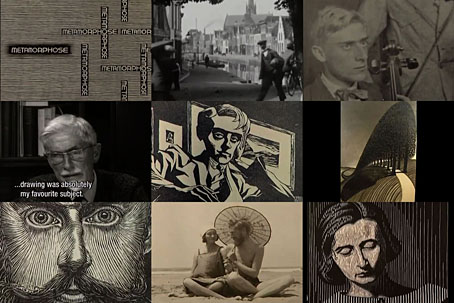

This is a Dutch documentary with narration in English, made in 1998 for the centenary of MC Escher’s birth. Unlike other films about the artist which examine the famous tessellated patterns and visual paradoxes the approach here is a strictly biographical one. Being a Dutch production, the producers had access to a large quantity of material about Escher’s life: photographs, diaries, sketches and so on, which means we learn a lot about his early years and his subsequent travels in Italy. The film seeks out some of the places that Escher drew in the 1920s, the tiny southern towns whose architecture would turn up decades later in many of his well-known prints. There’s also a visit to the Alhambra in Spain where Escher not only sketched the architecture but also made copies of the tile patterns. Best of all is footage of the artist himself in the 1960s talking about his work, together with extracts from other films that show him pulling prints from his engravings.

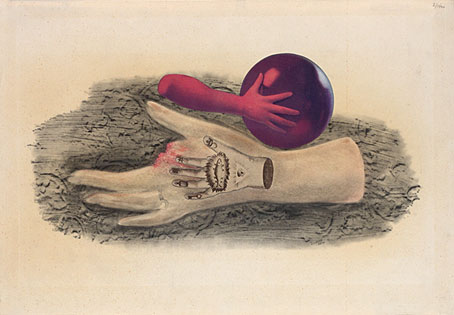

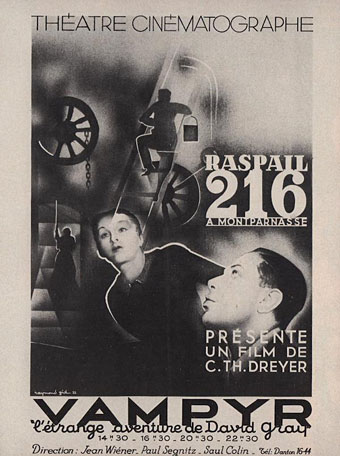

What we don’t have is any indication as to how an artist who was struggling to make a living for at least half his career suddenly came to find his work featured in TIME magazine in the 1950s. Expert commentary in documentaries can sometimes seem superfluous but this is a film that would have benefited from the contribution of someone like Bruno Ernst whose Magic Mirror of MC Escher is an excellent study of the artist’s working methods and the thinking behind them. The film alludes to the growing popularity of Escher’s prints in the 1960s but there’s no mention of this being fuelled in part by illicit reprinting. While scientists and mathematicians were decorating their offices with bona fide Escher prints, their drug-taking students were doing the same in their dorm rooms with bootleg blacklight posters. Escher wasn’t impressed by the hippies, and showed little interest in the art world; there’s a brief mention of Dadaism in a reading from one of his letters but we’re not told what he thought of the Dadaists, or of the Surrealists who would seem like his natural allies, Magritte especially. (Escher’s Castle in the Air woodcut from 1928 was made 31 years before Magritte’s Castle of the Pyrenees.) Art critics reciprocated by ignoring Escher until his popularity made the avoidance unsustainable, after which the default position was to dismiss him as too “tricky” or coldly cerebral. Escher’s outsider status is almost unique in 20th-century art, and warrants a mention at least. Caveats aside, Metamorphose is still worth seeing, especially if you only know the artist from his later works. Watch it here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More swans and robots

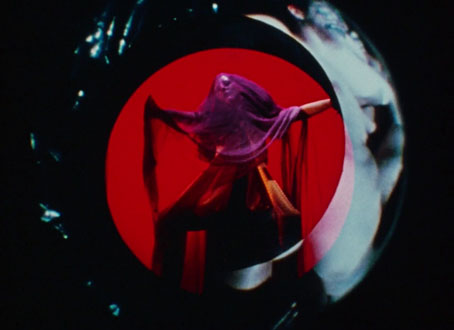

• Suspiria details

• MC Escher book covers

• Relativity

• Escher’s snakes

• The Fantastic World of MC Escher

• MC Escher album covers

• Escher and Schrofer