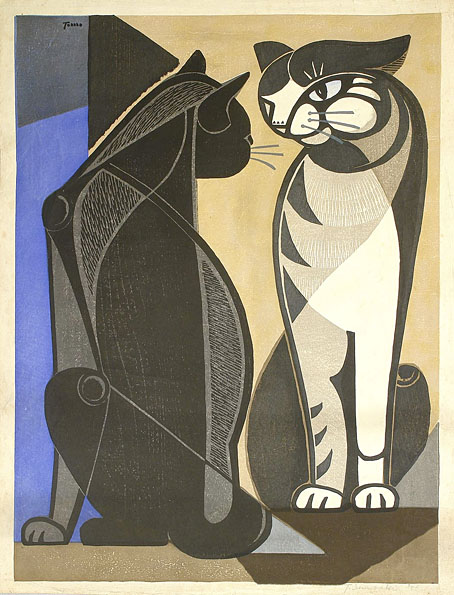

Chatting Cats (c.1960) by Tomoo Inagaki.

• New/old music: Follow The Light by Broadcast, a song which will appear on Spell Blanket—Collected Demos 2006–2009 in May. The album will be followed by another collection, Distant Call—Collected Demos 2000–2006, in September, with both releases being described as the last ever Broadcast albums. This was always going to happen eventually but I thought there might be a final collection of all the tracks the group recorded for compilations which have never been reissued.

• “Cats are all over Turkey. In Istanbul, which I visited before traveling to eastern Turkey, cats are welcome not just in cafes but in houses, restaurants, hotels, and bars.” Emily Sekine on the cats of Turkey.

• “El Shazly’s music is like a rush of new energy, a link between the past and present of Egyptian music that is fresh and vital.” Geeta Dayal on Egyptian singer and composer Nadah El Shazly.

• More werewolves: A trailer for Wulver’s Stane, a contemporary refashioning of werewolf lore. Director Joseph Cornelison is a reader of these pages. (Hi, Joseph!)

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Ghost Stories by EF Benson.

• At Colossal: Sacred geometries and scientific diagrams merge in the metaphysical world of Daniel Martin Diaz.

• At The Quietus: What does dying sound like? Jak Hutchcraft on music and the near-death experience.

• At Unquiet Things: Languid Dreams and Unsettling Poetry: The Art of Jason Mowry.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…Ronald Firbank Caprice (1917).

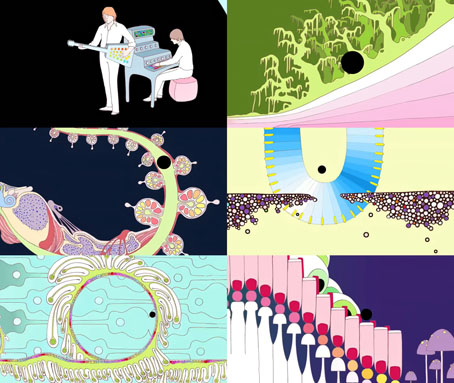

• Ashkasha, a short animated film by Lara Maltz.

• New music: Chimet by Mining.

• I’m The Wolf Man (1965) by Round Robin | The Werewolf (1972) by Barry Dransfield | Steppenwolf (1976) by Hawkwind