Jerom photographed in a Jerome-studio fashion feature for Fantasticsmag.

Category: {fashion}

Fashion

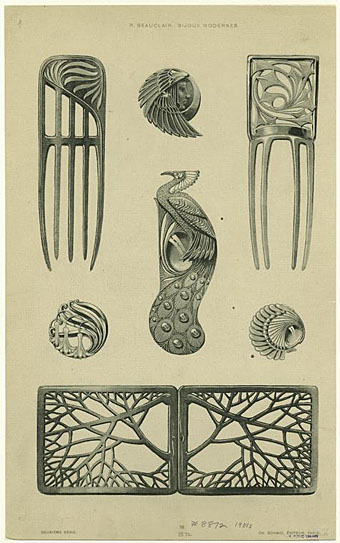

Rene Beauclair

Bijoux modernes (c. 1900) from a series of Art Nouveau designs by Rene Beauclair. As usual the peacock caught my attention on this page. There’s more by Beauclair at the NYPL Digital Gallery

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Elizabetes Iela 10b, Riga

• The Divine Sarah

• Whistler’s Peacock Room

• Lalique’s dragonflies

• Lucien Gaillard

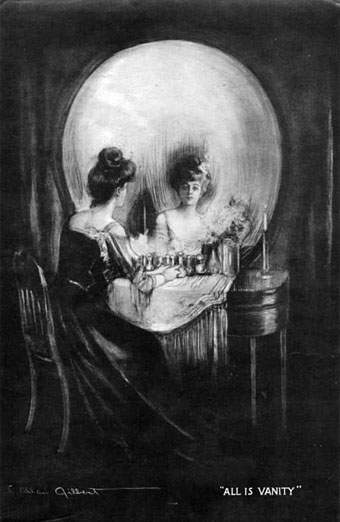

The skull beneath the skin

All Is Vanity by Charles Allan Gilbert (1892).

The subliminal skull is another of those perennial motifs that recur in art from time to time, and one which has become especially prevalent since the late 19th century. There seem to be a number of reasons for this, the most obvious being that if you’re going to show how clever you are by hiding one image inside another you may as well make the hidden thing something that everyone recognises. A secondary reason would seem to be the waning power of the vanitas theme. As painting became more pictorially sophisticated it wasn’t enough to simply show a skull and expect people to accept this with a stern moral as the principal content. Hence the development of death as a non-skeletal character in Symbolism and the reduction of skulls in pictures to a kind of playful game.

Holbein’s anamorphic skull in The Ambassadors is probably the grandfather of all the later versions but the more recent popularity of the hidden motif can be traced back to Charles Allan Gilbert whose 1892 picture, All is Vanity, drawn when he was just 18, was sold to Life Publishing in 1902, and subsequently spread all over the world in postcard form. Despite giving birth to a host of imitators, Gilbert’s picture is the one that still inspires artists and photographers up to the present day.

The Divine Sarah

Sarah Bernhardt by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1895).

You can’t be a fin de siècle fetishist and not develop a fascination with actress Sarah Bernhardt, a woman who was muse to many of the era’s finest artists, most notably Alphonse Mucha, who she employed as her official designer. Mucha’s marvellous posters are endlessly popular, of course; less well-known is the sculpture by academic painter and Orientalist Jean-Léon Gérôme, a rare three-dimensional work inspired by the actress.

Inkwell by Sarah Bernhardt (1880).

Even less well-known is Ms Bernhardt’s own design for a curious bat-winged inkwell. I’ve read of her having created other sculptural works but so far this is the only one I’ve seen a picture of. With something as decadent as this you’d really have to use peacock quills for pens, wouldn’t you?

Bracelet by Alphonse Mucha & Georges Fouquet (1899).

And in a similar sinister vein to the inkwell there’s this serpentine bracelet and ring, a superb one-off, designed by Mucha and crafted by the jeweller Fouquet. After seeing works such as this and the Lalique dragonfly (which Ms Bernhardt once wore), most other jewellery seems timid and unadventurous in comparison.

Update: Added another photo of the inkwell.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Philippe Wolfers, 1858–1929

• Lalique’s dragonflies

• Lucien Gaillard

• Smoke

• The Masks of Medusa

The art of Philippe Wolfers, 1858–1929

Maléficia (1905).

Much of the jewellery and sculpture produced by Phillipe Wolfers demonstrates the tendency of Art Nouveau and decorative Symbolism to evolve from Decadence to full-blown Gothic. The sinister recurs in Wolfers’ creations whether in the form of baleful females such as Malèficia and his Medusa pendant, or in the shape of bats, insects and the ubiquitous fin de siècle serpent. There’s more Wolfers on the web than there was a couple of years ago but still too little; I scanned Malèficia from a book and swiped the bat brooch belt buckle (also a book scan) from Beautiful Century.

Large dragonfly (1903–04).

Le Jour et la Nuit (1897).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Lalique’s dragonflies

• Lucien Gaillard

• The Masks of Medusa