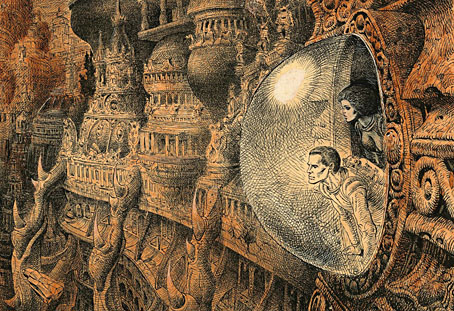

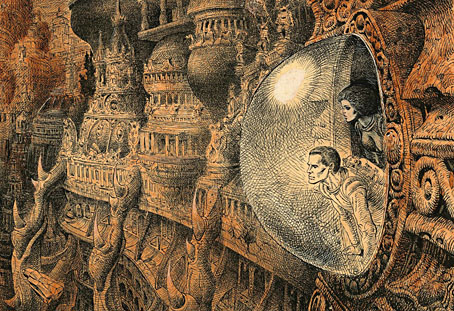

Illustration by Moebius for Les Robinsons du Cosmos (1970) by Francis Carsac.

• Notre Dame des Fleurs is a collection of art based on or inspired by the Jean Genet novel. The book, which includes some new work of mine, will be published in February. Editor Jan van Rijn has a trailer for it here. It’s limited to 150 copies so anyone interested is advised to pre-order.

• Books that made me: William Gibson‘s influential reading. Good to see him mention Suttree by Cormac McCarthy, an outstanding novel that might be better known if it wasn’t for the gravitational pull of McCarthy’s other works.

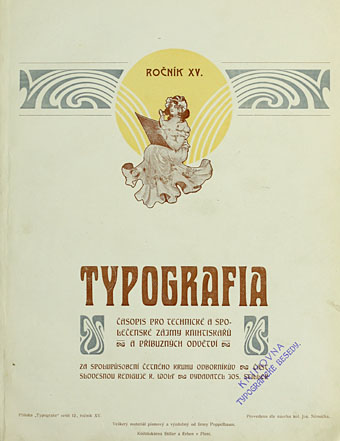

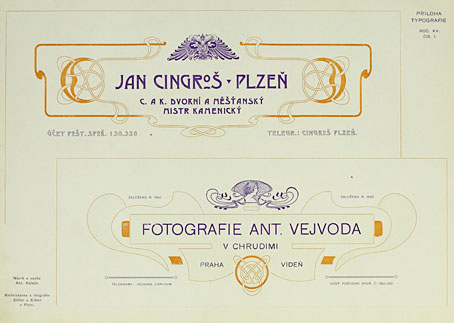

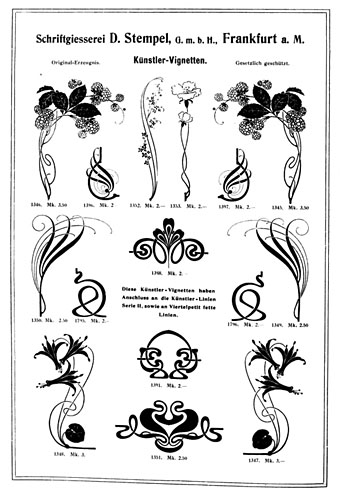

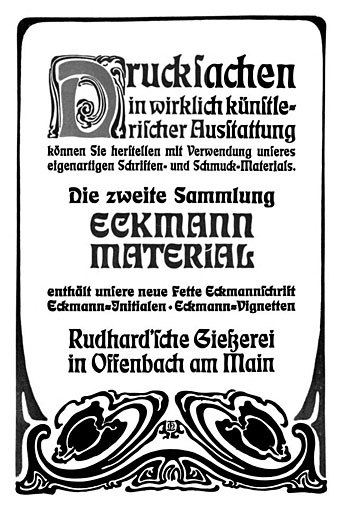

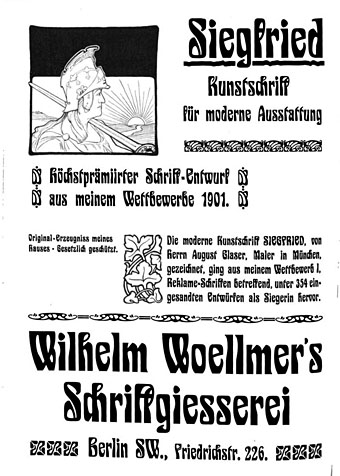

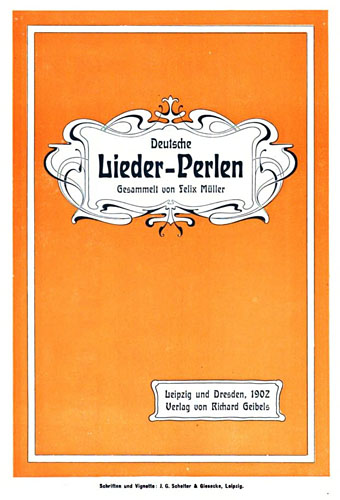

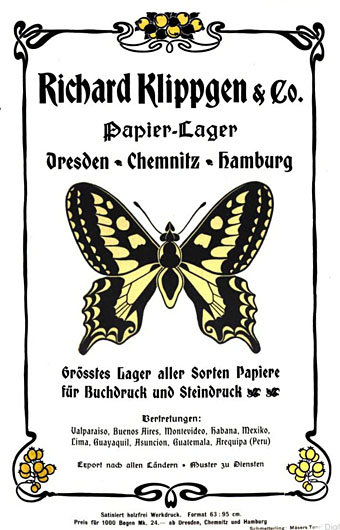

• Zagava have announced a paperback reprint of The Art of Ilna Ewers-Wunderwald, a collection of neglected Art Nouveau drawings and designs compiled by Sven Brömsel.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Black_Acrylic presents…He Stood In The Bath And He Stamped On The Floor: A Joe Meek Day.

• More yearly roundups: Our Haunted Year 2020 by Swan River Press, and The Year That Never Was by blissblog.

• New music: Spaceman Mystery Of The Terror Triangle by The Night Monitor.

• Ralph Steadman’s guided tour through six decades of irrepressible art.

• At Greydogtales: Valentine Dyall: Mystery and Mesmerism.

• At Wormwoodiana: The Esoteric in Britain, 1921.

• At Strange Flowers: Marie Menken’s Lights.

• I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight (1974) by Richard and Linda Thompson | Neon Lights (1978) by Kraftwerk | Lights (1980) by Metabolist