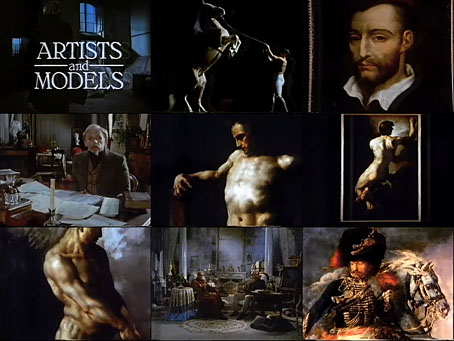

Yes, I’ve been watching a lot of films about art recently, and here’s another one. Artists and Models was the series title for three 80-minute drama-documentaries broadcast by the BBC in 1986: The Passing Show, Slaves of Fashion, and Men and Wild Horses. The writer and director of all three productions was Leslie Megahey, a name I always looked out for in TV listings throughout the 1980s, and still do in the case of films such as these. I watched the series at the time, and taped the episode about Géricault but the tape went astray many years ago so it’s great to find again.

Art, especially painting, was a recurrent theme in Megahey’s work going back to the 1960s. In his later films he combined this interest with careful period recreations, the most celebrated example of which is his superb supernatural drama, Schalcken the Painter, an adaptation of the Sheridan Le Fanu ghost story. Artists and Models favours art history over drama, being an examination of the connected careers of three French painters of the late-18th and early-19th centuries: Jacques-Louis David, the Neoclassicist who was probably the only artist in history to sign the execution warrants of his own king and queen; Jean-Auguste Ingres, the Academician and painter of sensual nudes; and Théodore Géricault, the gloomiest of all the French Romantic artists. Being partial to the Romantics, especially the gloomy ones, I was always going to be more interested in the Géricault film. But all three films are worth seeing, each depicting an aspect of French art during a time of great historical upheaval: state propaganda (David), meticulous Orientalism (Ingres), and tormented realism (Géricault).

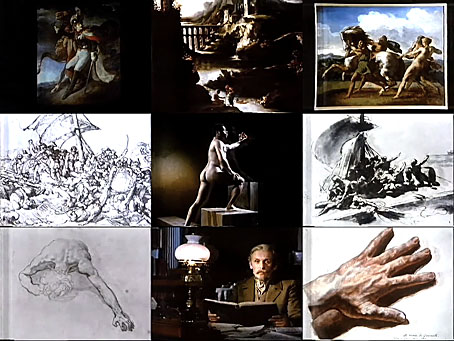

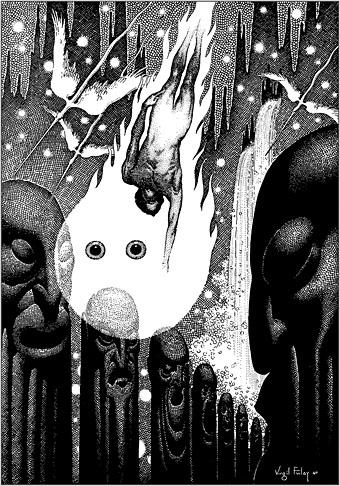

The Raft of the Medusa (1819). All photo reproductions of this painting are compromised by the bitumen that Géricault painted into the shadows, a substance that degrades badly over time.

Men and Wild Horses uses the researches of Géricault’s first biographer, Charles Clément, to investigate the life of an artist whose bouts of depression and early death cut short a career that promised much but delivered less than the artist hoped. Clément, portrayed by Alan Dobie, informs us that Géricault only exhibited three paintings in the Paris Salon, none of which sold while the artist was alive. The largest of the three, The Raft of the Medusa, is recognised now as one of the great paintings of its age, but the Paris art world didn’t think so at the time. The story of the shipwreck survivors, and Géricault’s obsession with depicting their plight, forms the centrepiece of Megahey’s film which avoids too much awkward historical recreation. Géricault himself is only present via Clément’s account of his life, the memories of the artist’s friends, and the voiceover by Martin Jarvis which provides detail that the biographer was unable to find. The camerman for all three films in this series was Megahey’s regular collaborator, John Hooper, a real artist himself in his manipulation of light and shade. Men and Wild Horses is filled with many beautiful chiaroscuro compositions, so it’s a shame that the copy at YouTube isn’t better quality. The same account also has a copy of the Ingres film, Slaves of Fashion, while the David film, The Passing Show, may be seen here.

One of the “interviewees” in the film is Antoine Étex, the creator of Géricault’s monument in Père Lachaise cemetery. I took a few photos of this when I was there in 2006; it’s easier to stumble across than some of the other famous tombs, and includes among its details bronze reliefs of Géricault’s three major paintings. British readers will know that “gee-gee” is a colloquial term for a horse so there’s some wry amusement for les rosbifs in the sight of the letters surrounding the monument of a horse-obsessed painter. Despite snapping a close-up of the bronze Raft of the Medusa I was more interested in chasing Symbolist paintings in the Musée d’Orsay and the Gustave Moreau Museum so I didn’t go to look at the original in the Louvre. Maybe next time.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Complete Citizen Kane

• Schalcken the Painter revisited

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard