Category: {gay}

Gay

The Picture of Dorian Gray II

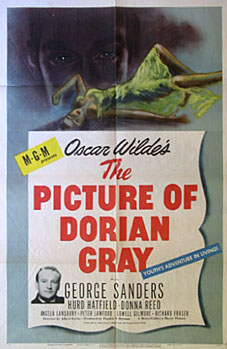

Oscar Wilde’s novel was filmed by Albert Lewin in 1945, a great adaptation with Hurd Hatfield playing Dorian, George Sanders as the aphoristic Lord Henry and Angela Lansbury as Sybil Vane. Lewin made a number of respectably arty films during the Forties and Fifties but Dorian Gray has always seemed the best to me, even if I am biased towards the story.

The film was shot in black and white but views of the painting were shown in colour. For the final view of Dorian’s decayed portrait he commissioned the hyper-real artist Ivan Albright (1897–1983) whose shockingly grotesque picture (below) provides a memorable climax to the film. That painting now resides in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Update: added a “before” view of the painting.

Update 2: added a link to a recent Wikipedia copy of the “after” picture that’s larger than previously available versions.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive

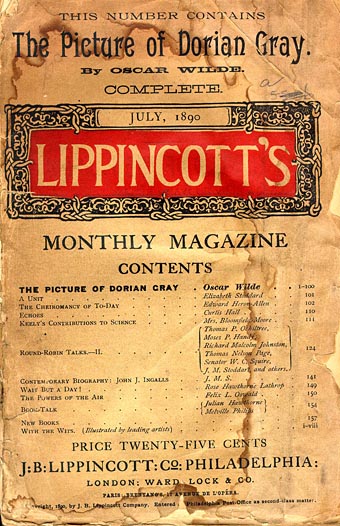

The Picture of Dorian Gray I

The original magazine publication, 1890.

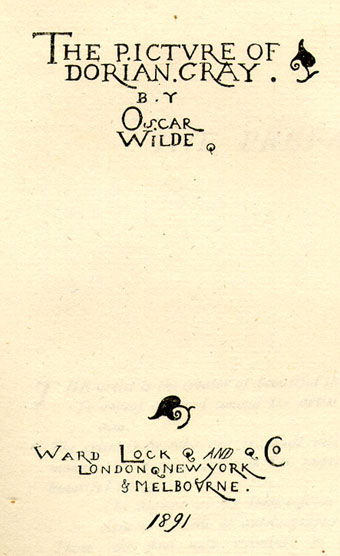

Title page of the first edition, 1891.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive

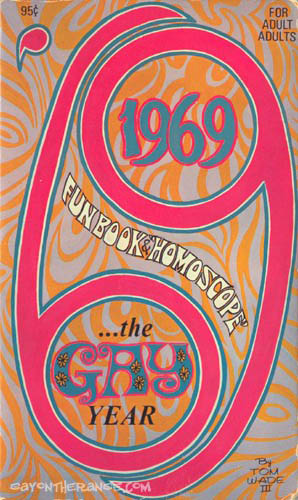

Gay book covers

Gay on the Range (very apt name in the year of Brokeback Mountain) has a great selection of gay paperback covers from the 1950s and 60s. The one above is one of the more psychedelic examples (I was 7 years old in 1969; no one told me it was “the gay year”.) Lots of hysterical art and titles, some of them genre parodies, others delicious examples of steamy prurience that teasingly imply “exposure” of the terrible world of “the gay”. For balance, the Strange Sisters site has a similar collection of lesbian book jackets from the same period.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The book covers archive