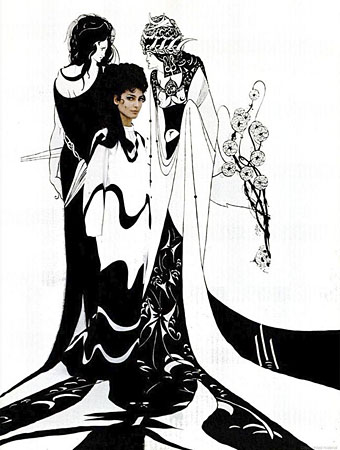

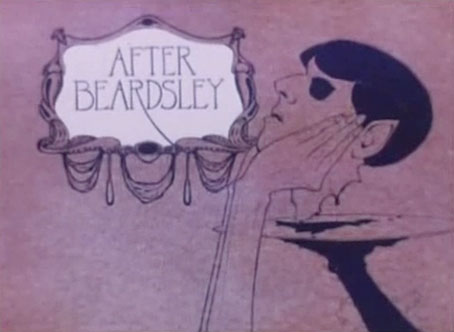

More of Aubrey Beardsley’s posthumous influence and more of the delightful collision between the 1890s and the 1960s. Monsieur Thombeau turned up this striking fashion shoot from LIFE magazine for 1967 showing a model posed against one of the Salomé drawings. A couple of days after this was posted, a reader wrote to point me to this list of films featuring Beardsley artwork. Most of those I knew about already but I certainly hadn’t heard of Death Bed: The Bed That Eats (1977), a low-budget horror film about which we’re told:

A large, black, four-poster bed, possessed by a demon, is passed from owner to owner. The demon was a tree, who became a breeze and seemingly fell in love with a woman he blew past. The demon then took human form and conjured up a bed. While he was making love with the woman she died and his eyes bled onto the bed, causing it to become possessed. Those who come into contact with the bed are frequently consumed by it (victims are pulled into what is apparently a large chamber of digestive fluids beneath the sheets). The bed demonstrates a malevolent intelligence as well as some psychokinetic and limited telepathic abilities to manipulate dreams. A running commentary or chorus is supplied by the ghost—if that is the correct word—of an artist (who would appear to be Aubrey Beardsley, though this is never stated directly) trapped behind a painting on the wall.

That’s a posthumous fame Aubrey never would have anticipated. If anyone has seen this, let us know what you thought.

Carry On Loving (1970).

Absent from the list of films is Ken Russell’s Salome’s Last Dance, which features the Salomé pictures again in its title sequence, and Carry On Loving, one of the dreadful British sex comedies which has an entire scene set in a modish pad decorated with Beardsley prints. Watch the scene in question here, if you must.

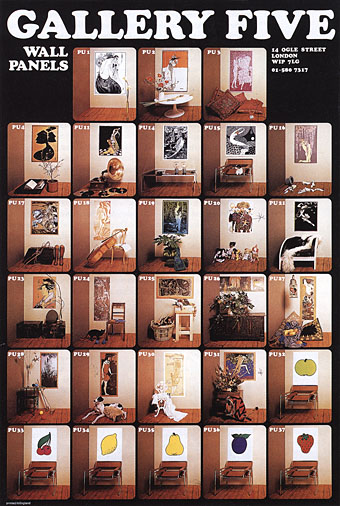

The prints were produced by a London company, Gallery Five, in the late 60s, and their ad shows they were also selling works by Kay Nielsen (seen in the Carry On clip), John Austen, Charles Ricketts, George Barbier, Jessie King and others. Gallery Five did much to popularise Beardsley’s art among people who might otherwise have never noticed his work, and their products turn up in many films and TV dramas of the period. Finally—although it’s by no means the last word on this subject—the V&A has two great Beardsley-derived ads for Elliott Boots by Paul Christodoulou here and here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive