Bluebeard (1982) by János Kass.

I thought I might not be able to do a fresh playlist this year, so much has already been covered by the previous lists (see the links below to earlier posts).

The search for new tonalities and timbres in 20th-century orchestral music led many composers to produce works that sound like—and have been used as—horror film soundtracks although you’ll never find critical discussion acknowledging such a vulgar reaction. This is a very masculine list although some of the performers are women. I might have included Diamanda Galás but she was in the first list, as was Delia Derbyshire with her associates in White Noise, the subject of a longer post here.

The Isle of the Dead (1909) by Sergei Rachmaninov

Mentioned here a few days ago, Rachmaninov’s suitably sombre piece is one of many compositions to borrow the medieval Dies Irae hymn for one of its themes.

Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) by Béla Bartók

Frank Zappa once said that his initial response upon hearing the music of Edgard Varèse was “These chords are mean; I like these chords.” I feel the same about Bartók’s music which can get very mean indeed. The obvious piece to mention would be the Adagio from Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste which Stanley Kubrick used in The Shining. Instead I’ve selected Bartók’s only opera, a psychodrama for two performers and orchestra in which Bluebeard’s new wife, Judith, explores the castle (which also represents her husband’s character) only to find everything there stained with blood.

Visage (1961) by Luciano Berio

In which Berio records his wife and frequent collaborator, Cathy Berberian, then dissects her vocalisations to disturbing effect. “Visage contains no singing, and virtually no words,” says Martin Butler. “The product of days of gruelling recording for Berberian (leaving her physically damaged), it instead consists of her laughter, moans and groans, snorts and wheezes, and gibberish, all brilliantly edited, filtered, distorted and mixed with electronic backing. It is a remarkable demonstration of the power of the wordless voice. The effect is shocking and extreme, but also hilarious and touching – and often all these things simultaneously.”

Bohor (1962) by Iannis Xenakis

In addition to making some of the most thrilling and advanced new music of the 20th century, Xenakis chose great titles for his compositions, frequently unusual words. Bohor is a recording of layered sound sources that include a Laotian mouth organ, prepared piano, Iraqi and Hindu jewellery, and should ideally be heard with the sounds surrounding the listener. Intended by its composer to represent “the onset of madness”.

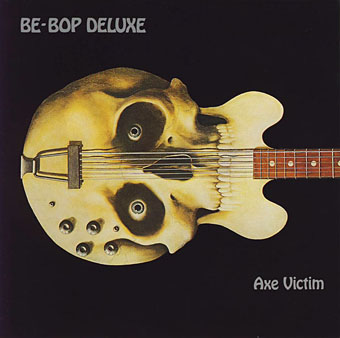

Design by Paula Bisacca.

Uaxuctum: The Legend of the Maya City, Destroyed by Themselves for Religious Reasons (1966) by Giacinto Scelsi

And speaking of great titles… The Italian composer uses orchestra, a choir and an Ondes Martenot to convey an ancient apocalypse. Part III was selected by Robbie Robertson (along with works by other composers listed here) for the Shutter Island soundtrack.

Lontano (1967) by György Ligeti

Stanley Kubrick used Ligeti’s music in three of his films. Lontano‘s piercing harmonics and growling chords prowl through The Shining together with pieces by Bartók and Penderecki.

Black Angels: Thirteen Images from the Dark Land (1970) by George Crumb

Many of the pieces here jangle the nerves but none more than Crumb’s composition for string quartet, glass and metal instruments, a part of which is used in The Exorcist. Composed “in time of war”, it’s a howl of despair whose opening manages to be even more disturbing than Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. The 1990 Kronos Quartet recording is essential.

Logos (Rituel Sonore) (1970) by Igor Wakhévitch

“Sound ritual for pop group, mixed choir and magnetic tape.” The first album by the elusive French composer, a composition for a ballet, described by Alan Freeman as “a soprano singer, strange orchestral textures and percussives (drums, cymbals, gongs, etc.) blended with effects and processing. As the ominous percussion sets off with drum-rolls and ritualistic tension, the mood is of a looming anticipation of what is to come. Here we go through phases of weird swirling effects, vivid reverb and atmosphere. The tension becomes overpowering, yet we are led on…”

The Dream of Jacob (1974) by Krzysztof Penderecki

The Polish composer wrote for film soundtracks as well as the concert hall so it’s no surprise that his work can be heard in The Exorcist, The Shining and Shutter Island. The atmosphere of sustained malevolence in this piece is perfect for Kubrick’s haunted house. Whatever Jacob was dreaming about, it wasn’t pleasant.

Design by Heung-Heung Chin.

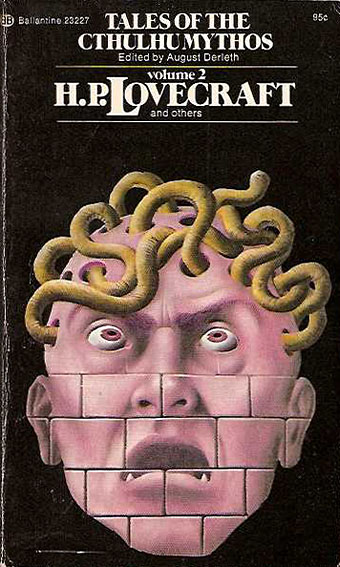

Necronomicon (2004) by John Zorn

A five-part composition for string quartet from Zorn’s Magick album.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Powell’s Bluebeard

• A playlist for Halloween: Drones and atmospheres

• A playlist for Halloween: Voodoo!

• Dead on the Dancefloor

• Another playlist for Halloween

• A playlist for Halloween

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch