Gahan Wilson’s macabre humour has provided stories for film and television on a number of occasions but this very short entry is the only one I’ve seen so far. Gahan Wilson’s Diner seems closest to Wilson’s work as a cartoonist, being an attempt to faithfully translate the style of his drawings and their grotesque predicaments to the world of animation. Wilson wrote and designed the film, the direction is credited to Graham Morris and Karen Peterson. Watch it here.

Category: {horror}

Horror

Weekend links 775

The Bride of the Wind (1914) by Oskar Kokoschka.

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Fantômas, by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain (translated by Cranstoun Metcalfe).

• This week’s Bumper Book of Magic news: the Brazilian edition of the book, titled A Lua e a Serpente: Almanaque de Magia, will be published in June. It’s available for pre-order here.

• “The basis of compilations as far as I’m concerned is, ‘I like this stuff, you may like it too.’” Jon Savage on the art of the compilation album.

• At Public Domain Review: The strange story of Oskar Kokoschka, Hermine Moos, and the Alma Mahler Doll.

• At the Daily Heller: Psychedelics, Day-Glo, Hallmark and The Peculiar Manicule.

• Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine, a new version for sale from Important Records.

• The Strange World of…Michael Chapman.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Boris Karloff Day.

• RIP David Thomas of Pere Ubu.

• Dream Machine (1968) by Les Sauterelles | Dream Machine (1980) by The Androids | Dream Machine (1981) by Phantom Band

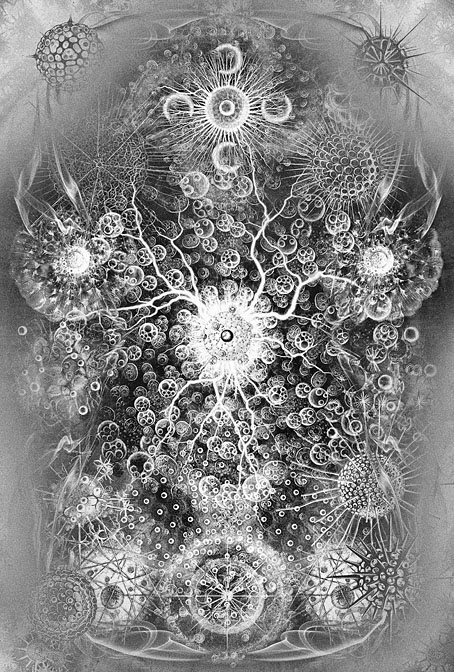

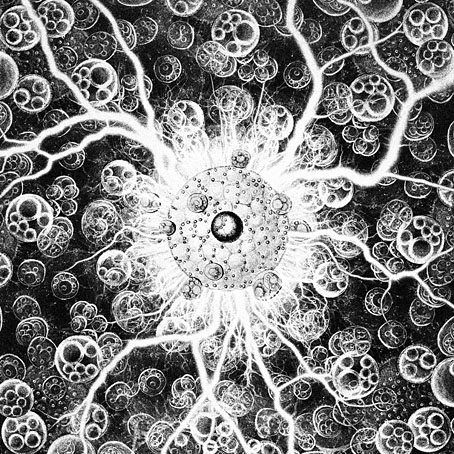

Kadath and Yog-Sothoth

Last month I posted an updated version of the Yuggoth collage I created in 1994 for the Starry Wisdom story collection. I didn’t mention at the time that one purpose of the reworking was to freshen the piece for a more ambitious updating of my own Lovecraft book, The Haunter of the Dark, a volume which has now been through two different editions. I’m generally resistant to the temptation to tamper with old artwork, something which is always present when you’re using digital tools. I’d much rather create something new. In the case of The Haunter of the Dark, however, this has felt necessary when the plan for the new edition requires adding a quantity of my more recent Lovecraft-related pieces to the older art. The section of the book titled The Great Old Ones was a collaboration with Alan Moore in which deities and locations from the Cthulhu Mythos were mapped across the Sephiroth of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Most of the art for this section was done in 1999 when I’d only been using Photoshop for a couple of years. I was excited by the possibilities the software presented but some of the results look very typical of the period: lots of obvious filtering, and transparent layering of a kind I seldom do today. Since I finished reworking the Yuggoth collage (which happens to be a part of The Great Old Ones section) I’ve also reworked three more pieces: Nyarlathotep, Kadath and Yog-Sothoth. The latter two you see here, Nyarlathotep isn’t quite finished yet. My intention with the new versions has been to retain the idea, and in some cases the composition, of the original, while creating a new piece which avoids the shortcomings of the 1999 versions.

Kadath, 2025.

Of the two, the original Kadath was a piece I was never happy with. I hadn’t thought very much about how to represent Kadath beyond having a cluster of buildings in a snowy setting. Lovecraft is evasive about the details but the place is essentially a fantastic palace (or maybe a city) in an icy wasteland. My original version collaged together bits of Indian, Thai and Cambodian architecture which created a definite “exotic” appearance but I was never happy about using identifiable temples in this way. The composition was also rather messy. The new piece also takes the collage route, only this time I’ve used architectural details from some of the pavilions built for the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900. Several of the themed pavilions built for the exposition were fanciful and fantastic extrapolations of the Beaux-Arts style that don’t resemble anything built before or after. The buildings were also temporary constructions so they’re a lot less identifiable than buildings with a longer history.

As for Yog-Sothoth, this one follows the idea of the original but with better choice of elements and presentation. Once again, details are vague as to Yog-Sothoth’s appearance but I always come back to the description of an inter-dimensional mass of spheres or globes. The original illustration manifested these globes by swiping a variety of globular creatures from Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur, something that worked quite well but the composition could have been better. The new picture follows suit, only this time I’ve borrowed details from another Haeckel book, Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda radiaria): Eine Monographie (1862), which is less well-known and with illustrations of many more globular or radial organisms than in the other volume.

For the remaining pieces I’m going to be drawing rather than collaging. The results will be posted here in due course.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Weekend links 760

Ermitaño Meditando (1955) by Remedios Varo.

• Public Domain Review announces the Public Domain Image Archive. I’ve added it to the list. Meanwhile, the PDR regular postings include Francis Picabia’s 391 magazine (1917–1924).

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Well at the World’s End by William Morris.

• At Smithsonian Magazine: “See 25 incredible images from the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Contest”.

The ideas are more complex than the presentation suggests, but not vastly. Neither is it exactly breaking new ground. Art is everywhere, they say, from fingernails to fine dining; art is not a message to be decoded, but takes on new meanings in the mind of each viewer; art allows us to experience emotions in a “safe” context, like a form of affective practice; art helps us to imagine new worlds, thereby expanding the boundaries of what’s possible in the real world. The point isn’t to be original, though, but to distil a lifetime’s worth of practical wisdom and reflection. The result is a kind of joyous manifesto: just the thing to inspire a teenager (or adult) into a new creative phase. Eno and Adriaanse conclude with a “Wish”: that the book helps us understand that “what we need is already inside us”, and that “art – playing and feeling – is a way of discovering it”.

Brian Eno and Bette Adriaanse talking to David Shariatmadari about their new book, What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory

• “Crunchie: The Taste Bomb!” DJ Food unearths four psychedelic posters promoting Fry’s Crunchie bars.

• New music: Music For Alien Temples by Various Artists, and Awakening The Ancestors by Nomad Tree.

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine lays out a history of the Tarot in England.

• Sun Ra & His Intergalactic Research Arkestra live on German TV, 1970.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Chris Marker Day (restored/expanded).

• At the BFI: Anton Bitel on 10 great Mexican horror films.

• Matt Berry’s favourite albums.

• Tarot (Ace of Wands Theme) (1970) by Andrew Bown | Tarotplane (1971) by Captain Beefheart And His Magic Band | Tarot One (2012) by Tarot Twilight

02025

Dance of Flames (1925) by Hayami Gyoshu.

Happy new year. 02025? Read this.

Oben und Links (1925) by Wassily Kandinsky.

Aus Torbole (1925) by Stephanie Hollenstein.

Coronilla (1925) by Paul Nash.

Demonstration (1925) by Franz Wilhelm Seiwert.