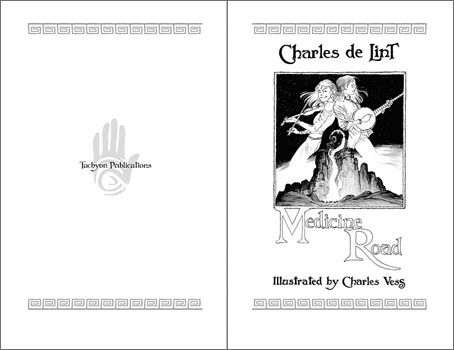

The second of my book designs for Tachyon Publications is published this month and it was good to receive a copy in the same week as getting a load of new CDs. Medicine Road is a contemporary fantasy of shape-shifting and shamanic magic set in the American South West. This job was particularly pleasurable for being illustrated by Charles Vess, celebrated among other things for his many collaborations with Neil Gaiman, including Stardust. I embellished the opening pages with designs based on Native American petroglyphs, a couple of which are from the tribes mentioned in the text.

Laurel and Bess Dillard are charismatic bluegrass musicians enjoying the success of their first Southwestern tour. But the Dillard girls know that magical adventures are always at hand. Upon meeting two mysterious strangers at a gig, the red-headed twins are drawn into a age-old, mystical wager along the Medicine Road.

One day, seeing a red dog chasing a jackalope, Coyote Woman gave them human forms. They became Jim Changing Dog and Alice Corn Hair. In return, both of them must find true love within a hundred years or their “five-fingered” forms will be forfeit. Alice has found her soul mate, but trickster Jim is unwilling to settle down — until he sets eyes upon free-spirited Bess Dillard.

Yet time is running out for the red dog and the jackalope. In just two weeks they will journey to their reckoning at the Medicine Wheel. Meanwhile, a motorcycle-riding seductress and a vengeful rattlesnake woman are eager to meddle, and Bess and Laurel, caught in a web of love and lies, must find their own paths into the spirit world.

Next up from Tachyon will be a book by Kage Baker. More about that later.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Best of Michael Moorcock