The Obscure World.

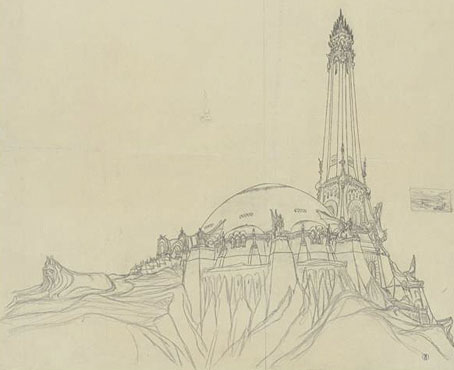

Les Murailles de Samaris (1983) by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters is the first of the stories which explores the world of Les Cités Obscures, a “counter-Earth” on the opposite side of our Sun with a continent of separate city-states, each with their own distinct architectural style. Having discovered these stories first in their French editions it wasn’t immediately apparent how much the Obscure World was supposed to be connected to our own; a number of the books contain references to people or places in our world, while the city of Brüsel, subject of the book of that name, is a kind of parallel Brussels. The counter-Earth explanation isn’t given in the early books but seems to have evolved later, as does Schuiten and Peeters’ introduction of portals between the worlds which imply a two-way leakage of influence. Writer and artist encourage readers of the series to suggest or “discover” new portals to the Obscure World.

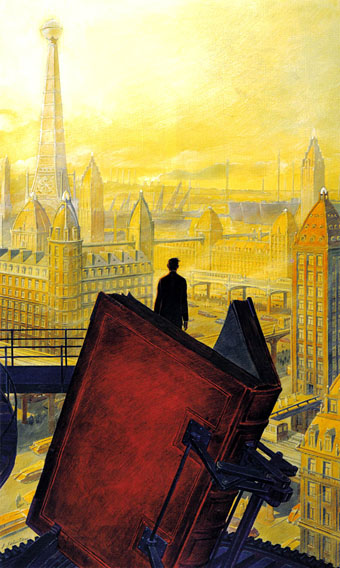

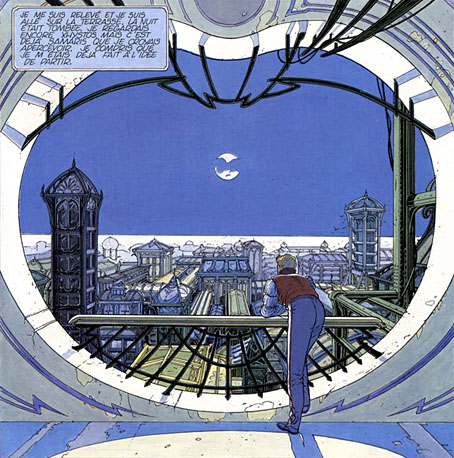

A view over Xhystos.

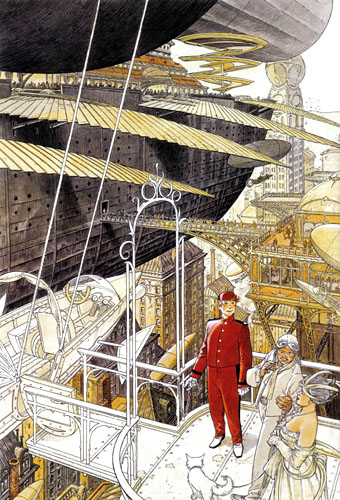

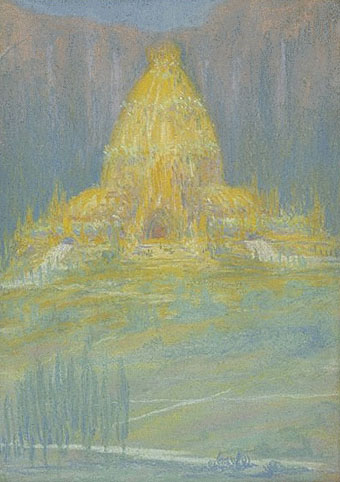

The distant city of Samaris is the mysterious destination of Les Murailles de Samaris (The Walls of Samaris). The story begins in the city of Xhystos whose style is fully Art Nouveau in a manner reminiscent of the celebrated Belgian architect Victor Horta, if Horta had been allowed to design a city where every building is decorated with wrought-iron curves and glass-canopied roofs, and where trams go by on elevated roads several storeys high. The narrator, Franz, is informed by the city authorities that he’s been chosen to go on a perilous mission to discover whether rumours about the nature of Samaris are true or not. Previous explorers have failed to return so Franz’s friends and girlfriend regard his acceptance of the mission as suicidal. What follows is a journey by steam train out of the city into a surrounding zone of lawless ruins, then a journey by “altiplane” and “aerophele”, the latter being a kind of multi-winged sand yacht.

Continue reading “Les Murailles de Samaris by Schuiten & Peeters”