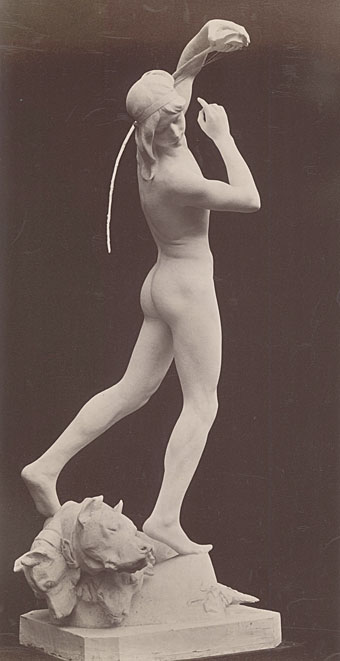

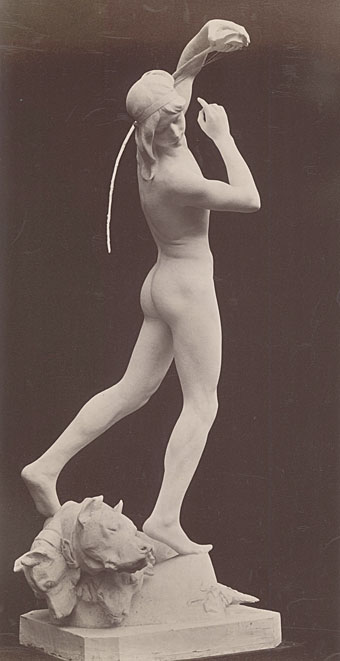

Orphée endormant Cerbère by Henri Peinte (1887).

It’s often difficult to imagine a perfectly innocent motive when looking at works such as these. Did the world really need another statue of Orpheus or is the true intention revealed by those carefully sculpted buttocks, with the mythology added as a convenient subterfuge? We’ll never know, of course, and that’s part of the fun. Orpheus, Narcissus, Icarus and the rest gave 19th century sculptors and painters the excuse to portray unclad men and youths in a manner which would have been highly suspect—scandalous, even—had the subjects been shown in a contemporary context. In Oscar Wilde’s definition, art reflects the spectator; in Philip Core’s definition, camp is a lie which tells the truth. Camp art, therefore, can tell a truth about the artist whilst reflecting the concerns of the spectator. As it turns out, this work by Henri Peinte (1845–1912) had its delights, camp or otherwise, concealed by a prudish sheet of cloth when cast in bronze, a common fate of reproductions intended for home display.

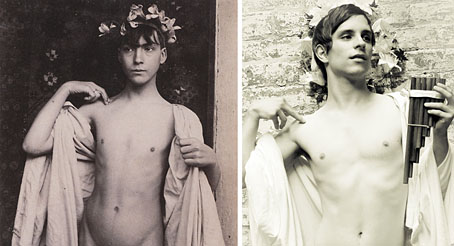

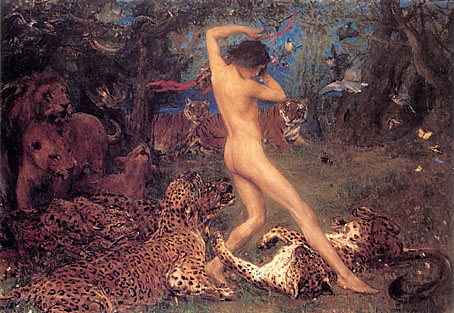

Orpheus by John Macallan Swan (1896).

The Encyclopaedia Orphica collects many of the numerous representations of Orpheus, including this equally lithe depiction by John Macallan Swan (1847–1910) with a pose reminiscent of Peinte’s sculpture. Swan’s painting of the poet charming the savage beasts combines two of his recurrent themes, wild cats and unclothed males. Was he another Uranian with a camp sensibility or is this mere academic innocence? Whatever the answer it’s easy to see why Jean Cocteau—who once said “I am a lie that tells the truth”—made Orpheus his pagan saint.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Antonin Mercié’s David

• Reflections of Narcissus

• Narcissus

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau