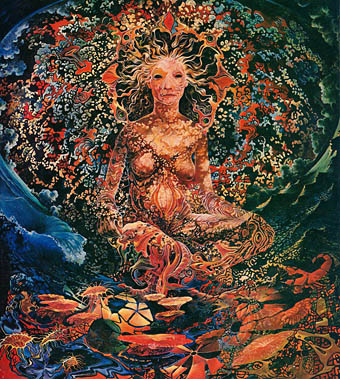

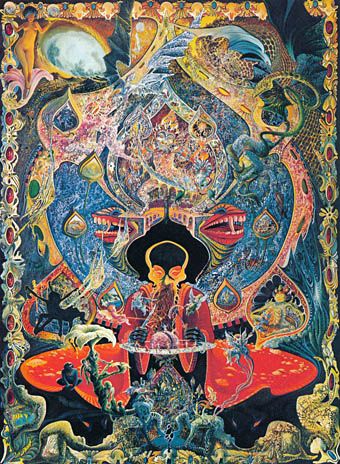

Manifold (2015), a painting by Samantha Keely Smith which will appear in April on the cover of Life Metal, a new album by Sunn O))).

• At Expanding Mind: Professor and queer historian Heather Lukes talks with Erik Davis about Silver Lake riots, gay bikers, house ball scenes, the nostalgia for repression, and the joys and challenges of working on the online archive The Grit and Glamour of Queer LA Subculture.

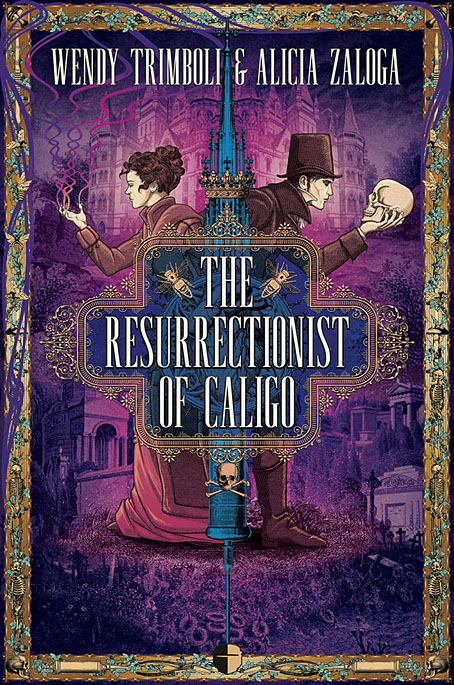

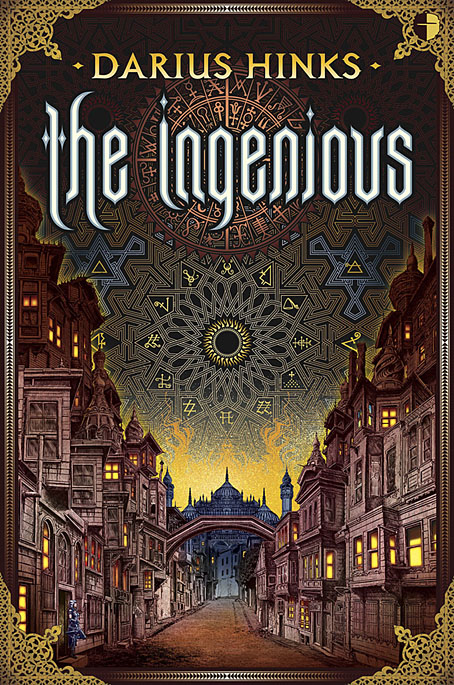

• A Stroke of Ingenious: Chatting Fear and Fantasy with Darius Hinks. Also this week, Darius Hinks’ The Ingenious (for which I created the cover art) was featured in a Barnes & Noble list of seven attractive (if hazardous) fantastic cities.

• “From the late ’60s and through the ’70s broadcasters invested in home-grown kids’ television, and much of it was decidedly weird.” Paul Walsh on the vanished, thought-provoking strangeness of British TV.

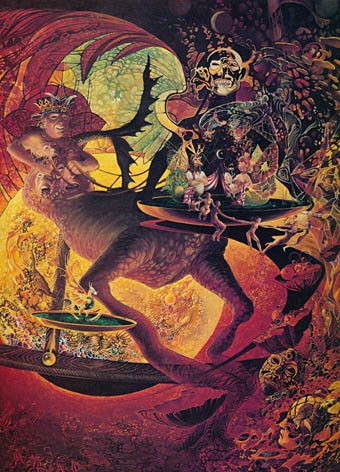

That late surrealism still needs rescuing by curators and critics is perhaps not a sign of its defeat but of the breadth and pervasiveness of its triumph. Could we have Pablo Picasso or Jackson Pollock without surrealism? What about David Lynch, JG Ballard or Angela Carter? As an influence, it’s easy to give [Dorothy Tanning] a crucial place in the canon of feminist art. Louise Bourgeois was born just a year later than Tanning but only started to sew after Tanning had exhibited her first sculptures.

Lara Fiegel on the weird, wild world of Dorothea Tanning

• After its own death / Walking in a spiral towards the house by Nivhek, a new album from Liz Harris (Grouper) “recorded using Mellotron, guitar, field recordings, tapes, and broken FX pedals”.

• At Dangerous Minds: Michael Rother (Neu!/Harmonia) on the forthcoming reissue of his solo albums from the 1970s.

• Clesse by Clesse, another pseudonymous musical project by Jon Brooks (The Advisory Council et al).

• After Dark: The art of life at night—and in new lights by Francine Prose.

• Elena Lazic on where to begin with Gaspar Noé.

• Mix of the week: Headlands by David Colohan.

• Steven Heller‘s confessions of a letterhead.

• RIP Albert Finney.

• Void (2009) by Monolake | Void (2013) by Emptyset | Void (2014) by The Bug feat. Liz Harris