The Maids murder mystery

Neil Bartlett’s new production of Genet.

Category: {gay}

Gay

The recurrent pose 3

It’s that man again… Another instance of the perennial Flandrin pose, this time from photographer MJ Cardozo. The earlier examples are linked below.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The recurrent pose archive

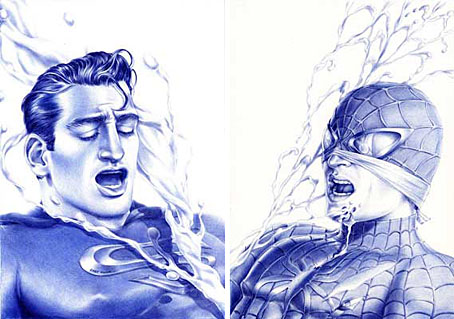

The art of ejaculation

left: Sperman (2007) by Cary Kwok; right: Here Cums the Spider (2007) by Cary Kwok.

NSFW, as if you need to be told. It’s almost a commonplace of contemporary art that there are so many artists around today, producing such a volume of work, that any newcomer (as it were) has to find a niche and stay there if they want their efforts to stand out from the crowd. Cary Kwok’s niche seems to be the seminal emission which he depicts in a variety of ways, including showing various well-known comic-book characters shooting their respective loads. Kwok’s work has been shown recently at the Herald Street gallery, London, and Hard Hat, Geneva.

I like Kwok’s drawings, they’re carefully-done and funny, and serve to remind one that the cum shot is under-represented in art. Despite various Biblical prohibitions, women have been subject to no end of sexual display throughout art history, from copulations with gods in the form of animals to Danaë’s impregnation by Zeus as a literal golden shower. But male sexuality, especially at its most essential moment, has rarely been depicted outside the pages of pornography. The irony of this, as with arguments against erections in art, is that if it wasn’t for ejaculations we wouldn’t be here to discuss their pros and cons. Gay artists have been in the vanguard of addressing the sperm-drought, possibly because they have more than a passing interest in these matters; Michael Petry’s work earlier this year took a lateral view. There’s another sample (as it were) of Cary Kwok’s work below the fold plus some other seminal (as it were) artworks through the ages.

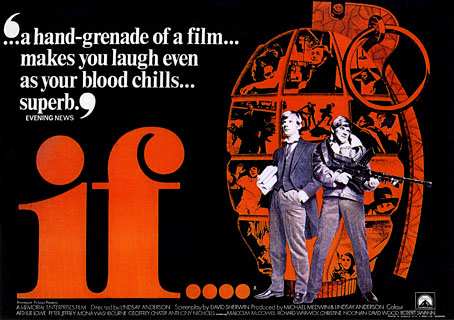

If….

Lindsay Anderson‘s masterpiece, If…., is finally given a DVD release in the UK in June. Anderson’s film—the dramatic resistance to authority by three boys at an unnamed British school—was made in 1968 but I didn’t get to see it until (as I recall) 1977. I was 15 at the time and feeling increasingly desperate and hidebound by school-life so this film was explosive in its psychological impact as well as its story (that grenade on the poster was very apt). Given my age and the year, I’m supposed to have cult yearnings toward the wretched Star Wars but it was If…. that made the lasting impression.

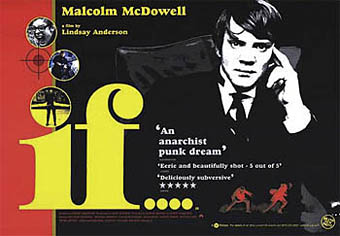

Poster for the 2002 re-release.

If…. was important for a number of reasons, not all of them obvious during that first viewing. I didn’t go to an all-boys public school (note for Americans: “public school” in Britain actually means an expensive, private establishment) but my grammar school had been an all-boys place a few years before I arrived. Some teachers wore gowns at assembly and many of the older teachers there were of a rigid, brutalist mindset exactly like the ones in Anderson’s film. Bullying was endemic, uniform rules were enforced to a degree that would make an army colonel proud and you stood out from the crowd at your peril; I had friends there but I hated every minute. So here comes young Malcolm McDowell on the television screen, effortlessly charismatic and insouciant in his first film role, portraying the ultimate Luciferan rebel, one who (as Anderson writes in the screenplay preface below) says “No” in the face of overwhelming odds. Reader, I identified so very much…. The famous ending (borrowed from Jean Vigo’s Zéro de Conduite) where Mick and the other “Crusaders” fire guns and throw grenades at the rest of the school was headily wish-fulfilling. (And given recent events, you’ll also see below that Anderson and screenwriter David Sherwin regarded that ending as metaphorical, not literal.)

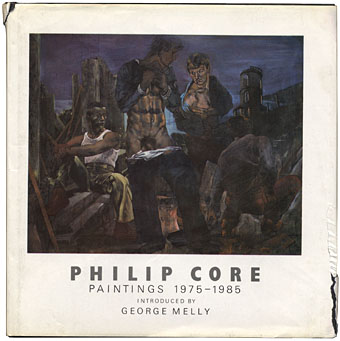

Philip Core and George Quaintance

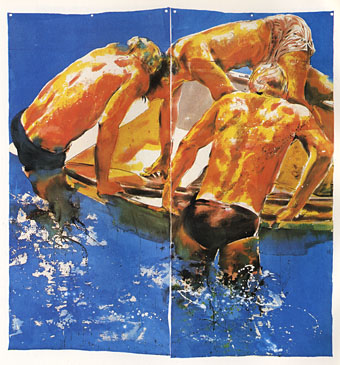

A solidly gay day for secondhand books with the discovery of two relatively scarce items by gay artists. Philip Core is probably more well-known as a writer than a painter, author of The Original Eye: Arbiters of Twentieth Century Taste and the masterful Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (both 1984 and both out of print, unfortunately). His paintings predominantly feature unclothed men but present these in a far more painterly style than one usually sees from gay artists, the approach too often being a kind of kitsch photo-realism that tends towards soft (or hard) porn. A shame that this volume is rather battered as it seems to be a rare book. Core died of AIDS in 1989 but his paintings are still being bought and sold, gay art being one genre that never lacks for an audience.

The Bermuda Triangle by Philip Core (1982).