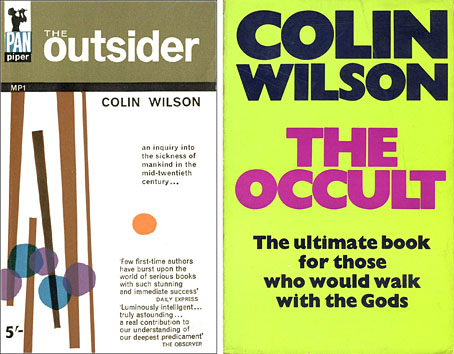

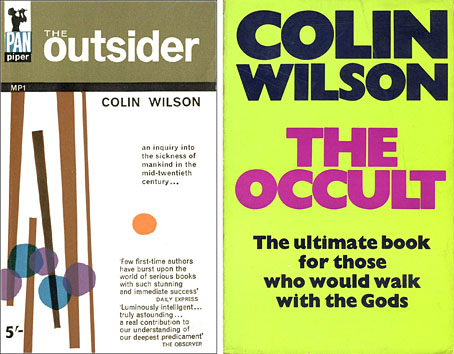

The Outsider (1956), 1963 edition; The Occult (1971), 1973 edition.

The cover of the 1973 UK paperback of Colin Wilson‘s mammoth overview of occultism can still be offered as a pinnacle of hyperbole. The book itself is a very serious and informative study but its success set Wilson on a path as a writer about the paranormal where he’d previously been concerned with literature, philosophy and psychology. For many critics this finished his already shaky reputation as a serious thinker. He continued to write about philosophy and literature in subsequent books but dubious speculations about Atlantis are always more commercially attractive than studies of Nietzsche, hence the proliferation of lost continents in the later part of a bibliography which the Wilson website lists at 114 titles. Wilson was a maverick intellectual whose curiosity ignored many of the boundaries that restrained his metropolitan contemporaries; he was also an autodidact of a type that seems to irritate the university-educated. Mentions of his name in British newspapers were frequently couched in sneering or dismissive terms. His current reputation can be measured by the lack of attention the news of his death has prompted in the UK at the time of writing. (That said, dying on the same day as Nelson Mandela was unfortunate timing.)

Savoy Books published an edition of Wilson’s crime novel, The Killer, in 2002. I designed that volume, rather badly, I think. In 2004 Robert Meadley wrote a book-length reaction to Wilson’s autobiography, Dreaming to Some Purpose, which can be downloaded for free from Savoy. In it Meadley mounts a robust defence of Wilson against the broadsheet termagants. Elsewhere: the only newspaper obituary so far is at The Times (subscription required); Colin Wilson on Desert Island Discs in 1978; Gary Lachman interviewing Wilson for Fortean Times in 2004; musician Anthony Reynolds discussing his collaboration with Wilson.

• “Art, music and a mind-blowing voyage of discovery”: Richard Neville on the late Martin Sharp. At Design Observer Rick Poynor looks back at Sharp’s book and magazine illustrations of the 1960s. Of particular note is Sharp’s contribution to the “Magic Theatre” issue of Oz magazine, a unique combination of collaged visuals and text which Alan Moore often refers to as a favourite work. (See issue 12 of Moore’s Promethea, “The Magic Theatre of the Mind“.)

• “The naked woman in art isn’t unusual, but we have trouble viewing the male body as a sexual, or artistic, object,” says James Polchin.

But how can anyone be bored when there’s always death to think about? Every day. Every hour. Don’t you? All the rest is just evading or glossing the real subject of our lives. Beckett, again, the maestro of death: Never but the one matter. The dead and gone. The dying and the going. From the word go. I too shall cease and be as when I was not yet, only all over instead of in store.

Jenny Diski on death and dying.

• A teaser trailer for The Dreamlands, a film by Huan Vu (Die Farbe) based on HP Lovecraft’s Dream Cycle.

• “On Watching Wages of Fear with my 11-Year-Old Daughter” by Debra Morris.

• Abram Games’ “bat wings” BBC logo is 60 years old. See it in action here.

• At Strange Flowers: Romaine Brooks‘ portraits of her famous friends.

• At Front Free Endpaper: Mervyn Peake illustrates Treasure Island.

• The Great God Pan (plus satyrs and fauns) at Pinterest.

• Dan Wilson on “Electric Music” on the Victorian stage.

• Mix of the week: Fact Mix 414 by Julianna Barwick.

• The BFI chooses 10 great British rural horror films.

• Dunwich – The search for Britain’s Atlantis.

• The Grand Canyon filled with fog.

• The Bells of Dunwich (1975) by Stone Angel | O.O.B.E. (1992) by The Orb (feat. Colin Wilson) | Why We Make It Difficult On Ourselves (2010) by Anthony Reynolds & Colin Wilson