow.

Continue reading “The Art Nouveau dance goes on forever”