“But it is a curve each of them feels, unmistakably. It is the parabola. They must have guessed, once or twice—guessed and refused to believe—that everything, always, collectively, had been moving toward that purified shape latent in the sky, that shape of no surprise, no second chances, no return. Yet they do move forever under it, reserved for its own black-and-white bad news certainly as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children….”

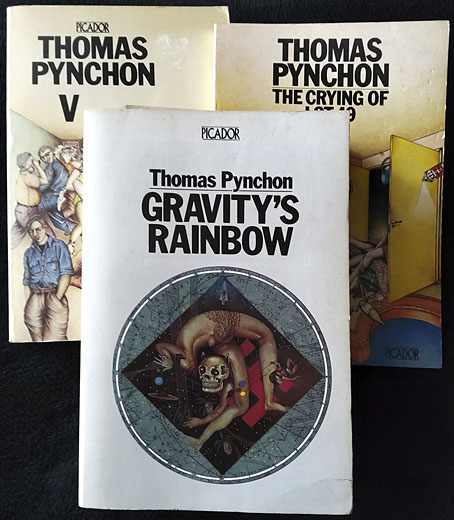

Reader, I read it. It isn’t an admission of great achievement to announce that you’ve reached the last page of a novel after a handful of stalled attempts, but when it’s taken me 36 years to reach this point it feels worthy of note; and besides which, Gravity’s Rainbow isn’t an ordinary novel. Umberto Eco is partly responsible for my return to Pynchon. I’d just finished The Name of the Rose, a book I’d avoided for years even while reading (and enjoying) a couple of Eco’s other novels, and was wondering what to read next. Maybe it was time to try the Rocket book again? The thick white spine of the Picador edition—760 pages in 10pt type—would accuse me every time I spotted it on the shelf: “Still haven’t made it to page 100, have you?” For many people this happens with novels because a book is “difficult” (which I didn’t think it was), or boring (which it isn’t at all), or simply too long (page count doesn’t put me off). Back in 1985 I was looking for more heavyweight fare after reading Ulysses, something I’ve now done several times, so I wasn’t going to be intimidated by a novel which is misleadingly compared to Ulysses on its back cover. If anything the comparison was an enticing one. Pynchon at the time exerted a gravitational pull (so to speak) for being very mysterious, although this was a decade when most living authors, especially foreign ones, were mysterious to a greater degree than they are today, when so many have their own websites and social media profiles. Pynchon’s works were also referred to in interesting places, unlike his less mysterious contemporaries. I may be misremembering but I seem to recall a mention of the W.A.S.T.E. enigma from The Crying of Lot 49 in Robert Shea & Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus!; if it is there then it’s no surprise that a writer so preoccupied with conspiracy and paranoia would find favour with the authors of the ultimate conspiracy novel. (And that’s not all. I’m surprised now by the amount of coincidental correspondence between Illuminatus! and Gravity’s Rainbow. Both novels were being written at the same time, the late 1960s, yet both refer to the Illuminati, the eye in the pyramid on the dollar bill, Nazi occultism, and the death of John Dillinger. Both novels also acknowledge the precedent of Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, another remarkable conflation of conspiracy, secret history, and wild invention.)

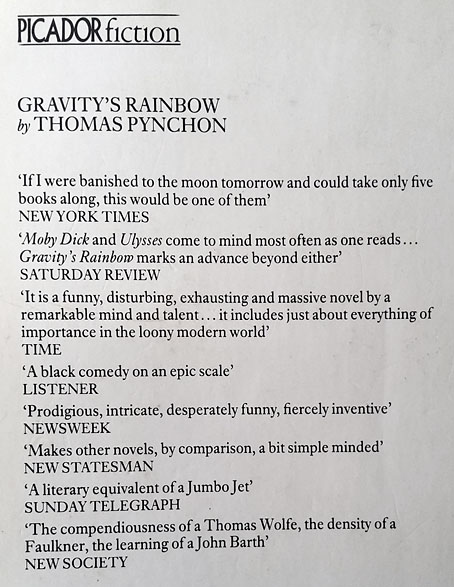

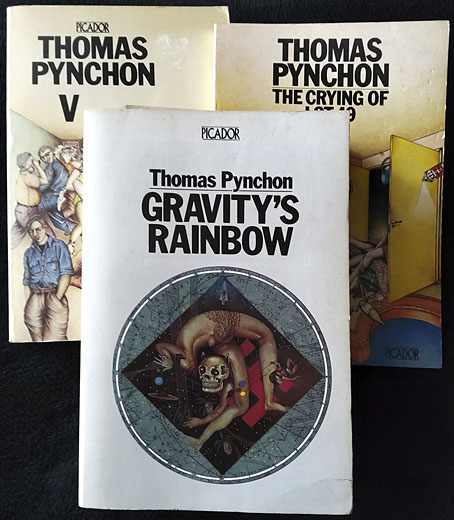

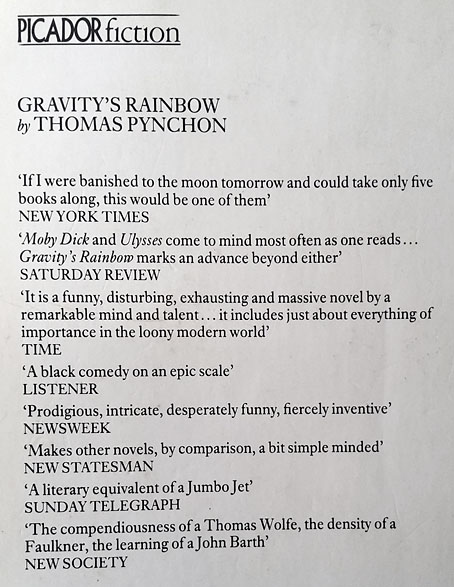

Pynchon had other connections to the kind of fiction I was already interested in. One of his early short stories, Entropy, had been published in New Worlds magazine in 1969, although editor Michael Moorcock later claimed to have avoided reading any of the novels until much later. And, Pynchon, like Shea & Wilson (and Moorcock…), made pop-culture waves. I think it was Laurie Anderson who put Gravity’s Rainbow in the centre of my radar when she released Mister Heartbreak, an album whose third song, Gravity’s Angel, refers to the novel and is dedicated to its author. As for the novel itself, in the mid-1980s this was still Pynchon’s major work, the one that fully established his reputation. Nothing new had appeared since its publication in 1973; Vineland, and the subsequent acceleration of the authorial production line, was six years away. The final lure was the refusal of the Picador edition to communicate very much of its contents: what was this thick volume actually about? The back cover is filled with praise but doesn’t tell you anything about the novel at all, while the cover illustration by Anita Kunz suggests a scenario connected with the Second World War but little else. (“This was one of the most complicated books I ever read,” says the artist, “and really hard to get the germ of the idea. Pynchon kept going off in tangents. I mixed up the art the same way the writer did and made an image that can be read in all directions.”) It’s only when you start reading the book that you find the connection between the novel’s dominant concerns—the development of the V-2 rockets used by the Nazis to bomb London, and the erotic compulsions of Tyrone Slothrop, an American lieutenant at large in war-ravaged Europe—subtly reflected in the illustration, much more subtly than the cover art on the edition that preceded this one.

Continue reading “Going beyond the zero”