The Cruz bus flaunts its giant flag.

It’s that time of year again as Manchester gives over its city centre to the flamboyant hordes. I was surprised that the afternoon weather—which has been singularly dismal this year—managed to be bright and even slightly warm while the Parade was in progress. Yes it’s August but this summer has seen temperatures struggle to rise above 17ºC and we’ve had continual rain.

The Canal Street throng.

After the Parade the Gay Village streets were insanely crowded, too much so, it was impossible to move much of the time. That aside, there was a good atmosphere as there always is in gay crowds. (Or is that just my bias?) Roisin Murphy is playing the main stage on Sunday evening so I may stick around if the weather holds. As I type this it’s raining heavily—again.

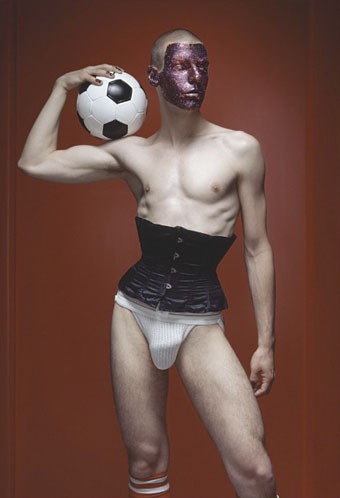

Numerous drag queens in evidence. And a shirtless guy on stilts…

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Over the rainbow

• London Pride

• São Paulo Pride 2006