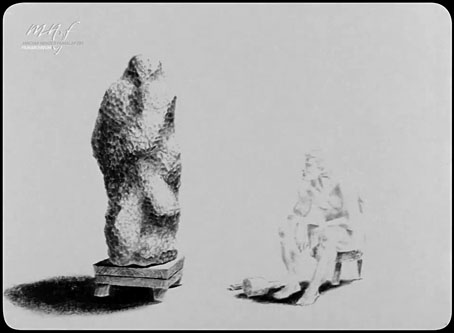

Sisyphus (1974).

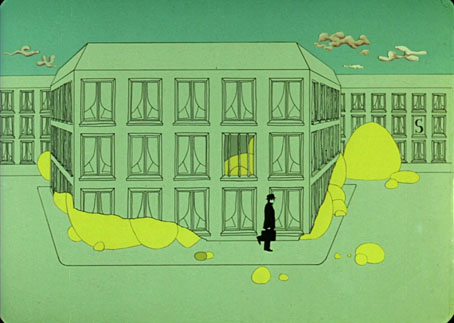

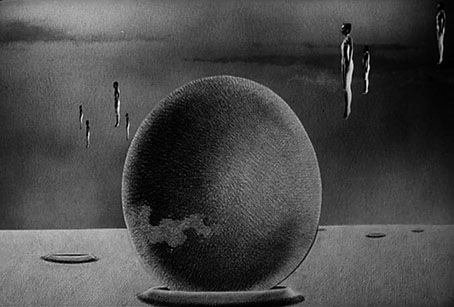

Hungarian animator Marcell Jankovics died in May last year but he lived just long enough to see his most celebrated feature, Son of the White Mare (1981), restored and released for the first time in the USA. The film—which I haven’t yet managed to see—is one of those that gets described as “most psychedelic ever”, a grand and rather unwise claim when other animated features such as Belladonna of Sadness (1973) and Paprika (2006) are very “psychedelic” in their own different ways (and both films I’d recommend, incidentally). Psychedelic or not, Son of the White Mare is beautifully styled and vividly coloured, to a degree that puts it at the polar extreme to these three shorts from Jankovics, all of which are exercises in hand-drawn, black-and-white minimalism.

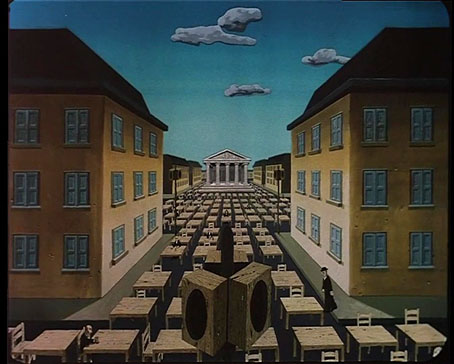

The Struggle (1977).

Hungarian animation from the Cold War era tends to be overshadowed by the films produced by the studios in Poland and the former Czechoslovakia, but animated films from all the Eastern Bloc nations were a fertile medium for symbolic expressions of frustration with the politics of the time. It’s a commonplace observation that repressive regimes inspire a flourishing of metaphor and symbolism in the arts. I don’t know whether Jankovics was being deliberately allegorical with these three shorts but when two of them concern familiar figures from Greek mythology you start to look for subtext. The films are all very brief but they’re also technically impressive. I especially like the way Sisyphus manages to convey a sense of colossal weight with nothing more than a few calligraphic flourishes.

Prometheus (1992).