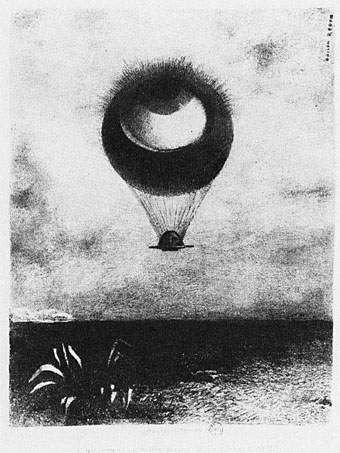

L’Oeil, comme un ballon bizarre se dirige vers l’infini from A Edgar Poe (1882).

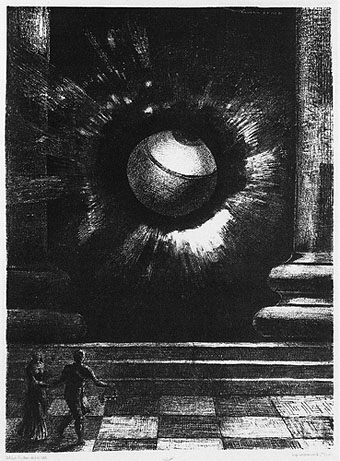

Another decently thorough Symbolist website covers the life and work of Odilon Redon (1840–1916), an artist whose pastels and prints were strange even by the standards of his contemporaries. His giant eyeballs and other floating figures are always startling and point the way inevitably to Surrealism, especially in dream lithographs like the one below.

Vision from Dans le Rêve (1879).

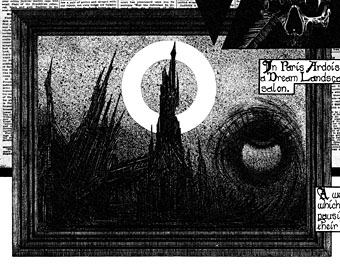

I compounded that Symbolist/Surrealist association when I was drawing The Call of Cthulhu in 1987 by showing Ardois-Boonot’s Dream Landscape (which Lovecraft doesn’t describe beyond the word “blasphemous”) as being a Max Ernst-style frottage canvas with a Redon eye rising from the murk. Cthulhu’s presence reduced to a single ocular motif like the eye of Sauron.

The Call of Cthulhu (1988).

And while we’re on the subject there’s Guy Maddin’s typically phantasmic short, Odilon Redon or The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity made for the BBC in 1995. Ostensibly based on the balloon picture above, this manages to reference a host of other Redon lithographs and charcoal drawings in the space of four-and-a-half minutes. Sublimely weird and weirdly sublime.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Arthur Zaidenberg’s À Rebours

• The Heart of the World